The changing immigration environment in the United States has had a deep and disproportionate impact on Punjabi migrants. For decades, Punjab’s social and economic landscape has been closely tied to overseas migration, particularly to North America. The U.S. was seen as a destination of stability and opportunity, but in recent years that dream has come under severe strain. Stricter immigration rules, aggressive enforcement by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and faster deportation processes have turned migration into a high-risk journey for thousands of Punjabi youths and families.

The changing immigration environment in the United States has had a deep and disproportionate impact on Punjabi migrants. For decades, Punjab’s social and economic landscape has been closely tied to overseas migration, particularly to North America. The U.S. was seen as a destination of stability and opportunity, but in recent years that dream has come under severe strain. Stricter immigration rules, aggressive enforcement by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and faster deportation processes have turned migration into a high-risk journey for thousands of Punjabi youths and families.

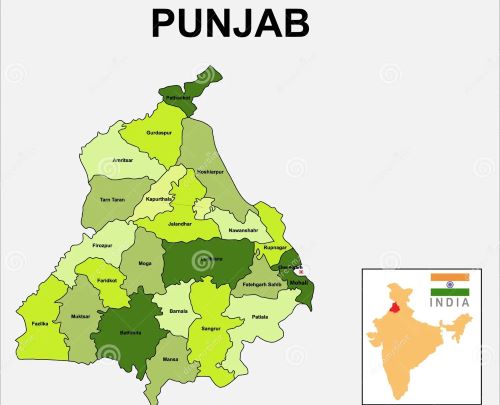

Punjab has emerged as one of the largest source regions among Indians facing arrest and deportation from the United States. A significant share of Indians removed from the U.S. in the last two to three years belong to Punjab, especially young men from Doaba, Majha, and Malwa belts. Many initially entered legally on student or visitor visas but later overstayed due to lack of work opportunities or delays in changing status. Others took irregular routes after being misled by travel agents promising guaranteed entry and settlement.

Arrests of Punjabi nationals by ICE have increased as part of wider “interior enforcement” across U.S. cities. These arrests usually take place at workplaces, residences, traffic stops, or during routine immigration check-ins. Importantly, the majority of arrested Punjabis are not involved in serious criminal activity. Most cases relate to immigration violations such as visa overstays, failure to maintain student status, or missing court hearings. Community groups and legal advocates repeatedly point out that immigration violations are being treated almost like criminal offenses, even when there is no threat to public safety.

Among arrested Punjabi migrants, only a smaller portion have criminal records. Those cases generally involve non-violent offenses such as driving under the influence (DUI), minor drug possession, or past convictions linked to financial or documentation fraud. Serious violent crime among Punjabi migrants remains rare. However, under current U.S. policy, even minor criminal convictions can make a non-citizen a priority for detention and deportation. This has led to situations where Punjabis who lived in the U.S. for many years, worked legally, and raised families are suddenly detained and removed.

Deportations of Punjabi migrants have risen sharply. In recent years, thousands of Indians have been deported annually from the U.S., and Punjabis form a large share of this number. Many deportees had no criminal background and were removed solely due to immigration status issues. Deportation often happens abruptly, with little time for families to prepare. People are sent back to India in handcuffs, sometimes after months in detention centers, leaving behind spouses, children, jobs, and homes in the U.S.

The human cost of deportation in Punjab is devastating. Families that invested lakhs of rupees—often by selling land or taking heavy loans—are pushed into financial ruin. Returned migrants face social stigma, unemployment, and mental health struggles. Villages that once celebrated “foreign returns” now quietly absorb young men coming back with nothing but debt and trauma. Parents who dreamed of stability through migration are left broken, both emotionally and economically.

Punjabi students are another vulnerable group. Thousands study in U.S. colleges hoping to move into legal employment later. With stricter monitoring of attendance, work authorization, and documentation, even small mistakes can lead to visa termination, arrest, or deportation. For families in Punjab, a student’s deportation is not just a personal failure—it becomes a public humiliation and a financial disaster.

Women and children are silent victims of this crisis. Punjabi wives in the U.S. face sudden separation when husbands are detained. Children, many of them U.S. citizens, are left without parents or forced to return to India to an unfamiliar environment. Elderly parents in Punjab wait endlessly for remittances and reunions that may never happen.

In conclusion, the story of Punjabi migration to the United States has entered its most painful chapter. Arrests and deportations are no longer rare exceptions but a growing reality. While a small number of cases involve criminal records, the overwhelming majority of Punjabis caught in enforcement actions are victims of harsh immigration laws, limited legal pathways, and exploitation by agents. This crisis calls for serious introspection in Punjab, stronger legal awareness, strict action against fraudulent migration networks, and greater support for deported individuals. Without such measures, the Punjabi–American migration story will continue to be written in loss, fear, and broken dreams.