On 13 February 2026, a Bench of the Supreme Court comprising Justice Vikram Nath and Justice Sandeep Mehta delivered a reportable, 63-page judgment in Harbinder Singh Sekhon & Ors. v. State of Punjab & Ors.

On 13 February 2026, a Bench of the Supreme Court comprising Justice Vikram Nath and Justice Sandeep Mehta delivered a reportable, 63-page judgment in Harbinder Singh Sekhon & Ors. v. State of Punjab & Ors.

At one level, the case concerned a proposed cement grinding unit of the Shree Cement group on land that was, in planning terms, essentially agricultural in Sangrur district, Punjab. At another, it became a reaffirmation of two constitutional fundamentals: that statutory planning frameworks are binding, and that preventive environmental safeguards cannot be diluted by administrative convenience—particularly when the consequences fall on communities, habitations, and schools.

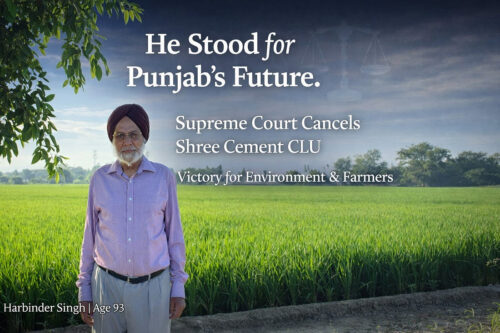

But there is a third, quieter story that gives this litigation its moral force. One of the petitioners was 93 years old. His civil writ petition had been dismissed by the Punjab and Haryana High Court, yet he did not retreat into resignation. Led in the Supreme Court by Senior Advocate Mukul Rohatgi, he persisted, travelled the long constitutional road, and succeeded. In an age of cynicism about access to justice, that fact alone deserves reflection—because it reminds us that constitutional remedies can still be real for ordinary citizens, even when the first courtroom door has closed.

The Context: A CLU in an Agricultural Zone

The dispute arose from a Change of Land Use (CLU) dated 13 December 2021, granted in favour of a cement-related industrial unit. The land fell within a rural agricultural zone under the notified Master Plan for Sangrur. Local agriculturists and a nearby school challenged the permission.

The Punjab and Haryana High Court dismissed their civil writ petitions, holding that a subsequent “approval” by the statutory Punjab Regional and Town Planning and Development Board in January 2022 effectively cured the defect in the CLU. The 93-year-old petitioner and others approached the Supreme Court thereafter, impugning this judgment.

The central legal question was deceptively simple:

Can an executive permission override an operative statutory Master Plan?

The Master Plan Is Law, Not Advice

The Supreme Court’s answer was unequivocal. Under the Punjab Regional and Town Planning and Development Act, 1995 (commonly known as the PUDA law), a Master Plan is not a policy guideline but a statutory instrument. It comes into legal force only after a defined public process—publication, an opportunity for citizens to file suggestions, claims and objections, and a final notification in the Official Gazette. Once it comes into operation, it binds both the State and the citizen.

Section 79 of the Act contains a prohibition: land use must conform to the Master Plan.

A Change of Land Use (CLU), the Supreme Court held, is not a device to sidestep zoning or the Master Plan’s land-use framework. It is merely a regulatory permission, and it presupposes conformity with what the Plan allows. If the land lies in a rural agricultural zone where a red-category industry is impermissible, no administrative order—even if styled as a “resolution” or “approval” of a statutory Board—can lawfully convert that site into an industrial enclave.

This part of the judgment restores discipline to planning law. Across India, Master Plans are too often treated as flexible guidelines, adjusted informally in the name of facilitation or investment. The Apex Court has reminded us that planning certainty is not a bureaucratic inconvenience—it is a legal safeguard.

Ex-Post Facto Approval Cannot Cure Illegality

The Punjab and Haryana High Court had reasoned that a Planning Board “approval” recorded on 5 January 2022 validated the CLU retrospectively.

The Supreme Court rejected this reasoning.

Minutes of a meeting are not the same as a statutory amendment. If land use is to be altered, it must be done in the manner prescribed by the statute: notice, objections, and formal publication. Anything less would collapse the distinction between a proposal and a legally operative change.

A permission unlawful on the date of its grant cannot be made lawful by a later administrative endorsement unless the statute expressly permits retrospective validation. The PRTPD Act does not.

This is not mere technicality. It is about institutional integrity. When statutes prescribe procedure, that procedure protects public participation and guards against arbitrariness of the state and its instrumentalities.

Environmental Safeguards Are Preventive, Not Decorative

The case also involved environmental dimensions.

The proposed unit required compliance with:

Prior environmental clearance under the EIA Notification, 2006, and

Siting norms under the Punjab Pollution Control Board’s notification of 2 September 1998, including minimum distances of 300 metres from educational institutions and residential clusters.

The Supreme Court emphasised that environmental clearance is preventive. It must precede construction or preparation of land. Similarly, siting norms must be demonstrably complied with at the threshold—not postponed to the stage of consent to operate.

Where a school and habitations lie in proximity, regulatory satisfaction cannot rest on assumptions about boundary measurements or future compliance. Preventive safeguards are meaningful only if applied before the potentially hazardous exposure occurs.

The Constitutional Turn: Downgrading from “Red” to “Orange”

During the pendency of the appeals, a second development occurred. In January 2025, the Central Pollution Control Board reclassified “stand-alone grinding units without CPP” from the Red category to the Orange category, followed by guidelines relaxing siting safeguards.

The petitioners had also challenged this under Article 32.

The Supreme Court’s reasoning here is particularly significant. It held that while expert bodies enjoy regulatory latitude, judicial restraint ends where constitutional protections begin.

The Supreme Court asked the right question:

Not whether a grinding unit is less polluting than an integrated cement plant, but whether its pollution potential is so low that preventive buffers around schools and habitations can safely be reduced.

Finding the justification inadequate, the Apex Court also quashed the reclassification to the extent it downgraded such units and relaxed safeguards.

In doing so, it explicitly invoked Articles 14 and 21. The right to life includes the right to a clean and healthy environment. A regulatory dilution that weakens preventive protection without proportionate and reasoned justification is arbitrary and constitutionally suspect.

Development Within Constitutional Discipline

What makes the judgment persuasive is its balance. The Bench did not adopt an anti-industry tone. It acknowledged the legitimacy of economic development and industrial growth. Equally, it made clear that the door remains open for regulators to revisit classification and consent frameworks—provided they do so through a fresh exercise that is reasoned, transparent, and scientifically substantiated, and that stays faithful to the precautionary principle and the Constitution’s mandate to protect life, health, and the environment.

But it reminded us of a foundational truth:

Development in a constitutional democracy is conditioned by the rule of law.

Investment, employment generation, or single-window facilitation cannot legitimise a permission that lacks statutory foundation. Nor can sector-level reclassification justify lowering the constitutional floor of environmental protection.

The Apex Court’s message is neither obstructionist nor romantic. It is institutional: planning discipline and preventive safeguards are part of the constitutional architecture of governance.

The Human Element: A 93-Year-Old Litigant and Access to Justice

Amidst the legal doctrine, one detail stands out. A 93-year-old landowner—whose writ petition had been dismissed by the High Court—chose not to surrender. He invoked the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction and succeeded.

This is not merely anecdotal. It underscores three democratic strengths:

Judicial accessibility – Even after losing in the High Court, a citizen can seek constitutional correction.

Substantive review – The Supreme Court did not treat the matter as closed because a High Court had spoken.

Endurance of rights – Age does not diminish constitutional standing.

In an era when environmental disputes are often framed as battles between “development” and “activism”, this case reminds us that they are frequently about ordinary landowners, habitations, and schools seeking adherence to law.

Why This Judgment Matters

For an informed Indian audience, three larger lessons emerge:

Master Plans have binding force. They cannot be informally rewritten through executive approvals.

Ex post facto validation has limits. Illegality cannot be cured by administrative endorsement.

Environmental downgrades are constitutionally reviewable. When preventive safeguards protecting life and health are diluted, Articles 14 and 21 are engaged.

Most importantly, the judgment reaffirms a quiet but powerful principle:

The Constitution is present at the planning desk, in the pollution control office, and in the industrial categorisation file.

And sometimes, it is carried there by a 93-year-old citizen who refuses to give up.

In that sense, this verdict is not merely about zoning or cement grinding units. It is about institutional discipline, environmental prudence, and the enduring vitality of constitutional remedies, involving fundamental rights.

Share The KBS Chronicle