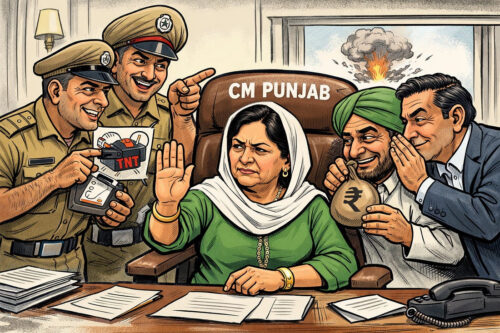

Punjab rarely hears a political statement as disturbing—and as necessary—as the recent revelation by former Chief Minister of Punjab, Mrs Rajinder Kaur Bhattal. She disclosed that before the 1997 Assembly elections, she was approached with a chilling proposal: allow bomb blasts to create fear, polarise voters, and convert chaos into electoral advantage.

Punjab rarely hears a political statement as disturbing—and as necessary—as the recent revelation by former Chief Minister of Punjab, Mrs Rajinder Kaur Bhattal. She disclosed that before the 1997 Assembly elections, she was approached with a chilling proposal: allow bomb blasts to create fear, polarise voters, and convert chaos into electoral advantage.

Bhattal refused. That refusal matters. And the fact that she chose to reveal it even after nearly 30 years makes it deeply relevant today.

In a political culture where winning is often treated as the ultimate virtue, she chose Punjab over party, conscience over command, and democracy over getting re-elected. She did not just reject an immoral plan; she rejected the very idea that terror could ever be a political tool. By later speaking about it publicly, she took a second, even braver step—exposing a dark truth that many would have preferred to remain buried.

For that, she deserves appreciation.

However, Punjab cannot stop at appreciation alone.

One Refusal Raises an Uncomfortable Question

Bhattal’s statement forces a question the state can no longer avoid: if one leader refused, how many others may have agreed? And to what level were such agreements made—purely political, or deeply rooted in a monetary nexus as well?

Such proposals do not emerge in isolation. They arise only in systems where police officers believe political protection is assured, and politicians believe violence can be “managed.” This is the essence of the political–police nexus—a quiet, mutually beneficial arrangement where power and force feed each other. Quid-Pro at its best!

Punjab’s own history explains how this nexus took root. During the militancy years of the 1980s and early 1990s, extraordinary powers were given to the police to fight terrorism. Those years were brutal, and the challenges were real. Terrorism was defeated; however, the extraordinary policing architecture was never fully dismantled—it merely changed its form.

Instead of returning to normal democratic oversight, unchecked power became normalised. Promotions, postings, and protection increasingly depended on political loyalty rather than professionalism. Politicians, in turn, found it convenient to use police muscle to manage opponents, influence elections, silence trouble, and even partner for monetary gains.

Although militancy ended, this nexus did not. It simply evolved.

From State Power to Outsourced Violence

Today, Punjab is battling organised gangs, extortion networks, drug syndicates, and foreign-based criminals. These gangs do not operate only on the strength of weapons. They survive because of information leaks, selective enforcement, and political indifference.

The old model—direct coercion by the state—has evolved into a new one: outsourced violence. Gangsters do what the system no longer wants to do openly. Politicians maintain distance. Accountability evaporates.

The Maur bomb blast, just before the 2017 Assembly polls, remains untraced till date. This is not an isolated failure. This is why high-profile crimes remain unsolved. This is why investigations slow down after elections. This is why fear resurfaces at politically sensitive moments.

The nexus adapts very fast, and that is precisely why it survives.

Why Naming Names Is Essential

Bhattal has done what few leaders have dared to do: she broke the silence. But truth cannot stop halfway.

Punjab has a right to know:

· which police officers made this proposal,

· which political intermediaries were involved,

· and who believed bomb blasts were an acceptable election strategy.

Naming names is not about revenge or reopening old wounds. It is about ensuring such ideas never surface again. Without accountability, the message goes out that even the most dangerous proposals carry no consequences.

The Nexus Must Be Broken — But Who Will Dare?

This brings us to the most difficult question of all.

Who in Punjab today has the political commitment to do what Bhattal did—and go further? Or, in other words, does any leader have the will to stand for Punjab rather than merely for their party? Who is willing to rise above party loyalties, high-command diktats, and electoral arithmetic?

Who will confront police misuse, political complicity, and criminal partnerships—even if it costs power?

Although illegitimately offered power and money make it easier for politicians to regain and retain office, the long-term cost is devastating for Punjab.

Such leadership is rare. However, without it, Punjab will remain trapped in a cycle where violence mutates but never disappears. Bhattal proved that refusal was possible. Her disclosure proves that silence, even today, is a choice.

Now Punjab must demand the final step: full truth, full accountability, and a clear dismantling of the political–police nexus.

Because democracy does not collapse in one blast.

It collapses when those who planned, proposed, or protected such ideas are never named.