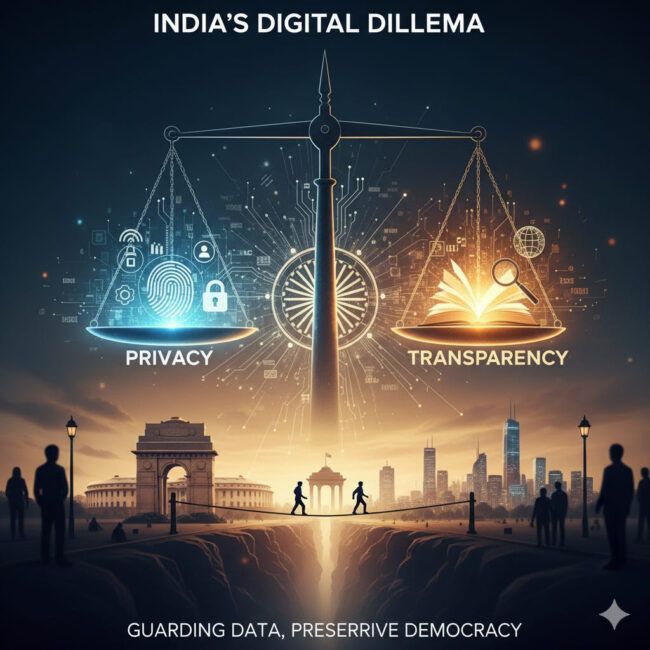

On 13 November 2025, India brought into force its first comprehensive data protection regime by notifying the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Rules, 2025. This move operationalised the DPDP Act, 2023—legislation passed in August 2023 after two decades of committee reports, public debate, and policy drafts. For the first time, India has a unified legal framework that defines citizens’ digital privacy rights, establishes compliance obligations for data handlers, and creates enforcement mechanisms.

On 13 November 2025, India brought into force its first comprehensive data protection regime by notifying the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Rules, 2025. This move operationalised the DPDP Act, 2023—legislation passed in August 2023 after two decades of committee reports, public debate, and policy drafts. For the first time, India has a unified legal framework that defines citizens’ digital privacy rights, establishes compliance obligations for data handlers, and creates enforcement mechanisms.

The journey to this point reflects India’s struggle to reconcile rapid digitalisation with the constitutional promise of privacy as a fundamental right. The operational challenge now is to ensure that this framework safeguards individual autonomy without stifling transparency or technological innovation.

Centralised Rule-Making, Consultative Drafting

Under Section 40 of the DPDP Act, the power to frame rules rests solely with the Union Government across more than two dozen operational domains—from consent formats and breach notifications to the functioning of the Data Protection Board. Unlike Europe’s distributed model, where independent regulators enjoy parallel rule-making powers, India’s framework remains centralised.

Yet, this top-down structure was tempered by a wide-ranging consultation process. The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) opened the draft rules for public comment in early 2025, extending deadlines and holding in-person consultations in seven major cities. Start-ups, industry bodies, civil society groups, and government departments all participated. The process marked an important acknowledgment that privacy cannot be protected without public participation.

Consent at the Core: Empowering Digital Citizens

At its heart, the DPDP Act builds a consent-based system. Data Fiduciaries must obtain “free, specific, informed, unconditional, and unambiguous” consent through clear standalone notices in plain language. This emphasis on simplicity is crucial in a country where millions are first-generation digital users.

A uniquely Indian innovation is the creation of Consent Managers—licensed intermediaries who help citizens view, grant, or withdraw data permissions across multiple platforms. If implemented well, this could democratise data governance and reduce the asymmetry between individuals and tech giants.

Special protection for children’s data adds another layer of rigour. No processing of minors’ data can occur without verifiable parental consent, and profiling or targeted advertising directed at children is prohibited. Verification options range from DigiLocker tokens to voluntary document submissions—offering flexibility without mandating a single identity system.

Breach Reporting and Retention Discipline

Security and accountability run through the Rules. Once a data breach occurs, fiduciaries must inform both the affected individuals and the Data Protection Board within 72 hours—detailing the nature, consequences, and remedial measures. Logs and relevant data must be retained for at least a year for breach detection and investigation.

The regime also enforces purpose limitation: personal data must be erased once the purpose of processing is fulfilled unless required for legal retention. Sector-specific norms—especially for e-commerce, gaming, and social media—add precision. This transition from limitless storage to disciplined retention could fundamentally reshape India’s data culture.

The Constitutional Lodestar

In K.S. Puttaswamy (2017), Justice R. F. Nariman affirmed that the right to privacy is a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution. Any intrusion into personal data must therefore satisfy the constitutional test of being fair, just, and reasonable—both in substance and in procedure. This requires clear legality, demonstrable necessity, strict proportionality, and robust safeguards against abuse. India’s data protection framework is not merely a compliance checklist; it must withstand constitutional scrutiny whenever the State or a powerful intermediary handles personal data, whether through statutory rules or executive action taken thereunder.

The RTI Conundrum: Privacy at the Cost of Accountability?

The most controversial fallout of the DPDP Act lies beyond data servers—it strikes at the heart of transparency. Section 44(3) amends the Right to Information (RTI) Act by deleting the “larger public interest” test that once allowed disclosure of personal information when transparency outweighed privacy concerns.

Activists and journalists warn this amendment could muzzle accountability. Asset declarations, service records, or disciplinary findings of public officials—previously accessible through RTI—might now be shielded under the guise of privacy. The government maintains that Section 8(2) of the RTI Act still permits disclosure in the public interest, but that clause is discretionary, not mandatory.

In essence, what was once an obligation to balance privacy with public interest now becomes an option. Without a judicially evolved balancing test, bureaucratic discretion may tilt towards secrecy, weakening one of India’s most vital democratic tools.

Global Benchmarks: GDPR, CCPA, and the Indian Middle Path

India’s law inevitably invites comparison with global privacy regimes. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) remains the gold standard—broad in scope, principles-driven, and anchored in independent regulators. The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) emphasises consumer control and introduces a private right of action for breaches.

The DPDP Act borrows selectively from both. It applies extraterritorially to entities offering goods or services in India, similar to the GDPR. But unlike California, its obligations apply to businesses of all sizes, not only large ones. Its reliance on consent as the main legal basis for processing is narrower than Europe’s six legal bases, yet broader than earlier Indian drafts.

Where the DPDP Act stands apart is in imposing duties on citizens—including penalties for frivolous complaints. No other major regime penalises individuals for asserting their data rights. The intent may be to deter misuse, but it risks discouraging legitimate grievances.

Cross-border data transfer rules reveal a similar tension between openness and control. The government may restrict transfers to specified countries or mandate data localisation for undefined “classes of data.” Such flexibility may appeal to policymakers but could unsettle global investors seeking predictability.

Enforcement Muscle and Missing Teeth

The penalty framework is muscular: fines up to ₹250 crore for security failures and ₹200 crore for violations relating to children’s data. However, unlike the GDPR, penalties are capped rather than pegged to global turnover. Nor does the Indian law allow individuals to sue for damages; enforcement rests entirely with the Data Protection Board.

That places extraordinary responsibility on a new institution whose credibility will hinge on independence, transparency, and technical competence. Without an impartial and proactive Board, enforcement risks becoming selective or perfunctory.

Finding the Balance: Privacy, Transparency, and Innovation

India’s DPDP regime is, in many ways, a pragmatic middle path—modern yet cautious. It acknowledges implementation realities with a phased 18-month rollout. It introduces innovative consent architecture and aligns security obligations with global norms. But it also reveals the anxieties of a state balancing control and freedom in the digital age.

Going forward, three imperatives stand out. First, courts and information commissions must evolve jurisprudence that harmonises privacy and transparency rather than allowing one to eclipse the other. Second, the Data Protection Board must demonstrate institutional independence and set precedent through reasoned, published decisions. Third, India should clarify cross-border transfer criteria to build investor confidence and facilitate global data flows essential for innovation.

In summary: The Promise and the Peril

No doubt, this initiative enjoyed strong political backing from the Prime Minister, but it equally deserves acknowledgment for the Minister of Electronics and Information Technology, Ashwini Vaishnaw, who personally vetted the rules and steered an expansive consultation process with a wide range of stakeholders across the country. His effort lent credibility and inclusiveness to what could otherwise have been a purely bureaucratic exercise.

India’s digital privacy law is neither a perfect clone of the GDPR nor a diluted imitation of American state laws—it is a genuinely home-grown experiment in balancing rights, responsibilities, and realities, informed as much by the uses, as by the abuses, of the Right to Information Act, 2005. If implemented with integrity, it has the potential to empower citizens, strengthen cybersecurity, and position India as a trusted and responsible digital economy.

But if privacy becomes a pretext to weaken transparency—including the key provisions of the RTI Act—or if centralised control stifles accountability, the law could end up protecting power rather than people. The true measure of the DPDP Act’s success will lie not in how it reads on paper, but in how faithfully it upholds two ideals that define a modern democracy—the right to be left alone and the right to know.