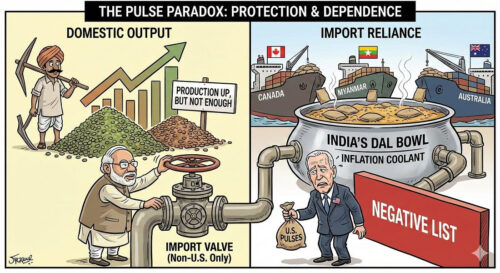

India’s pulses story is a political economy riddle dressed up as a food-security success. On paper, we have done much that is “right”: policy attention has deepened, production has climbed, and the state has repeatedly signalled a national objective of self-sufficiency. And yet, in the market, the dal bowl continues to depend on foreign harvests—often in the very months when domestic prices threaten to flare into headline inflation. The latest twist makes the contradiction sharper still: India has ramped up domestic production and simultaneously kept pulses on a “negative list” in the interim India–U.S. trade framework—no tariff relief, no preferential opening—even while importing heavily from non-U.S. suppliers under the ordinary MFN regime.

India’s pulses story is a political economy riddle dressed up as a food-security success. On paper, we have done much that is “right”: policy attention has deepened, production has climbed, and the state has repeatedly signalled a national objective of self-sufficiency. And yet, in the market, the dal bowl continues to depend on foreign harvests—often in the very months when domestic prices threaten to flare into headline inflation. The latest twist makes the contradiction sharper still: India has ramped up domestic production and simultaneously kept pulses on a “negative list” in the interim India–U.S. trade framework—no tariff relief, no preferential opening—even while importing heavily from non-U.S. suppliers under the ordinary MFN regime.

That combination—rising domestic output, high reliance on imports, and deliberate exclusion of U.S. pulses from negotiated tariff concessions—is precisely what produces the paradox. It is not that India does not need imported pulses. It plainly does. It is that India wants imports without surrendering the ability to switch policy on and off at short notice.

A decade of gains, but not enough dal

Let us begin with the part of the story Delhi is entitled to claim. Over the last decade, pulses output has risen materially, helped by targeted programmes, MSP signalling, seed initiatives and an expanded policy focus on protein security. The numbers tell a real story of progress.

But dal is the sort of commodity where “improvement” does not equal “adequacy”. Consumption grows with population, incomes and nutrition awareness, while production remains exposed to monsoon variability and dryland constraints. Crucially, the shortfalls are recurrent in the very varieties that shape kitchen budgets and inflation headlines—tur, urad and masur. When these tighten, governments do not have the luxury of ideological purity. They reach for imports.

This is what makes pulses different from many other farm commodities. The politics is always on a hair-trigger. A shortage becomes an inflation issue fast; an import surge becomes a farmer distress issue just as quickly. Pulses sit at the intersection of consumer anger and farm lobbying, and policy is forced into constant balancing acts.

Imports as an anti-inflation valve

That balancing act has increasingly taken the form of using imports as a pressure-release valve. In recent years, and especially after weaker domestic output in certain seasons, India has opened the import window aggressively to contain retail prices. Duties are waived or cut on select items; quantitative restraints are relaxed; traders are encouraged—quietly or explicitly—to bring in supplies.

Then, once prices soften and the political complaint shifts from “dal is too expensive” to “imports are crushing farmgate rates”, the approach flips. Duties are reinstated—often in the 10–30 per cent range—and the government presents the move as “relief” for Indian farmers. We have seen this thermostat-style governance repeatedly: duty-free or low-duty windows for tur, urad, masur and yellow peas to tame prices, followed by fresh tariffs once imports begin to depress domestic prices, with lentils and yellow peas being particularly visible examples.

This is not incoherence. It is a governing technique: protect consumers in a tight year; protect farmers when import flows begin to undercut domestic prices. It allows a government to claim it has served both constituencies—often within the same financial year.

Why imports are diversified, not U.S.-centric

A second pillar of the paradox is geographical. India’s pulse imports are diversified, not U.S.-centric. The bulk typically arrives from Canada, Myanmar, Australia, Russia and parts of Africa. India has also tested and expanded lines with Latin American producers, signalling a deliberate strategy of widening the supplier base.

The United States, by contrast, is a marginal supplier in India’s pulse import basket. That fact is important, because it punctures a simplistic narrative that India is “blocking the U.S.” in order to reduce imports altogether. India is not reducing imports; it is importing broadly. What it is doing is managing the import regime on its own terms—through MFN rules and time-bound notifications that can be reversed quickly.

Which brings us to the real question: if India is importing anyway, and if diversification is already in play, why keep pulses “sensitive” in the India–U.S. trade framework?

The negative list logic: protection, flexibility, leverage

The decision to keep pulses on a negative list—and to group them with other politically sensitive farm sectors—tells you what Delhi values most: control. A trade agreement is not a casual customs notification. It is a reciprocal instrument that locks in expectations, narrows discretion, and carries reputational and legal consequences if reversed.

From Delhi’s side, three logics converge.

First, staple politics. Pulses are treated, politically, in the same mental category as wheat and rice: daily essentials, grown largely by small and medium farmers in rain-fed and dryland regions. Any perception of “opening the gates” to foreign competition—especially from a farm economy like the U.S., which is viewed as heavily supported and highly mechanised—is toxic. Even when imports are unavoidable, governments prefer the optics of temporary necessity, not permanent liberalisation.

Secondly, unilateral manoeuvring room. India wants the ability to drop duties to zero for all origins in a tight year, and then rapidly re-impose duties when domestic prices soften and farmgate pressure mounts. That swing—between 0 and 30 per cent, sometimes within short intervals—is central to India’s price-management approach. Binding tariff concessions to a specific partner would constrain that ability. Once you have promised one country a lower tariff, every subsequent “switch back” becomes diplomatically costly and legally contentious.

Thirdly, bargaining leverage. In trade negotiations, concessions are traded for concessions. Pulses may look humble, but in a negotiation they are a chip—especially when U.S. farm lobbies are vocal about market access. Delhi’s instinct is to avoid giving away politically sensitive access unless it receives gains elsewhere that are strategically worthwhile. If pulses are conceded early, the negotiating space narrows; if pulses are held back, Delhi retains leverage for issues it values more.

Put bluntly: India is not refusing U.S. pulses because it does not need pulses. India is refusing because it wants to keep the import tap available without giving up the right to shut it whenever domestic politics demands.

Why import from others, then?

This is where the paradox becomes most visible. India imports heavily from Canada, Myanmar, Russia, Australia and Africa; it can also diversify to Latin America. So why offer nothing to the U.S.?

Because imports from existing suppliers operate under India’s MFN regime and under short, renewable, time-bound policy notifications. Delhi can “discipline” those inflows by reinstating duties—exactly as it has done with lentils and yellow peas—without reopening a high-profile bilateral pact. The act is domestically framed as ordinary price-management. It does not become a diplomatic confrontation.

A bilateral concession to the U.S., however, would sit inside a politically charged narrative of an “India–U.S. deal”, and any later reversal would invite pressure, retaliation threats, and headlines about India “backtracking”. It would harden a flexible, domestic instrument into a treaty-like commitment. Delhi’s instinct is to avoid turning kitchen economics into foreign policy drama.

The deal can still entrench import dependence—indirectly

Even with pulses excluded, the broader architecture of a trade framework can make it easier for the state to live with the import-dependent equilibrium. If India wins improved access for its exports in other categories—processed foods, textiles, selected agricultural products, or other tradable lines—it creates political room. The government can point to overall gains, while keeping the core staples protected. That macro comfort can reduce the urgency to confront the toughest structural task: making pulses cultivation reliably profitable and productivity-led at scale.

Meanwhile, the global surplus pulses market remains available. India’s willingness to keep toggling duties for non-U.S. origins ensures that global supplies continue to flow in whenever domestic prices spike. The U.S. may remain outside the preferential window, but the import valve stays very much open for everyone else.

Protection plus dependence: the uneasy equilibrium

So we arrive at the configuration that sustains the paradox:

At the farm gate, governments promise higher MSPs, procurement support and a narrative of imminent self-sufficiency. Farmers are told they are being shielded from cheap imports, with the negative list showcased as evidence of firmness.

In the market, whenever output falters or prices threaten to spike, the state opens the import tap: duties fall, restrictions loosen, and a few million tonnes are drawn from diversified origins. Once domestic prices soften and farmer lobbies complain, duties return, framed as protection.

This allows the state to claim it is both protecting farmers and protecting consumers. The cost is the uneasy equilibrium that has now become familiar: persistent import dependence despite real production gains and a decade of programmes.

A more honest bargain

If India wishes to keep pulses off negotiated tariff concessions—a defensible stance—it owes the country two forms of honesty.

First, predictable domestic rules. If we are serious about pulses self-sufficiency, farmers must see stable, credible price signals and procurement mechanisms that do not vanish precisely when global imports surge. Pulses cannot be treated as a moral cause in speeches and an administrative nuisance in markets.

Secondly, transparent import doctrine. Rather than ad-hoc duty toggles that surprise farmers and traders alike, India should publish clear triggers linked to buffer stocks, retail price bands, and crop estimates. If we must import in bad years, the framework should be rule-bound, not improvised.

Until then, the paradox will persist. India will produce more pulses—and still import millions of tonnes. It will keep pulses out of the India–U.S. deal to preserve political control—and still rely on non-U.S. suppliers to cool the dal pot whenever prices rise. And it will continue to claim the mantle of protection on both sides—while quietly admitting, through the import window, that self-sufficiency remains a promise still in progress.