Budha Nala, once a natural freshwater stream flowing through Ludhiana, has over decades been reduced to a heavily polluted drain carrying industrial effluents, untreated sewage, and solid waste into the Sutlej River. What was historically a life-supporting water channel has today become a symbol of environmental failure, regulatory weakness, and unchecked urban-industrial growth. The pollution of Budha Nala is not a sudden crisis but the result of long-term neglect involving government agencies, industries, and society at large.

Budha Nala, once a natural freshwater stream flowing through Ludhiana, has over decades been reduced to a heavily polluted drain carrying industrial effluents, untreated sewage, and solid waste into the Sutlej River. What was historically a life-supporting water channel has today become a symbol of environmental failure, regulatory weakness, and unchecked urban-industrial growth. The pollution of Budha Nala is not a sudden crisis but the result of long-term neglect involving government agencies, industries, and society at large.

Ludhiana, Punjab’s largest industrial hub, expanded rapidly without matching investments in environmental safeguards. Textile dyeing units, electroplating factories, bicycle and hosiery industries grew along the banks of Budha Nala, using it as the most convenient disposal route for liquid waste. Over time, the drain lost its self-purifying capacity and turned into a toxic channel carrying chemicals, dyes, heavy metals, oils, and sewage.

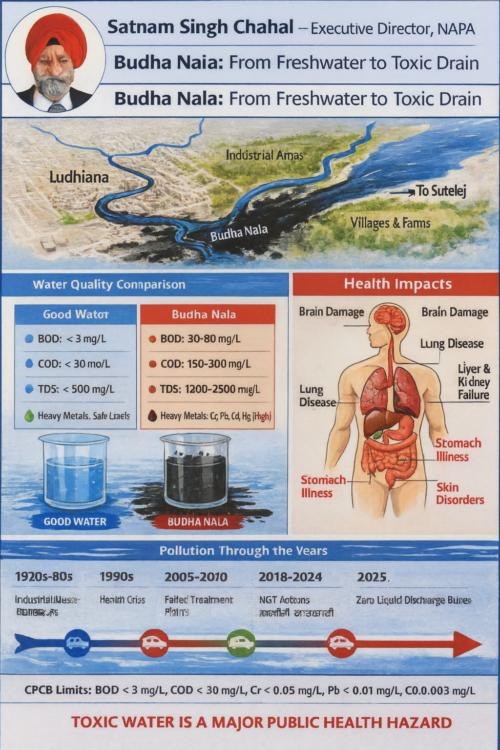

Scientific assessments and regulatory reports consistently show that Budha Nala is among the most polluted water bodies in North India. Water quality parameters far exceed permissible limits set by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB). Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD), which indicates organic pollution, has frequently been recorded at 30–80 mg/L, while the acceptable limit for surface water is 3 mg/L. Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), reflecting chemical contamination, often ranges between 150–300 mg/L, compared to a safe limit of 30 mg/L. These values indicate severe organic and chemical loading, making the water biologically dead in many stretches.

Heavy metals such as chromium, lead, nickel, cadmium, and mercury—commonly used in dyeing, electroplating, and metal industries—have been detected in both water and sediments of Budha Nala. These toxins accumulate in soil and groundwater, posing long-term health risks. Approximately 90–95% of Ludhiana’s untreated sewage, estimated at 300–400 million litres per day (MLD), eventually finds its way into Budha Nala, either directly or through connected drains. Sewage treatment plants (STPs), where present, often operate below capacity or fail to meet discharge standards.

The pollution of Budha Nala has far-reaching consequences beyond the city limits of Ludhiana. As the drain merges with the Sutlej River, contamination spreads downstream, affecting irrigation, drinking water sources, and aquatic ecosystems. Groundwater samples collected from areas near Budha Nala have shown elevated levels of heavy metals, making hand pumps and bore wells unsafe for consumption. Farmers using polluted water for irrigation face soil degradation and crop contamination, increasing health risks through the food chain. Residents living along the drain report high incidences of skin diseases, respiratory problems, stomach ailments, and suspected cancer cases. The stagnant, foul-smelling water also creates breeding grounds for mosquitoes, worsening public health conditions.

The Punjab Pollution Control Board is the statutory authority responsible for preventing and controlling water pollution in the state. On paper, PPCB has powers to issue notices, impose penalties, close polluting units, and mandate treatment systems. In practice, its role in controlling Budha Nala pollution has been widely criticized as reactive and inconsistent. PPCB has repeatedly issued directions to industries to install Effluent Treatment Plants (ETPs) and has mandated Zero Liquid Discharge (ZLD) for dyeing units within Ludhiana. It has also monitored Common Effluent Treatment Plants (CETPs) meant to treat waste from clusters of industries.

However, enforcement gaps remain significant. Many small and scattered industrial units operate without proper consent or bypass treatment systems during night hours to reduce costs. Inspections are often infrequent, and penalties are insufficient to deter violations. Reports submitted to the National Green Tribunal (NGT) have repeatedly highlighted non-compliance even at approved treatment facilities.

Industries in Ludhiana bear a major share of responsibility for Budha Nala’s degradation. While large units may have treatment systems, smaller industries often lack the financial or technical capacity and resort to illegal discharges. Industrial associations have at times resisted relocation or stricter norms, citing employment and economic concerns. Yet environmental compliance is not optional but a legal and moral obligation. Cleaner production methods, reuse of treated water, and strict adherence to ZLD norms are essential if industrial growth is to coexist with environmental safety.

The general public is both a victim and a stakeholder in the Budha Nala crisis. Domestic sewage, plastic waste, and solid garbage dumped into drains contribute significantly to pollution. Poor waste segregation and illegal dumping worsen the load on the already stressed system. At the same time, civil society movements have played a crucial role in keeping the issue alive. Environmental activists, local residents, and organizations have organized protests, awareness campaigns, and legal interventions demanding accountability. Public pressure has often forced authorities to acknowledge the scale of the problem and take corrective steps, even if progress remains slow.

Budha Nala in Ludhiana represents one of the most severe cases of urban and industrial water pollution in Punjab. What was once a natural freshwater stream has gradually been transformed into a carrier of untreated industrial effluents and municipal sewage. The contamination of Budha Nala is not only visible in its dark color and foul odor but is scientifically evident in its chemical composition, which stands in sharp contrast to the parameters of clean and safe water. This toxic transformation has had serious and long-lasting consequences for human health, animal life, agriculture, and the surrounding ecosystem.

From a chemical perspective, Budha Nala water contains extremely high concentrations of organic pollutants, toxic chemicals, and heavy metals. Tests conducted by regulatory agencies show that the Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) of Budha Nala water commonly ranges between 30 and 80 milligrams per litre, while clean surface water should not exceed 3 milligrams per litre. High BOD indicates excessive organic waste, which consumes dissolved oxygen and makes the water incapable of supporting aquatic life. In comparison, good-quality river water maintains sufficient oxygen levels to support fish, microorganisms, and natural self-purification processes.

Similarly, the Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) of Budha Nala often ranges from 150 to 300 milligrams per litre, compared to the acceptable limit of 30 milligrams per litre in clean water. COD measures the presence of chemically oxidizable pollutants, including industrial chemicals and dyes. Elevated COD levels confirm the presence of toxic substances that are resistant to natural degradation. Clean water, by contrast, has low COD values, reflecting minimal chemical contamination and safer conditions for biological life.

One of the most alarming aspects of Budha Nala pollution is the presence of heavy metals. Chemical analysis frequently detects chromium, lead, nickel, cadmium, and mercury in concentrations several times higher than permissible limits. Chromium, commonly used in textile dyeing and electroplating industries, is known to cause skin ulcers, respiratory problems, and cancer with prolonged exposure. Lead affects the nervous system, particularly in children, causing developmental disorders, learning disabilities, and anemia. Cadmium and mercury damage kidneys, liver, and the reproductive system. In clean water sources, these metals are either absent or present only in trace amounts well below harmful thresholds.

Budha Nala also carries excessive levels of Total Dissolved Solids (TDS), often exceeding 1,200 to 2,500 milligrams per litre, while safe drinking water standards recommend levels below 500 milligrams per litre. High TDS alters the taste of water, damages crops, and increases the salinity of soil. Clean water maintains balanced mineral content essential for human consumption, agriculture, and livestock health.

The chemical toxicity of Budha Nala water has direct and indirect impacts on human health. Communities living near the drain or relying on contaminated groundwater face higher incidences of skin diseases, gastrointestinal disorders, respiratory illnesses, and long-term chronic conditions. Prolonged exposure to heavy metals through drinking water or food grown with polluted irrigation water increases the risk of cancers, kidney failure, hormonal imbalance, and immune system suppression. Children and elderly populations are particularly vulnerable, as their bodies absorb toxins more readily and recover more slowly.

Animal health has been equally affected. Livestock drinking water contaminated by Budha Nala suffer from reduced milk production, reproductive disorders, organ damage, and premature death. Veterinary reports from polluted regions indicate higher rates of digestive diseases and weakened immunity in cattle and buffaloes. Aquatic life in Budha Nala has almost completely collapsed; fish cannot survive in oxygen-depleted, chemically toxic water, and the natural food chain has been destroyed. Birds and stray animals feeding near the drain are also exposed to toxins, leading to bioaccumulation and long-term ecological imbalance.

Agriculture in areas surrounding Budha Nala has suffered due to the use of polluted water for irrigation. Toxic metals accumulate in soil and crops, particularly vegetables and fodder, entering the human food chain. Over time, soil fertility declines, crop yields reduce, and the land becomes increasingly unsuitable for safe farming. Clean water, by contrast, supports healthy soil microorganisms, crop nutrition, and sustainable agricultural productivity.

Beyond chemistry and health, Budha Nala symbolizes a broader governance and social failure. Despite the presence of environmental laws and regulatory bodies such as the Punjab Pollution Control Board, weak enforcement and delayed corrective measures have allowed pollution to persist for decades. Industrial growth has been prioritized over environmental safety, while inadequate sewage treatment infrastructure has compounded the problem. The general public, too, has contributed through improper waste disposal and lack of sustained civic pressure.

In conclusion, the contrast between the chemical composition of Budha Nala water and clean water clearly explains why this drain has become a serious threat to human and animal life. Budha Nala is not merely polluted; it is chemically toxic. Its restoration is not only an environmental necessity but a public health emergency. Without strict enforcement of pollution control laws, responsible industrial practices, upgraded treatment infrastructure, and active public participation, the damage will continue to spread silently through water, soil, food, and living beings. Clean water sustains life; polluted water, as seen in Budha Nala, slowly destroys it.