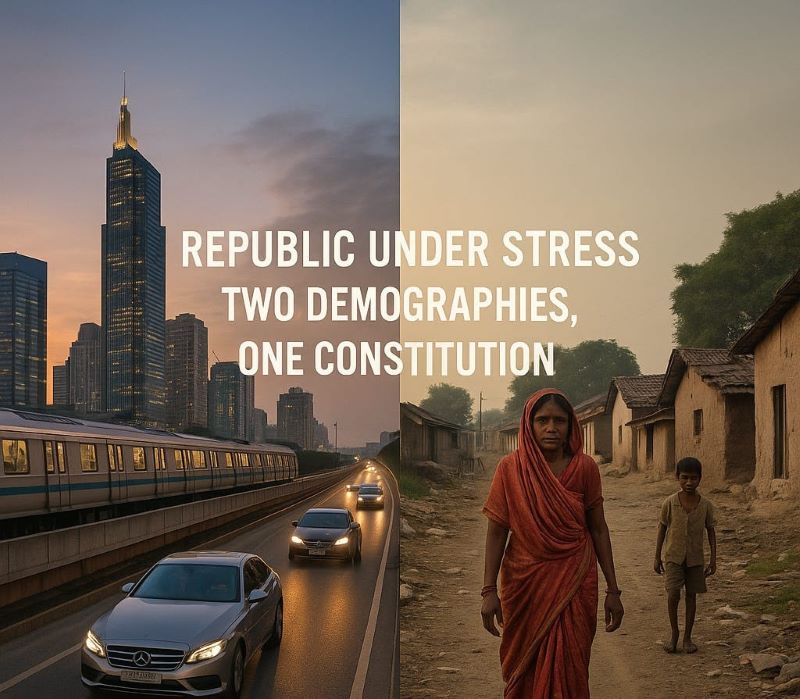

The cliché is familiar: one India of gleaming airports, metros, and IT hubs; another of villages, hunger and tribal hamlets. But the real fault line runs deeper. It is not only in infrastructure or literacy, but in how policies are designed. For decades, governments have nurtured two demographies: one cushioned into global mobility and capital comfort, the other tethered to patriotism, rations and sacrifice.

The cliché is familiar: one India of gleaming airports, metros, and IT hubs; another of villages, hunger and tribal hamlets. But the real fault line runs deeper. It is not only in infrastructure or literacy, but in how policies are designed. For decades, governments have nurtured two demographies: one cushioned into global mobility and capital comfort, the other tethered to patriotism, rations and sacrifice.

Since independence, the Republic’s vocabulary has been steeped in commemoration—freedom fighters, saffron sacrifice, the cry of Inquilab Zindabad. We all love the tricolour, and Har Ghar Tiranga shows it. Children waving flags on national days embody real pride. But the symbolism is largely directed at Bharat: farmers, workers, and the lower middle class. The elite need no such appeals; policy itself secures their prosperity.

The Patriotism Premium

For most citizens, patriotism is not rhetoric—it is lived experience. They fill the ranks of the armed forces, pay rising indirect taxes, and queue at ration shops. The state proudly declares that 80 crore Indians get free foodgrain, presenting permanent dependence as a triumph of governance.

Meanwhile, the middle class pays GST and income tax in equal measure. They are told their sacrifice keeps the Republic strong, even as their Achhe Din (अच्छे दिन) remain a mirage. The emotional burden of nationalism—waving flags, singing anthems, attending parades—is carried by Bharat, while policy writes different rules for India.

Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan

Shastri ji’s call—“Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan”—once embodied balance. It honoured the soldier at the border and the farmer in the field. Today, the slogan is repeated at rallies and parades, but has drifted into ritual. The jawan is feted in commemorations yet many veterans and widows battle for fair pensions. The kisan is hailed as annadata but often earns less than a daily-wage worker in Chandigarh.

In spirit, Shastri’s words should have anchored national priorities. In practice, they have become rhetoric for Bharat, while actual policy pivots to growth targets, global capital and corporate incentives.Religious festivals and centennial commemorations show the same divide. Millions of ordinary citizens throng yatras and anniversaries, often risking their lives in stampedes just to glimpse the sacred. For them, faith is collective, costly, and crowded.

Karan Bir Singh Sidhu, IAS (Retd.), former Special Chief Secretary, Punjab, writes on the intersection of constitutional probity, due process, and democratic supremacy.

The elite experience a different reality: the VVIP darshan. The politically connected and the wealthy are whisked past queues, assured safety, and guaranteed access. Once again, the Republic uses symbolism and mass participation to engage Bharat, while access and privilege flow quietly to India.

Global Citizens, Rooted Subjects

Policy has actively opened doors for the wealthy. Corporations can invest abroad up to 400 per cent of net worth under the automatic route. Individuals remitting money abroad face a 20 per cent tax at source unless the purpose is narrowly exempt. The signal is clear: corporate capital is welcome to roam free; middle-class aspirations are taxed at the border.

India is also one of the few countries where the maximum personal income tax rate is significantly higher than the corporate tax rate. A salaried individual at the top bracket can pay nearly 39 per cent after surcharge and cess, while corporations enjoy a base rate of just 22 per cent—and in some cases 15 per cent. This inversion of global norms tilts the scales further: the professional and middle-class taxpayer bears a heavier load, while incorporated capital enjoys lighter treatment.

The wealthy buy residencies overseas, acquire foreign properties, and hedge loyalties with ease. They are not asked to wave flags or march in rallies. Bharat, meanwhile, remains rooted to ration shops and farm plots, reminded of sacrifice through symbolism rather than secured by policy.

Migrant Labour as the Hidden Spine

The Republic’s growth rests on migrant labour. Bihar, UP, Odisha, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh supply workers to Gujarat’s textile mills, Tamil Nadu’s knitwear factories, and Punjab’s paddy fields. They power “India,” but live as “Bharat.”

On national holidays they too wave flags, chant Inquilab Zindabad, and join patriotic displays. But when the parades are over, they return to cramped tenements and insecure jobs. Har Ghar Tiranga gives them pride for a day; policy leaves them invisible the rest of the year.

The Farmer’s Arithmetic

The myth of the wealthy farmer still persists. Yet surveys show the average farm household earns little more than an unskilled daily-wage worker in Chandigarh. A cultivator with two acres is often worse off than a labourer.

Farmers are showered with patriotic imagery—Jai Kisan, annadata, saffron fields in posters—but little else. MSP is an announcement, not a right. Export bans and sudden import relaxations crash farm-gate prices. Fertiliser is subsidised on paper but often scarce in practice. Farmers are commemorated but not protected, invoked in rhetoric but excluded from prosperity.

Growth Without Equity

The Republic’s vocabulary today is saturated with growth, efficiency, global competitiveness. We hear of a US$40-trillion economy by 2047, of becoming a Vishwaguru. But equity is missing from the triad. The one per cent flourishes, stock markets boom, but inequality deepens.

The Republic celebrates national days with flag-waving, chants of Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan, and memories of revolutionaries. But these commemorations are not meant for the uber-rich. Their loyalty lies in capital mobility and overseas residencies. Bharat carries the symbolism and the sacrifice; India carries the privilege.

Mirage of Achhe Din (अच्छे दिन)

For the uber-rich, Achhe Din (अच्छे दिन) have already arrived. Lower corporate tax rates, global opportunities, residencies abroad—the good days are real and tangible. For the rest, Achhe Din (अच्छे दिन) remain a shimmering mirage; the reality is more akin to ache and din. The poor survive on subsidies, the middle class shoulders the tax burden, and farmers live with shrinking margins.

They are offered Har Ghar Tiranga, saffron rallies, sacred festivals, and slogans of sacrifice. India gets comfort; Bharat gets commemoration.

Centenary: Independence in 2047, Republic in 2050

By 2047, India will mark 100 years of independence. By 2050, it will complete 100 years as a Republic. The choice is stark: will we be one nation of shared opportunity, or two demographies—one island of global elites, another of welfare-dependent masses, with a strained middle between them?

This is not about secession; it is about estrangement. If slogans like Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan, campaigns like Har Ghar Tiranga, and festivals of saffron sacrifice remain targeted only at Bharat while policy continues to serve India, the Republic’s stress lines will deepen.

The Way Forward

The challenge is not partisan. Successive governments have relied on symbols to bind Bharat, while shaping policy to benefit India. What is needed is balance:

Housing, healthcare and portability for migrant workers.

Predictable procurement and income-risk tools for farmers.

Tax design that does not squeeze the middle while sparing the elite.

Welfare measured not by ration dependence but by mobility and opportunity.

Beyond Government

The responsibility cannot rest on the state alone. Civil society, industry, unions, and citizens must insist that slogans match substance. Only then will Har Ghar Tiranga, Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan, saffron sacrifice, and Inquilab Zindabad be more than symbolism.

The Republic will grow. That is certain. But will it still belong equally to all its people when it turns 100? That is the question.