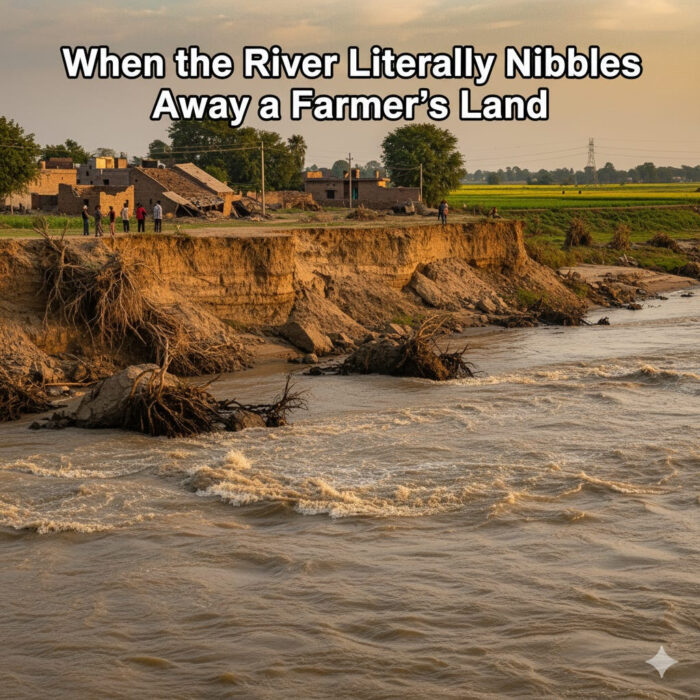

This year’s floods were not just water and headlines. Along the Ravi, the shock was cartographic: dhussi bandhs gave way, fresh creeks sliced through fields, and whole parcels of land seemed to melt into the current. For many farmers in Gurdaspur, Amritsar, and Pathankot, this wasn’t merely “crop damage.” It was cadastral loss—khasra numbers swallowed and boundaries blurred—followed, in some places, by new silted land appearing elsewhere.

This year’s floods were not just water and headlines. Along the Ravi, the shock was cartographic: dhussi bandhs gave way, fresh creeks sliced through fields, and whole parcels of land seemed to melt into the current. For many farmers in Gurdaspur, Amritsar, and Pathankot, this wasn’t merely “crop damage.” It was cadastral loss—khasra numbers swallowed and boundaries blurred—followed, in some places, by new silted land appearing elsewhere.

This was a reminder that in Punjab, the river does not merely flood fields; it rearranges ownership itself.

The Ravi’s special complication: one bank lies across the border

On much of its Punjab run, the Ravi is a transboundary river. The right (western) bank is generally in Pakistan; India mostly holds the left bank, although a few Indian villages lie “us-paar” (across the Ravi), particularly in Dhar Kalan tehsil of Pathankot.

This makes land loss to the Ravi unusually final. When the eastern (Indian) bank shifts inward, eating away the landholder’s fields, the loss is practically permanent—because the soil has gone toward or beyond the international line. A farmer cannot reclaim across the border, and Indian revenue authorities cannot record recovery on the opposite bank.

That stark reality makes timely survey and record work on the Indian side all the more crucial.

How the British turned floods into law

The British understood early on that rivers could wreck revenue. From Plassey (1757) to the Annexation of Punjab (1849), the Raj’s land-revenue state had to answer a basic question: when a river eats or yields land, who owns it?

Bengal got the first codification with Regulation XI of 1825 on alluvion (gain) and diluvion (loss). Punjab eventually received its own law: the Punjab Land Revenue Act, 1887 (PLRA). In 1899, special provisions were added (sections 101-A to 101-F) to deal with shifting river boundaries.

The ICS officers—Collectors, Settlement Officers, and Financial Commissioners—built manuals to carry this into the field: the Punjab Land Administration Manual and the Punjab Settlement Manual. These volumes did more than theorise; they taught patwaris, kanungoes and tehsildars/ naib tehsildars how to walk riverbanks, triangulate shifts, and write burdi (lost land) and baramadi (recovered land) into the record.

The layperson’s rule of thumb: land follows the river

The manuals set out a simple principle: land follows the river.

Diluvion (burdi): If your land is gradually eroded, you lose it.

Alluvion (baramadi): If the river leaves fresh silted soil, that land belongs to the estate it attaches to.

But the law also added fairness. When authorities fix a permanent boundary, ownership should follow that line—except where the land is under cultivation or clearly valuable. In that case, the Collector must pause the transfer of rights, so farmers are not uprooted overnight.

The Collector’s pen is the real boundary

The Punjab Land Revenue Act, 1887 allows the State to order a permanent boundary between riverain estates, with the Collector drawing the line “justly and equitably” under Financial Commissioner oversight.

Once that line is fixed, rights don’t swing with every meander. If the line would instantly strip cultivated land from a farmer, s.101-B requires suspension of the transfer. And if someone wants certainty now, s.101-C allows immediate transfer—but only against compensation, calculated under Land Acquisition Act principles.

In short: a good map and a good order are worth more than a sandbag.

Records first: how burdi and baramadi become law

After a flood, the first step is not relief but records. The Patwari conducts a special girdawari, noting khasra-wise which plots are lost to water and which are gained from it. The Tehsildar and Collector supervise; mutations follow; and assessments are suspended or revised.

The Punjab Land Administration Manual (Chapter XII) and the Punjab Land Record Manual require this discipline. Without it, land that has vanished from one estate and appeared in another remains a grey zone—breeding dispute instead of closure.

Another legal lens: the Northern India Canal and Drainage Act

There is also the Northern India Canal and Drainage Act, 1873. This statute gives Government control over the waters of all rivers and natural channels for public purposes and protects drainage works against obstruction.

For farmers, this means that if a flood has carved a new, live creek, authorities may treat it as a free-flowing drain or natural channel under State control. You cannot lawfully reclaim or obstruct it without sanction. The ownership of the soil beneath may be disputed, but the control of the channel is the Government’s—reinforcing why encroaching into the fresh channel is both risky and unlawful.

The border reality meets the cadastral reality

Combine these rules with the Ravi’s geography, and the situation is sobering. Unlike other Punjab rivers, where lost land can sometimes be regained when the river shifts again, land lost to the Ravi often flows toward Pakistan.

That is why cadastral precision on the Indian side—mutations, suspensions, boundary fixation—is not just clerical work. It is the only way to secure what can still be secured, before the river nibbles again.

So what should be done now?

Record quickly. Special girdawaris and mutations should be done within weeks, not months. Assessments must reflect diluvion and alluvion fairly.

Fix boundaries where meanders recur. The Collector should invoke s.101-A to stop the annual yo-yo of ownership.

Apply fairness. Use the s.101-B suspension where land is cultivated or valuable.

Enable compensation. Offer s.101-C proceedings where estates want finality and can pay compensation.

Respect drainage law. Treat new creeks as channels under State control; coordinate with irrigation authorities before building embankments or reoccupying soil.

Where “compensation” fits—and where it doesn’t

Two different systems often get confused:

Disaster relief: Payments for crop loss, silt removal, or even land washed away under the State Disaster Response Fund (SDRF). These are essential, but they do not change ownership.

PLRA compensation: A property-law device that transfers suspended land rights upon payment of compensation. This is not relief money—it is a legal settlement of title.

For Ravi-side farmers, only the second can give permanence. The first merely helps tide over the year.

A mindset shift: treat floods as cadastral events

We cannot prevent Himalayan rain. We cannot redraw borders. But we can change how we respond. Floods must be treated as cadastral events. That means:

Surveying and mutating fast,

Fixing permanent boundaries in chronic meander zones,

Using fairness suspensions to prevent injustice,

Applying compensation mechanisms where needed, and

Coordinating with drainage authorities to make protections lawful and lasting.

The British ICS officers—hard-nosed men like Douie and his successors—didn’t write “riverain law” chapters for ornament. They knew that in Punjab, justice begins with a good map. After the Ravi’s fury this year, it must also end with one—drawn in time, signed by the Collector, and strong enough to outlast the next flood.