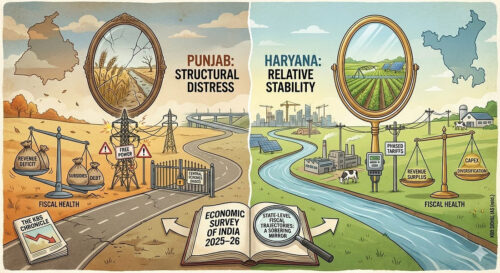

India’s Economic Survey 2025–26 holds up a sobering mirror to Punjab — a state once celebrated as the nation’s breadbasket, now conspicuously absent from key fiscal-health narratives as a success story and instead flagged for structural economic distress. While the Survey chronicles India’s post-pandemic fiscal consolidation and growth acceleration, Punjab’s limited appearances point to deteriorating revenue balances, unsustainable expenditure patterns, and exclusion from central support schemes on account of fiscal fragility. Haryana, by contrast, features in the standard state-level assessments, suggesting relatively stronger fiscal management despite its own pressures.

India’s Economic Survey 2025–26 holds up a sobering mirror to Punjab — a state once celebrated as the nation’s breadbasket, now conspicuously absent from key fiscal-health narratives as a success story and instead flagged for structural economic distress. While the Survey chronicles India’s post-pandemic fiscal consolidation and growth acceleration, Punjab’s limited appearances point to deteriorating revenue balances, unsustainable expenditure patterns, and exclusion from central support schemes on account of fiscal fragility. Haryana, by contrast, features in the standard state-level assessments, suggesting relatively stronger fiscal management despite its own pressures.

This divergence between two neighbouring states with shared agrarian legacies underlines a simple but urgent truth: Punjab needs decisive structural reforms to remain on a sustainable growth trajectory. The Survey’s treatment of Punjab — marked as much by omissions as by inclusions — reads as a warning that business-as-usual approaches will no longer suffice.

Both Punjab and Haryana have witnessed meaningful disinflation alongside the national trend, though the pace and magnitude differ sharply (Economic Survey, p. 219). Punjab’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation declined from 6.08 per cent in FY 2022–23 to 3.27 per cent in FY 2025–26 (April–December), a reduction of nearly 46 per cent. Haryana experienced even sharper disinflation, with CPI falling from 7.51 per cent to 1.61 per cent over the same period — a striking 79 per cent decline.

This moderation has been aided by what the Survey describes as a “Goldilocks combination” in agriculture: favourable monsoons, above-normal reservoir levels, strong kharif harvests, and robust rabi sowing (p. 222). For Punjab and Haryana — major agricultural producers — this has eased food-price pressures. Lower inflation improves real purchasing power for households and reduces cost pressures for firms, creating a more supportive environment for economic activity.

The Survey’s state-level inflation analysis (pp. 218–221) also indicates that both states are now comfortably within the Reserve Bank of India’s tolerance band of 2–6 per cent, reflecting “increasing synchronisation of inflation across States”, with remaining differences mainly driven by local relative-price movements rather than persistent broad-based inflation (p. 219).

Agricultural output: maintaining production levels

Despite structural constraints, both states remain integral to national food security. The Survey notes that India’s foodgrain production is estimated at 3,577.3 lakh metric tonnes in Agricultural Year 2024–25 — up by 254.3 LMT over the previous year (p. 228). While the section does not provide state-wise break-ups, Punjab and Haryana’s historical contributions to wheat and rice procurement remain substantial.

The Survey highlights steady expansion in procurement: between FY 2014–15 and FY 2024–25, wheat procurement rose significantly, as did paddy procurement (p. 254, Chart VI.11). This procurement architecture, through Minimum Support Price (MSP) operations, continues to provide income stability to farmers in both states.

The livestock sector is also flagged as a strong growth area, with Gross Value Added (GVA) rising by nearly 195 per cent between FY15 and FY24, recording a compound annual growth rate of 12.77 per cent at current prices (p. 228). Allied sectors — dairy, poultry, and value-added food chains — remain credible diversification pathways for both Punjab and Haryana.

The Survey’s most damning assessment of Punjab lies in both what it states and what it notably omits. Between FY19 and FY25 (Provisional Actuals), 18 states saw deterioration in revenue balances, with 10 slipping from revenue surplus into revenue deficit (pp. 59–60). Punjab is among those that experienced this adverse transition.

Chart II.10 (p. 60) maps fiscal performance through the revenue receipts to revenue expenditure (RR/RE) ratio — above 1 implies revenue surplus; below 1 indicates revenue deficit. Punjab’s movement into deficit territory is especially alarming because a revenue deficit implies borrowing to fund current consumption, leaving little room for growth-enhancing capital investment.

Even more telling is Punjab’s explicit exclusion from certain analyses. Chart II.13 (p. 63), which examines reliance on Special Assistance to States for Capital Expenditure/Investment (SASCI) against per capita GSDP, carries a clear annotation: “Excludes Goa, Kerala, Mizoram, Punjab and Sikkim.” SASCI provides 50-year interest-free loans to states for capital expenditure. Punjab’s exclusion — and the implied distance from this fiscal support channel — points to a state considered too fiscally fragile for even a scheme designed to stabilise and sustain capex (p. 63).

Haryana’s challenges: less severe, but significant

Haryana is better placed than Punjab, but it is not without stresses. It appears in standard analyses and, as Chart II.10 (p. 60) shows, also experienced some deterioration between FY19 and FY25PA, though it managed to maintain revenue-surplus status.

Haryana’s inflation performance is impressive, yet it began from a higher base than Punjab (7.51 per cent in FY22–23), suggesting greater historical volatility. The Survey’s state-level inflation persistence analysis (Chart V.19, p. 220) indicates that while inflation differentials exist across states, persistence patterns matter — and Haryana’s earlier levels suggest structural demand–supply imbalances that merit attention even amid current moderation.

The unconditional cash-transfer trap

Box II.7 (pp. 64–65) issues a pointed caution on Unconditional Cash Transfers (UCTs) — relevant to both Punjab and Haryana. Aggregate UCT spending is estimated at ₹1.7 lakh crore for FY26, and the number of states implementing such schemes rose more than five-fold between FY23 and FY26. Crucially, “around half of these States [are] estimated to be in revenue deficit” (p. 64).

UCT outlays range from 0.19 per cent to 1.25 per cent of GSDP, and account for 0.68 per cent to 8.26 per cent of total budgetary expenditure across implementing states (p. 64). For a revenue-deficit state such as Punjab, this becomes a high-risk fiscal wager. The Survey’s logic is blunt: either deficits widen — worsening fiscal health — or additional spending crowds out resources for vital infrastructure and social investment (p. 65).

The Survey also cites evidence: a recent NBER meta-analysis covering 115 randomised trials found that while cash transfers can raise short-term consumption, they rarely improve labour supply, agricultural productivity, or long-term income (p. 65). By contrast, capital expenditure — through infrastructure creation and crowding-in private investment — yields more durable improvements in incomes and living standards (p. 65).

Productivity gaps and agricultural stagnation

The Survey’s agricultural productivity discussion reveals structural concerns affecting both states. Chart VI.7 (p. 230) presents rice yields for FY 2023–24 and FY 2024–25. Punjab’s yields remain among the highest (around 4,000 kg/hectare), yet the broader concern is stagnation within a high-input system.

More structurally, Chart V.16 (p. 216) shows the ratio of the manufacturing deflator to the agricultural deflator halving between FY05 and FY25 — from 1.29 to 0.65. Put simply, relative price movement has disadvantaged agriculture over time. For Punjab and Haryana — where agriculture still shapes political economy and fiscal choices — this represents a long-run pressure on relative incomes and incentives (pp. 216–217).

The Survey notes that agriculture can show price rises due to government support and annual guaranteed MSP increases, while manufacturing faces global competition, cost-cutting technologies, and thinner margins (pp. 216–217). The resulting distortions can encourage resource retention in agriculture without necessarily generating sustainable productivity gains.

THE UGLY

Power-sector cross-subsidies: a structural distortion

Box II.3 (pp. 51–52) addresses cross-subsidies in the power sector — especially relevant to Punjab. The Survey explains that cross-subsidisation typically means higher tariffs for industrial and commercial consumers to offset low tariffs for domestic and agricultural users. It notes that in some states, the Average Cost of Supply (ACoS) coverage exceeds the 20 per cent limit specified in the Tariff Policy (p. 51).

Punjab’s power-subsidy burden — particularly free electricity for agriculture — is widely recognised as fiscally draining and economically distortionary, reinforcing water-intensive cropping patterns. The Electricity Amendment Bill, 2025, introduced to address such inefficiencies, mandates that tariffs reflect the cost of supply and requires cross-subsidies paid by industrial users and transport utilities to be fully eliminated within five years (p. 52).

For Punjab, this suggests an unavoidable reckoning: either agricultural tariffs rise (politically difficult), budgetary subsidies expand (fiscally unsustainable), or agricultural practices shift to reduce power intensity (structurally challenging). The Survey recommends a balanced approach through phased tariffs, quotas, and voluntary/category-based exclusions (p. 52) — and Punjab’s delay in confronting this distortion may be its single most damaging structural constraint.

Debt sustainability concerns: the elephant in the room

While the Survey does not provide state-wise debt ratios in the excerpts referenced here, its framework for debt sustainability is clear. It identifies the debt-to-GSDP ratio and the interest payments to revenue receipts (IPRR) ratio as key fiscal-health variables (pp. 72–73). For 28 states combined, debt-to-GDP is placed at 28.1 and IPRR at about 12.6 for FY25PA, while noting “considerable variation” across states (p. 72).

The Survey also warns that persistent revenue deficits or expanding committed expenditures at the state level can influence sovereign borrowing costs because markets price government debt on a consolidated basis (p. 78). Punjab’s fiscal stress, therefore, is not merely a state issue; it can add friction to the wider macro-fiscal environment.

Exclusion from growth opportunities

The most disquieting thread in Punjab’s Survey presence is repeated exclusion from forward-looking fiscal support channels and analytical frames. SASCI exclusion is a prime example. The Survey’s Box II.5 (p. 58) stresses that higher capital expenditure improves infrastructure, reduces transaction costs, crowds in private investment, and supports employment — generating more durable gains in incomes and living standards. It also notes that states that devote larger resources to capital formation tend to record stronger growth outcomes even after controlling for other variables (p. 58).

Punjab’s fiscal trap — revenue deficit, debt burden, and politically committed subsidies/transfers — restricts its capacity for capital expenditure, pushing the state into a vicious cycle: weak fiscal space limits capex; low capex constrains growth; constrained growth worsens fiscal position.

Biofuel policy: unintended consequences

A Survey discussion on biofuels (pp. 234–235) flags an emerging agricultural-policy tension with direct implications for Punjab and Haryana. It notes that maize has grown rapidly in production and cultivated area between FY22 and FY25, with CAGRs of 8.77 per cent and 6.68 per cent respectively, while pulses have seen declines in output and acreage (p. 235). The warning is explicit: pulses and oilseeds are nutritionally and structurally important, yet are slipping down the priority order for cultivators due to incentives (p. 235).

For Punjab and Haryana — both seeking crop diversification away from the paddy–wheat cycle — the danger is that new incentives shift cropping patterns without solving the underlying water-stress and sustainability problem. The Survey captures this as a tension between Aatmanirbharta in energy and Aatmanirbharta in food (p. 235).

COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT: PUNJAB VS HARYANA

Despite shared geography and agrarian legacies, the Survey reflects a widening divergence.

Inflation performance: Haryana’s CPI fell to 1.61 per cent (April–December FY25–26) versus Punjab’s 3.27 per cent (p. 219). The 166-basis-point gap suggests stronger demand–supply balance and, possibly, more effective state-level stabilisation.

Fiscal management: The central distinction is fiscal discipline. Haryana remained in revenue surplus despite some deterioration, whereas Punjab slipped into revenue deficit (p. 60, Chart II.10). This is not merely accounting; it reflects policy choices on expenditure restraint and revenue mobilisation.

Capital expenditure capacity: Haryana’s presence in standard analyses implies retained fiscal space for capex. Punjab’s exclusion from SASCI analysis indicates limited access to a key capex-support channel (p. 63), tightening constraints on growth-enhancing investment.

Agricultural performance and diversification: Both face productivity and sustainability pressures. Yet Haryana arguably has greater flexibility to diversify, while Punjab’s political economy — shaped by entrenched paddy–wheat dependence and power subsidies — makes reform far more difficult.

THE IMPERATIVE FOR DRASTIC REFORMS

The Economic Survey 2025–26’s treatment of Punjab should be read as an urgent signal. The state confronts a multi-dimensional bind: fiscal unsustainability, agricultural stagnation, power-sector distortions, and reduced access to central capital-support mechanisms. Incremental tinkering will not suffice.

Power-sector reform: The Survey’s discussion of the Electricity Amendment Bill, 2025 — with a five-year pathway to eliminate cross-subsidies (p. 52) — offers Punjab a limited window to move to phased tariffs, quotas, solar pumping and micro-irrigation, stronger water governance, and time-bound, transparent income support in place of permanent price distortions.

Fiscal consolidation: Punjab needs simultaneous action on revenue and expenditure: modernised tax administration, credible property-tax reform, user charges aligned to cost recovery, and sensible asset monetisation. On expenditure, it must phase out or strictly means-test populist transfers, protect capital outlay, impose sunset clauses on subsidies, and confront the sustainability of pension commitments.

Agricultural transformation: The Survey’s emphasis on diversification and allied sectors (pp. 227–228, 236–237) offers a roadmap: horticulture expansion, livestock and dairy scaling (with the cited 12.77 per cent CAGR), premium-value crops, stronger Farmer Producer Organisations, and targeted agri-tech adoption to lift productivity while conserving water.

Institutional reforms: Punjab’s economic constraints are ultimately governance constraints: depoliticising key economic decisions, strengthening planning and statistical capacity, engaging strategically with the Sixteenth Finance Commission, and using public–private partnerships to leverage private capital and expertise.

Haryana, while stronger than Punjab, should not mistake relative stability for immunity. It must sustain inflation control, avoid fiscally corrosive transfer expansions, deepen capex, diversify into services and high-value manufacturing, and invest more deliberately in human capital.

THE PATH FORWARD

The Economic Survey 2025–26 presents an unflinching portrait of India’s state-level fiscal trajectories. For Punjab, the verdict is sobering: a state in fiscal distress, constrained capital capacity, and structurally distorted incentives — particularly in power and agriculture. Haryana is better placed, yet still faces meaningful risks if it succumbs to complacency or populist drift.

The divergence between these neighbouring states reinforces a hard truth: economic outcomes reflect policy choices. Punjab’s predicament is not a geographic inevitability; it is the cumulative product of decisions that have prioritised short-term political convenience over long-term sustainability.

The Survey provides both diagnostic clarity and policy direction. What remains is political courage — to act early, deliberately, and transparently — before fiscal arithmetic imposes far harsher adjustments.