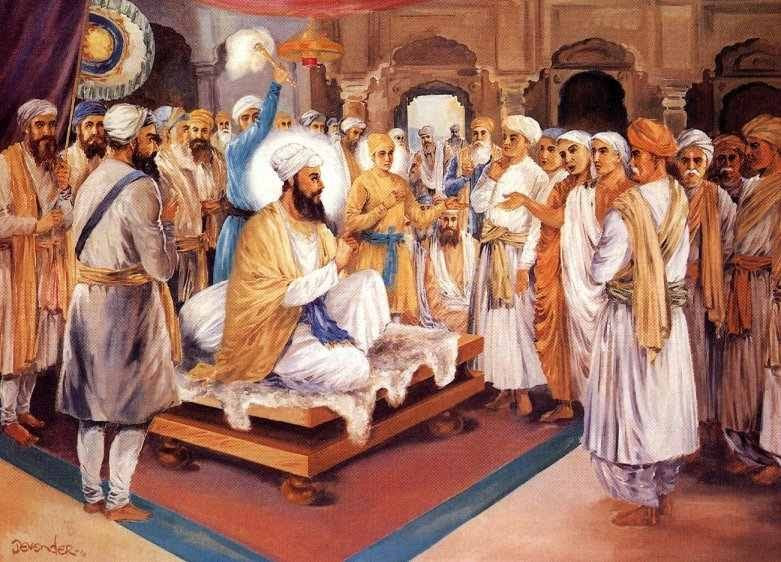

In 1675, India witnessed one of the most extraordinary acts of courage in human history. Shri Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji, the ninth Guru of the Sikhs, stood against the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s campaign of forced conversions. When Kashmiri Pandits sought his help, he rose above religious boundaries to defend the universal right of every human being to follow their own faith. Arrested and executed in Delhi, Guru Tegh Bahadur chose martyrdom over submission. His sacrifice was not for territory or throne, but for humanity’s freedom of conscience.

In 1675, India witnessed one of the most extraordinary acts of courage in human history. Shri Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji, the ninth Guru of the Sikhs, stood against the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s campaign of forced conversions. When Kashmiri Pandits sought his help, he rose above religious boundaries to defend the universal right of every human being to follow their own faith. Arrested and executed in Delhi, Guru Tegh Bahadur chose martyrdom over submission. His sacrifice was not for territory or throne, but for humanity’s freedom of conscience.

Had it not been for his sacrifice — the shield of Hind Di Chadar — Aurangzeb’s intolerant zeal might have forced the conversion of almost the entire Indian subcontinent to Islam. Guru Tegh Bahadur saved India’s spiritual diversity and its right to belief itself. Courtesy Sikhiwiki

This year marks the 350th anniversary of that supreme sacrifice. In November, the Punjab Government will commemorate this milestone in a grand way at Anandpur Sahib — the sacred city founded by the Guru himself. A special session of the Vidhan Sabha is also planned there, with several dignitaries invited to participate in this historic event.

On October 25, 2025, Maharashtra Deputy Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis spoke at a commemorative event in Mumbai honouring Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji’s 350th martyrdom anniversary (link). The program featured the acclaimed Punjabi singer Satinder Sartaj, who performed his moving tribute song to the Guru (watch here).

A Forgotten National Memory

This act of resistance — against tyranny and for religious freedom — lives vividly in Punjab’s collective memory but has rarely found a place in India’s broader national consciousness. Every Punjabi child grows up with the story of Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji. Yet beyond Punjab, his martyrdom remained confined to Sikh remembrance, seldom acknowledged in India’s larger historical narrative. Successive governments failed to give it the honour it deserved.

That changed under Prime Minister Narendra Modi. He brought Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji’s message of courage, sacrifice, and compassion to the national and global stage. When the 400th Parkash Purab was celebrated at Delhi’s Red Fort — the very site of the Guru’s execution — it was unprecedented. The Mughal seat of oppression became the venue for India’s gratitude. Modi’s and the BJP’s tribute was both symbolic and corrective — an acknowledgment of a civilisational debt long overdue (watch here).

Yet despite such sincere efforts, skepticism persists. Many Sikhs — especially in Punjab — remain unconvinced. Each time the BJP or RSS speaks about the Gurus or Sikh legacy, the response is respectful yet hesitant. Why does the government’s shukrana (gratitude) fail to touch Sikh hearts? Why this trust deficit, this instinctive suspicion? Why the disconnect — even hostility — despite genuine gestures?

Is it the result of decades of political conditioning — the continuous psychological hammering of “Panth khatre vich hai” (the faith is in danger) for narrow political gain? Have such manipulative narratives hardened into a collective fear? These are questions that must be answered — but not by those responsible for planting that fear in the first place.

Is former Member of Punjab Public Service Commission

A farmer and keen observer of current affairs

Recognition and the Risk of Regression

The long-standing demand for a separate Anand Karaj Marriage Act was finally fulfilled, giving Sikhs a distinct legal identity in marriage law for the first time. The Centre has now directed states to frame rules for its implementation, following a Supreme Court order in September 2025.

However, a troubling debate is emerging. Some voices within the DSGMC reportedly propose denying the Anand Karaj ceremony to Sikhs who cut their hair — labelled patits by orthodox authorities. Such exclusionary thinking could push Sikhs like me back under the Hindu Marriage Act, undoing the very inclusivity the Anand Marriage Act was meant to guarantee.

If this happens, the government’s effort to recognise Sikh identity could be undermined by those controlling Sikh religious institutions. Unfortunately, these bodies — SGPC, DSGMC, and others — have too often steered Sikh traditions to serve political or financial interests. This drift began soon after the passing of Guru Gobind Singh Ji and sadly continues even today.

A question for later: who and what defines a ‘patit’?

The Meaning of Shukrana

In Sikh philosophy, shukrana is not mere gratitude — it is humility expressed through fairness, sincerity, and service. It demands deeds, not declarations. When leaders praise Sikh Gurus yet fail to honour Punjab’s rights or address its core issues, their shukrana sounds hollow. Guru Tegh Bahadur stood for truth translated into action. Those who invoke his name must live by that principle.

Beyond Symbolism: The Need for Substance

The Modi government has done more than any before it to bring Sikh history into the national spotlight — opening the Kartarpur Corridor, commemorating the Sahibzadas as Veer Bal Diwas, and celebrating Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji at the Red Fort. These gestures are commendable. But Punjab’s measure for sincerity is different.

The Sikh masses whom Modi seeks to connect with live in rural Punjab — among farmers, traders, and labourers. Their discontent is both sentimental and material: the pressure of unsustainable agriculture, unpaid crop dues, falling groundwater, uncertain MSP, broken promises over Chandigarh, and unresolved river-water disputes. When these remain unaddressed, even the grandest gestures appear theatrical.

Symbolism without substance breeds cynicism.

The Weight of History and Identity

Punjab’s mistrust is rooted in experience. The wounds of 1984 — the assault on the Golden Temple, the killings, and the delayed justice — still ache. Social media keeps them alive. A moderate political Sikh leader who ruled Punjab for decades built their politics around the slogan “Panth khatre vich hai”, turning it from an idea into a genetic instinct.

Sikh society itself is not uniform. Nihangs, Namdharis, Nanakpanthis, urban professionals, and rural farmers all think differently. A Sikh in Delhi may feel secure within a cosmopolitan identity, while one in Tarn Taran may see the denial of Chandigarh as Punjab’s capital as a continuing betrayal. Meanwhile, moderate voices have weakened, and hardliners dominate the discourse — amplifying hostility toward Delhi and erasing genuine goodwill.

Bridging the Trust Deficit

If the BJP and RSS want their shukrana to be accepted as genuine, they must move from shukrana to seva — from words to work. They must:

• Resolve the Chandigarh capital issue and river-water disputes with fairness and finality. The proposed canal bringing surplus Indus water to Punjab and Haryana is a step in the right direction.

• Clarify constitutional ambiguities — especially the reference to Sikhs under Hindu law in Article 25 of the Constitution.

• Deliver justice in 1984 cases through transparent, time-bound processes.

• Let credible Sikh voices from Punjab lead engagement and feedback. Those with vested interests or sectarian loyalties cannot represent the community’s conscience. Trust grows from within, not from above.

• And above all, ensure the immediate release of Sikh prisoners who have completed their sentences. Their continued incarceration offends justice and faith alike, and no gesture of gratitude will resonate until their freedom is restored.

A Final Word

Guru Tegh Bahadur’s martyrdom was not for one community; it was for humanity’s right to freedom of religion and belief. Modi deserves credit for restoring that legacy to national consciousness. But remembrance without reform will not heal the divide.

Punjab needs justice with sincerity. The time has come to replace performative gratitude with participative governance — and shukrana with seva. Only then will Delhi’s gratitude truly find its way into Punjab’s heart.