The Lakhimpur Kheri case—already a byword for public anguish and procedural drift—has taken a combustible turn. Acting on directions issued by the Supreme Court, the Uttar Pradesh Police have registered a fresh FIR against former Union Minister Ajay Mishra ‘Teni’, his son Ashish Mishra, and two others for allegedly attempting to influence a key witness. The complaint comes from Baljinder Singh, a prosecution witness who says he faced both bribery and intimidation to make him resile from his testimony in the Tikunia violence case.

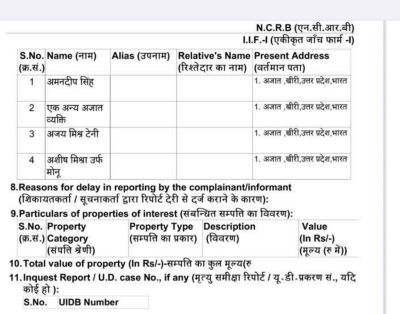

The Lakhimpur Kheri case—already a byword for public anguish and procedural drift—has taken a combustible turn. Acting on directions issued by the Supreme Court, the Uttar Pradesh Police have registered a fresh FIR against former Union Minister Ajay Mishra ‘Teni’, his son Ashish Mishra, and two others for allegedly attempting to influence a key witness. The complaint comes from Baljinder Singh, a prosecution witness who says he faced both bribery and intimidation to make him resile from his testimony in the Tikunia violence case.

Baljinder’s account is chilling in its ordinariness: on 15 August 2023, Amandeep Singh—identified by him as the husband of the Nighasan Block Pramukh—allegedly turned up at his house with a demand that he alter his statement. The inducement, he says, was ₹1 lakh; the deterrent was a threat of “dire consequences” if he chose to testify. What followed was a spiral familiar to anyone who has watched India’s witness-protection promises fray in practice: the witness left his home for his in-laws’ residence in Shardanagar; the emissary allegedly followed him there on the eve of his scheduled deposition on 16 October 2023; fear forced him to lease out his land and relocate to Punjab. The allegation is not merely that a supporter tried to get to him—it is that the attempt was under the shadow of influence attributed to Ajay Mishra and his son.

The Supreme Court’s Hard Look at Soft-Pedalling

The Supreme Court has treated these allegations with unusual urgency. A bench led by Justices Surya Kant, Ujjal Bhuyan and N. Kotiswar Singh called it “imperative” that claims of witness influence be investigated, and expressed dissatisfaction with the state police response. The Court underlined a common-sense principle too often ignored: if a complainant seems reluctant to come forward, a senior officer can and should go to the complainant to verify the grievance. In other words, the system must not hide behind procedural passivity when the allegation itself is that procedure is being subverted.

Bail Operational: Absolute, but Hedged with Conditions

Against that backdrop stands the current bail position of Ashish Mishra. The Supreme Court confirmed and made absolute his interim bail on 22 July 2024, but ring-fenced it with strict conditions. He may reside in Delhi or Lucknow; he cannot enter Uttar Pradesh except for trial dates; and, since May 2025, he may visit Lakhimpur Kheri once every weekend—from Saturday evening to Sunday—to meet family, with a clear prohibition on public meetings or political activity during those visits. There is, crucially, an express bar on influencing witnesses. The Court has said it in plain terms: any attempt to tamper with evidence or intimidate witnesses will invite cancellation of bail.

Over the past year, petitions pressing for cancellation have met a high evidentiary bar. In March 2025, after a state report found no material breach that could survive scrutiny, the Supreme Court declined to revoke bail. The message was consistent: liberty stands unless clear, cogent new material shows that liberty is being abused.

The Trial: A Marathon Measured in Years, Not Months

Inside the courtroom, the case moves at the speed of a crowded docket. The prosecution lists 208 witnesses. By late 2025, barely around twenty-odd had been examined. Another twenty from the original list have been dropped. The record is voluminous—171 documents and 27 forensic reports—including material relating to four seized weapons, among them a rifle and a revolver attributed to Ashish Mishra; forensic findings record evidence of firing. The picture that emerges is of a trial with all the complexity of a major riot-cum-homicide case and all the inertia of a burdened sessions court.

The last few months have seen jagged progress. Five witnesses backed away, prompting discharge applications to prune the list. The 22nd prosecution witness—Dilbagh Singh of the Bharatiya Kisan Union—has deposed, with cross-examination spilling over multiple dates. The trial judge’s sober assessment—that in the normal course such a matter could take up to five years—now reads less like pessimism and more like prophecy.

Tikunia, 3 October 2021: A Day That Rewrote West U.P.’s Political Weather

The violence at Tikunia on 3 October 2021 altered the political imagination of western Uttar Pradesh. As farmers mobilised to protest the then Deputy Chief Minister Keshav Prasad Maurya’s visit, chaos unspooled into carnage. An SUV—allegedly with Ashish Mishra aboard—ploughed into protesters, leaving four farmers dead. A journalist was also killed. Fury erupted, and in the aftermath three men from the BJP convoy—a driver and two party workers—were lynched by the crowd. The law’s response bifurcated along that fact pattern: FIR No. 219, lodged by Jagjeet Singh, named Ashish Mishra as prime accused for the mowing-down deaths; FIR No. 220 captured the lynching case as a cross-version.

That duality has shadowed the proceedings since. The State must prosecute both strands with fairness; the Court must insulate both trials from street pressure and political heat; and the public must hold its nerve while grief hardens into a demand for accountability.

The New FIR’s Legal Charge: From Allegation to Admissible Material

Where, then, does the fresh FIR on alleged witness intimidation fit into the bail matrix? The answer lies in a simple, settled test. Bail once granted is not lightly withdrawn—but it can be if supervening circumstances show that the accused is misusing liberty to derail the trial. A live allegation of threats or inducement aimed at a prosecution witness goes to the heart of that test. If the investigation throws up credible, contemporaneous evidence—phone records, location data, statements that interlock, recoveries that corroborate—the FIR can transform from mere accusation into “new material”. And “new material” is exactly what courts look for when asked to cancel bail that has previously survived challenge.

It bears recalling that the Supreme Court has already put a spotlight on witness safety in this very case. When the country’s highest court exhorts the police to step beyond desk-bound excuses, it is signalling that the preservation of testimony is as critical as the preservation of liberty. Should the present investigation validate Baljinder’s account—offers of money, repeat visits across locations, explicit references to the named accused—the balance will tilt. The same bail order that protects an accused’s freedom also contains the seed of its own recall: the non-negotiable condition against influencing witnesses.

Witness Protection: The Promise India Keeps Breaking

Strip the law of its Latin, and a grim social truth remains: witnesses in India are dangerously alone. The paper architecture of “witness protection” rarely becomes a real perimeter of safety. Baljinder’s trajectory—home to in-laws’ house to a different state—reads like an improvised survival plan, not an institutional one. For every witness who stands firm, another will calculate the risks to family and livelihood and step back. Each withdrawal is not only a private capitulation; it is an injury to the public’s case. And in countryside districts like Lakhimpur Kheri, where everybody knows everybody, the line between social pressure and unlawful intimidation is thin and frequently crossed.

Farmers’ Memory, Public Patience

The farmers’ unions of western Uttar Pradesh have long memories. Tikunia is not just a case in court; it is a story told nightly in village chaupals and weekly at union baithaks. The solidarity that surged during the farm law protests now buttresses the families of the dead. For them, the courtroom’s glacial pace feels indistinguishable from injustice. Yet they continue to show up—at hearings, at anniversaries, at sit-ins—pressing the State to keep its promise: that justice, even if delayed, will not be denied.

The Road Ahead

This new FIR is more than a headline. Properly investigated, it could furnish the supervening material courts require to reconsider liberty that is being used as a weapon against truth. Improperly handled, it will become one more data point in the long ledger of why serious criminal trials collapse in India.

And so the uncomfortable conclusion, spoken plainly. This fresh case of alleged witness intimidation could be a new and valid ground for cancelling Ashish Mishra’s bail. Yet the justice system remains slow—painfully, publicly slow. In a matter where eight people were mauled to death in broad daylight, it is realistic to say the trial will take at least five more years to finish. So much for the due process of law, where the entire pressure of the farmers’ community in western Uttar Pradesh stands behind the victims and their families, still waiting for justice that feels ever just out of reach.