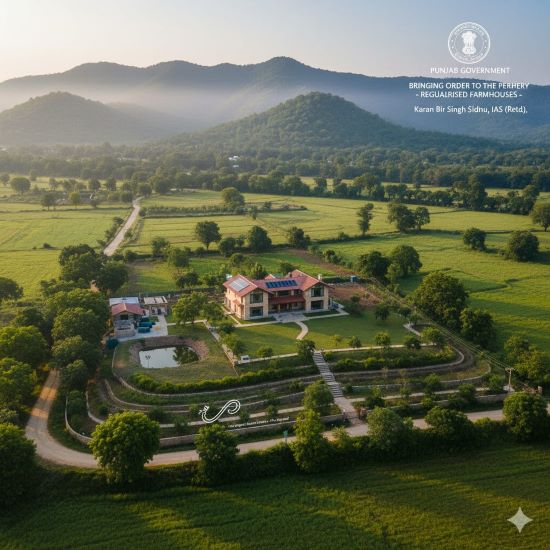

In the meeting of the Punjab Cabinet, held with Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann in the chair on Saturday, 15 November, a number of progressive decisions were taken. What stands out is this policy—a new framework for Low Impact Green Habitats (LIGH) that regularises eligible existing farmhouses on minimum 4,000 sq. yd. plots and also permits fresh approvals. In the periphery of Chandigarh—especially SAS Nagar (Mohali) and Rupnagar (Ropar)—unplanned growth and departmental cross-talk long outpaced policy. The outcome has been a patchwork of ad-hoc decisions, litigation, and avoidable friction. A clear rulebook, applied across the State, was overdue.

In the meeting of the Punjab Cabinet, held with Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann in the chair on Saturday, 15 November, a number of progressive decisions were taken. What stands out is this policy—a new framework for Low Impact Green Habitats (LIGH) that regularises eligible existing farmhouses on minimum 4,000 sq. yd. plots and also permits fresh approvals. In the periphery of Chandigarh—especially SAS Nagar (Mohali) and Rupnagar (Ropar)—unplanned growth and departmental cross-talk long outpaced policy. The outcome has been a patchwork of ad-hoc decisions, litigation, and avoidable friction. A clear rulebook, applied across the State, was overdue.

Ending the PLPA Muddle

Much of the confusion stemmed from “delisted numbers” under the Punjab Land Preservation Act, 1900 (PLPA). Although various parcels stood delisted, conditions prohibiting commercial use remained, and bona fide homesteads or farmhouses never enjoyed a stable, uniform regime. The Housing & Urban Development Department and the Forest Department often read the law at cross-purposes—the latter frequently maintaining that Government of India’s permission was necessary because the land was “deemed forest”. Where municipal jurisdictions overlapped, Local Government bodies added further approvals. The new policy offers a pragmatic consolidation: it clarifies what is permissible, what is proscribed, and who decides—an administrative relief that should reduce contradictory orders and case-by-case improvisation.

Two Tracks, One Objective

The policy rests on two strands. First, regularisation of eligible existing structures—at a premium—acknowledges ground realities while disincentivising illegality. Second, fresh approvals provide a lawful pathway for future development that is orderly and environmentally cautious. This twin approach draws a line under the past and prevents tomorrow’s disputes by offering a clear, prospective route.

Guardrails that Rein in Sprawl

Crucially, the framework is not a free-for-all. It insists on low intensity by limiting ground coverage to 10% and capping height to ground plus one. That ensures no high-rise clutter to block the Shivalik vistas. The 4,000 sq. yd. minimum guards against the kind of haphazard densification that blighted belts like Nayagaon-Kansal-Karoran and parts of Zirakpur, where government had to sprint behind reality with hurried notified areas or upgraded local bodies. In short: fewer, greener, and better-regulated footprints.

Environmental Duties, Not Box-Ticking

Sustainability obligations—rainwater harvesting, solar readiness, wastewater and solid-waste management, and native tree planting—are baked in. The no-commercial-use rule prevents backdoor resorts, short-stay rentals, and office activity. Where land lies near the Sukhna Wildlife Sanctuary, natural drains, or defence installations around Mullanpur, additional No-Objection Certificates and statutory safeguards remain mandatory. These are not ornamental clauses; they are the difference between a landscape that breathes and one that buckles under incremental abuse.

District-Sensitive Pricing, Transparent Logic

Rates recognise district-wise differentials: Mohali attracts the highest rate, Ropar next, and other districts the base rate. That tiering reflects location pressure and ecological sensitivity. The policy’s legitimacy, however, will depend on transparent notification, time-bound processing, and predictable annual escalations—the antidote to corridor whispers and the cynicism they breed.

Basic rates (per sq. yd.):

SAS Nagar (Mohali): ₹1,200 (i.e., 4× the base of ₹300)

Rupnagar (Ropar): ₹600 (i.e., 2× the base)

All other districts: ₹300 (base rate)

Note: Once fixed, the base is valid for one year and rises 10% on 1 April each year.

Pricing Clarity: Fresh vs Regularisation

A fair feature of this policy is that regularisation costs more than a new approval—appropriate, since it prices past non-compliance. Consider a 4,000-sq. yd. plot in Mohali:

Fresh approval: ₹1,200 × 4,000 = ₹48,00,000 (₹48 lakh).

Regularisation (existing structures): twice the rate → ₹96,00,000 (about ₹1 crore) for the same 4,000 sq. yd. farmhouse.

These headline figures sit before adding Change of Land Use (CLU) charges, building-plan sanction fees (based on built-up area; with 10% coverage and G+1, built-up ≈ 7,200 sq. ft.), and any other statutory or environmental clearances where applicable. Even so, the signal is unmistakable: fresh compliance is cheaper; regularisation is a costly correction.

The Critics and the Arithmetic

Some critics warned—while the initiative was still on the anvil—that the policy would reward flouters or coddle a land mafia comprising powerful politicians, bureaucrats, or police. The Mohali arithmetic should temper that claim. ₹48 lakh for a lawful fresh approval and ~₹1 crore for regularisation on a 4,000 sq. yd. unit is not a sop; it is a substantial financial commitment calibrated to district pressure. Add CLU, plan-sanction, and sustainability compliance, and the incentive structure clearly rewards the regular route and penalises past violations. The 10% ground-coverage and G+1 cap further dampen speculative densification and protect sightlines to the Shivaliks.

Implementation: How to Make It Work

Three administrative habits will decide outcomes:

Single-Window Clarity

A unified, online checklist—CLU, building plan, forest/wildlife NOCs, drainage/fire/environment—reduces discretion and delay. Applicants should see real-time status, required documents, and timelines.

Independent Vetting & Post-Approval Audits

Randomised inspections and satellite-based checks can verify hard-surface caps, native plantation, zero-discharge norms, and height/coverage limits. Violations must bring real penalties, including cancellation.

Open Data on Rates, Approvals, and Violations

Publishing district-wise rates, approvals granted, refusals, and enforcement actions dissuades collusion and reassures citizens that the rules are applied fairly.

A Sensible Middle Path

The State had to choose between turning a blind eye to reality and weaponising prohibitions that push activity underground. It has chosen a middle path: permit environmentally tolerable homesteads; regularise with real costs where feasible; and bar commercialisation that would alter the area’s character. In doing so, it advances legal certainty, environmental prudence, and predictable urban form—key ingredients for a liveable periphery along the Shivalik foothills and beyond.

Conclusion: Mild Applause—With Watchful Eyes

This is a progressive, balanced response to a long-festering problem. It should reduce litigation, resolve departmental turf issues, and channel development into compliant, low-impact homesteads—especially around Mohali and Ropar, but ultimately across Punjab. Those criticising the initiative might consider the cost arithmetic: in Mohali, ₹48 lakh for a fresh approval versus ~₹1 crore for regularisation on a 4,000 sq. yd. farmhouse scarcely resembles a free pass. The Housing & Urban Development Department, and its political and bureaucratic leadership, merits appreciation for a fair and workable design. The harder part begins now: transparent rates, strict enforcement, and zero tolerance for commercial misuse. If government matches policy with practice, the periphery can be greener, calmer, and more lawful—by design, not by chance.