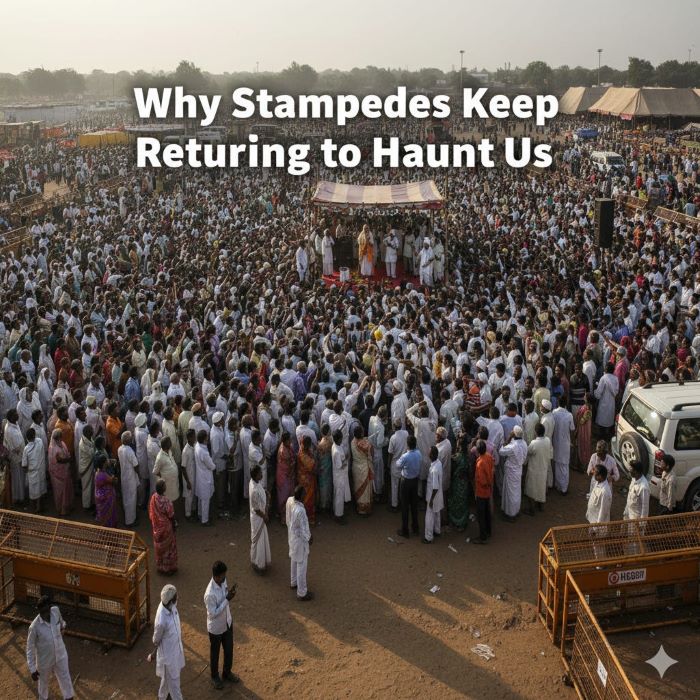

The September 2025 stampede in Karur, Tamil Nadu—where 40 people, including nine children, lost their lives at a rally for actor-turned-politician Vijay—has once again jolted the nation into grief and reflection. The tragedy unfolded in broad daylight, when thousands surged toward the leader’s convoy in sweltering heat, overwhelming every layer of crowd control. What was meant to be a moment of celebration turned in minutes into a mass casualty event. Karur is not an exception but part of a grim continuum. From railway stations to religious gatherings, from sports stadiums to temple queues, India has lived through one such calamity after another. Each disaster is followed by inquiries, reports, and promises of reform, but in practice little changes. Until we design for prevention rather than merely responding after the fact, the cycle is destined to repeat.

The September 2025 stampede in Karur, Tamil Nadu—where 40 people, including nine children, lost their lives at a rally for actor-turned-politician Vijay—has once again jolted the nation into grief and reflection. The tragedy unfolded in broad daylight, when thousands surged toward the leader’s convoy in sweltering heat, overwhelming every layer of crowd control. What was meant to be a moment of celebration turned in minutes into a mass casualty event. Karur is not an exception but part of a grim continuum. From railway stations to religious gatherings, from sports stadiums to temple queues, India has lived through one such calamity after another. Each disaster is followed by inquiries, reports, and promises of reform, but in practice little changes. Until we design for prevention rather than merely responding after the fact, the cycle is destined to repeat.

A Catalogue of Recent Disasters

Tamil Nadu, September 2025

Karur’s tragedy is still raw. The Vijay rally saw massive crowds pour in, far beyond manageable limits. As his bus appeared, the crowd surged forward in the heat, leaving 40 dead and many more injured. Within hours, compensation was announced and a judicial inquiry ordered, but the familiar script offered scant reassurance to the grieving families.

Haridwar, July 2025

Only weeks earlier, Haridwar had witnessed its own fatal crush. The Mansa Devi Temple drew thousands during the Kanwar Yatra, and a narrow path became dangerously clogged. A rumour of electrocution sparked panic, and six people were killed. Despite being a city long used to hosting large gatherings, authorities were caught unprepared.

Bengaluru, June 2025

In Bengaluru, celebration turned to horror when Royal Challengers Bengaluru finally lifted the IPL trophy. A victory parade outside M. Chinnaswamy Stadium, advertised as free-entry, drew far beyond capacity. Eleven fans died as gates buckled under pressure. The lack of controlled entry and poor route design turned a joyous occasion into a tragedy.

Goa, May 2025

At the Sree Lairai Devi Temple in Shirgao, Goa, devotees had gathered for the annual fire-walking ritual. As the crowd pressed forward on a sloping approach, a fall triggered a cascading crush. Six to seven people died, dozens were injured, and once again, a magisterial probe followed.

Delhi, February 2025

The New Delhi Railway Station disaster highlighted how modern infrastructure can become a death trap under unmanaged pressure. On 15 February, pilgrims bound for the Maha Kumbh crowded onto a narrow bridge between platforms. Train delays and sudden platform changes caused panic, and 18 people, including five children, suffocated in the crush.

Prayagraj, January 2025

Barely weeks earlier, the Maha Kumbh itself had seen its worst tragedy. On Mauni Amavasya, millions pressed toward the Sangam for the pre-dawn holy bath. Barricades collapsed under the weight of numbers. Official figures recorded 30 deaths and 60 injuries, but independent estimates suggested the toll was closer to 80. Survivors recounted how cries for help were drowned out by the relentless push of the crowd.

Tirupati, January 2025

At Tirumala’s Venkateswara Temple, a gate opened unexpectedly during the rush for Vaikuntha Ekadashi tokens. Six devotees died and dozens were injured as the queue turned into a surge. An inquiry later identified mismanagement of gates and communication failures, familiar themes in India’s long history of crowd disasters.

Hathras, July 2024

The most haunting of all recent tragedies remains the Hathras disaster. A satsang by a self-styled godman had official permission for 80,000 attendees. Nearly a quarter of a million turned up. When the preacher’s convoy began to leave, thousands surged forward to touch his feet. The crush killed 121 people, mostly women and children. The scale of negligence—both by organisers and officials—was staggering, yet the lessons learned remain unclear.

Why “Stampede” Is the Wrong Word

The very word we use—“stampede”—masks the reality. It suggests panic and irrational behaviour. In truth, these deaths are caused not by hysteria but by physics. Once crowd density crosses about five to six people per square metre, individuals lose the ability to move freely. Breathing becomes difficult, pressure mounts, and small triggers—a fall, a gate opening, a vehicle moving—cascade into catastrophe. People die standing, unable to draw breath, not because they ran but because they could not move at all.

The Hajj Parallel

For those tempted to believe that such disasters are uniquely Indian, the Hajj offers sobering perspective. In June 2024, more than 1,300 pilgrims died in Mecca, most from heatstroke. Temperatures exceeded 51°C, and many unregistered pilgrims lacked access to air-conditioned tents or water facilities. A decade earlier, in 2015, over 2,000 died in a crowd crush during the stoning ritual at Mina. Saudi Arabia had invested billions in infrastructure, but the physics of human density overpowered even the most elaborate planning.

The point is not that prevention is futile, but that prevention must be relentless. If such tragedies can strike the most meticulously planned pilgrimage in the world, how much more urgent is reform in India, where planning is often perfunctory and oversight lax?

The Recurring Ingredients

Every one of these tragedies shares familiar ingredients:

Bottlenecks: narrow bridges, staircases, and temple paths where pressure builds.

Unpredictable triggers: rumours, sudden gate openings, VIP convoys.

Heat and dehydration, which weaken people in high-density conditions.

Permits vs. reality: permissions issued for tens of thousands, but actual turnout in lakhs.

Reactive governance, where inquiries follow but preventive structures rarely endure.

What Would Actually Prevent the Next Disaster

The science is clear; the failures are political and administrative. Preventive bias must replace the culture of inquiry and compensation. What would that look like?

Enforceable Safety Standards

No gathering should proceed without an independently certified crowd-safety plan—defining maximum density, entry and exit routes, and emergency protocols. Just as fire codes are mandatory for buildings, crowd codes must be non-negotiable for public gatherings.

Real-Time Monitoring

Modern tools exist to track crowd density in real time—drones, CCTV, overhead sensors. They must be deployed not as experiments but as essentials. Authorities need the power to halt or redirect flows the moment danger levels are reached.

Smarter Queue and Gate Design

Serpentine queues, one-way routes, and crush-resistant barriers can drastically reduce risk. Most importantly, gates must never open into pressure. This basic rule is broken time and again, with fatal consequences.

Heat and Health Protocols

In a tropical country, heat is not incidental—it is central. Mandatory shaded rest areas, water stations, misting facilities, and medical posts should be standard, particularly for summer events.

Real Accountability

Compensation is not accountability. Organisers and officials who ignore safety norms must face real consequences—fines, licence cancellations, even criminal liability. Without personal stakes, negligence will persist.

The Bias We Need

India excels at reactive governance. Within hours of a tragedy, we see compensation announcements, task forces, and commissions of inquiry. But the true test is not how we respond after lives are lost, but how we prevent such losses in the first place. Preventive measures rarely attract headlines precisely because they succeed silently. Yet, invisible success is the goal.

Shifting to a preventive bias requires more than reports; it requires a cultural shift. We must accept that mass gatherings are part of Indian life—religious, political, social—and treat them with the same seriousness we accord to aviation safety or fire prevention. Only then can we end the grim cycle of mourning, inquiry, and repetition.

Conclusion

The Karur tragedy is not an aberration but the latest entry in a long and shameful record. From Hathras to Haridwar, from Tirupati to Prayagraj, from Delhi to Goa, every incident has told us the same story: crowd crushes are predictable, preventable, and yet neglected. Even the Hajj, with its vast resources, proves that the challenge is formidable. But India’s problem is not inevitability—it is indifference.

Until we choose prevention over reaction, we will continue to live through these cycles of grief, inquiry, and silence, waiting helplessly for the next disaster. The dead deserve better. The living deserve safety not as charity, but as guarantee.