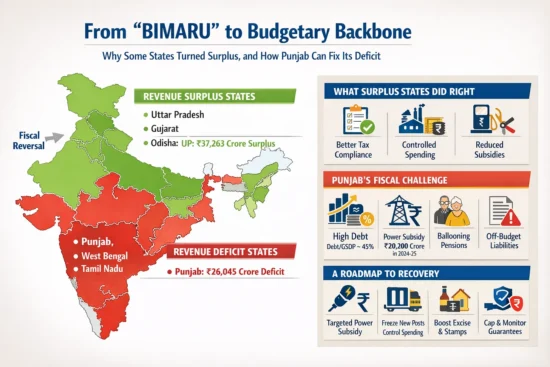

There is a quiet fiscal story unfolding in India—quiet because it does not lend itself to slogans, yet consequential because it will shape the quality of governance for the next decade.States—Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh—once casually dismissed as “BIMARU” are now posting revenue surpluses. At the same time, a few states long assumed to be administratively stronger—and, in Punjab’s case, historically better-off—are struggling with persistent revenue deficits.

There is a quiet fiscal story unfolding in India—quiet because it does not lend itself to slogans, yet consequential because it will shape the quality of governance for the next decade.States—Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh—once casually dismissed as “BIMARU” are now posting revenue surpluses. At the same time, a few states long assumed to be administratively stronger—and, in Punjab’s case, historically better-off—are struggling with persistent revenue deficits.

This is not a moral tale about “good” and “bad” states. Nor is it an argument for austerity. It is a practical reminder that in the post-GST world, fiscal outcomes depend increasingly on governance choices, administrative capacity, and the courage to correct recurring policy distortions—especially those that convert welfare into open-ended entitlements.

The fiscal world after GST: what changed, what didn’t

GST altered the plumbing of state revenues.

SGST became the biggest own-tax head, but states have limited room to change rates; the GST Council sets the broad rate structure.

What states can influence is compliance, enforcement, and administration—in other words, the quality of the tax system.

States still retain powerful non-GST levers: liquor excise, VAT on petroleum products, and stamp duty & registration.

The bigger shock arrived when GST compensation ended in June 2022. Many states had grown accustomed to a cushion. Once it ended, the divergence began: some states adapted quickly; others did not.

A reversal hiding in plain sight

Consider one headline number: Uttar Pradesh recorded the largest revenue surplus in 2022–23 (Accounts): ₹37,263 crore.

Contrast that with Punjab, which recorded a revenue deficit in 2022–23 (Accounts): ₹26,045 crore, with stress continuing through subsequent RE/BE cycles.

Numbers do not explain themselves. But they do force a question: What did some states do differently?

Why “BIMARU” states surprised—and why it matters

Three factors seem to have converged.

1) Compliance, not rate hikes, became the differentiator

With limited discretion on GST rates, states that invested in data-led enforcement and tighter administration gained ground. In a regime where you cannot easily “raise rates”, collection efficiency becomes the edge.

2) They contained “committed expenditure”

Salaries, pensions, and interest payments dominate state budgets. Once these heads expand uncontrollably, the revenue account collapses and borrowing turns into a routine way of life.

States that kept committed expenditure manageable created room for both stability and growth.

3) They pivoted after compensation ended

When the compensation cushion went away, better-performing states leaned harder on what they could still control—excise, stamps, fuel VAT—and they tightened subsidy frameworks.

A closer look: the Uttar Pradesh template (in broad terms)

Uttar Pradesh’s surplus appears to have been driven not by miracles, but by administrative seriousness.

Liquor excise behaved like a workhorse: tighter enforcement, technology, leak-proofing, and better control over a high-yield revenue line.

Stamp and registration collections benefited from digitisation, faster transactions, and a “volume over rate” approach.

Madhya Pradesh presents a steadier story: less dramatic, more incremental, but still illustrating that fiscal repair is possible without grandstanding.

The takeaway is not that Punjab must copy UP. It is that Punjab must relearn the importance of disciplined administration and targeted policy design.

Punjab’s bind: where the real stress lies

Punjab’s problem is not merely low revenue. It is structural.

Persistent revenue deficits mean Punjab borrows not only for development but also, indirectly, to fund routine expenditure.

High debt implies high interest costs, reducing flexibility even further.

Large and recurring subsidies—especially power subsidy—have become fiscally destabilising when structured as broad entitlements rather than sharply targeted protection.

A single number captures the issue: Punjab’s power subsidy has been around ₹20,200 crore in 2024–25.

That is not merely a budget line. It is the fiscal equivalent of a slow leak that eventually floods the entire house.

The reform question: can Punjab repair without hurting ordinary households?

Yes—but only if we stop treating reform as a synonym for cruelty.

Punjab does not need austerity. Punjab needs smart sequencing and honest targeting.

Here is a practical five-part pathway—spread over two to three budgets—to restore the revenue account while protecting growth and dignity.

A five-part pathway back to fiscal health

1) Treat power subsidy as social policy—not tariff policy

A welfare state must protect the vulnerable. But universalised subsidies often end up protecting inefficiency and rent-seeking.

The direction should be:

A lifeline level of support (especially for the genuinely vulnerable),

A shift toward targeted DBT for subsidy delivery,

Gradual tapering beyond basic consumption,

Efficiency-linked conditions where appropriate.

Even an indicative 25% rationalisation could potentially free up around ₹5,000 crore per year—enough to meaningfully alter fiscal space.

2) Stabilise committed expenditure

Punjab must slow the growth of salaries and pensions through:

a pause on net additions to staffing (while allowing attrition),

automation and process reform,

and prudent pension design based on actuarial reality—without introducing new, unfunded liabilities.

3) Make guarantees and off-budget exposures transparent and priced

Guarantees cannot be free. They must be capped, risk-priced, and monitored, with a Guarantee Redemption Fund and clear dashboards for contingent liabilities.

4) Improve revenues without headline tax hikes

Punjab can do better on:

liquor excise (where governance and enforcement matter enormously),

stamps & registration (where digitisation and transaction throughput can deliver),

and selected non-tax revenues / user charges where feasible.

The principle is simple: do not chase citizens; chase leakages.

5) Borrow for growth, not to fund routine consumption

Borrowing is not immoral; misuse is. Punjab must ring-fence borrowing for capex and productivity-enhancing investment, and use long-tenor central capex windows for structural reforms—especially those that permanently reduce the subsidy bill.

A realistic “two-year scoreboard”

In my view, reform becomes credible when it is measurable.

A practical scoreboard for Punjab would include:

Year 1: DBT pilots and rollout design; guarantee-fee framework; excise roadmap; stamp/registration reforms; a committed-expenditure stabilisation plan.

Year 2: measurable reduction in the subsidy bill; measurable improvement in excise and stamp collections through administration; movement toward primary revenue balance; protection of productive capital spending.

A request to readers—especially Punjabis worldwide

This is not a partisan argument. It is a governance argument.

If you are a policymaker, administrator, entrepreneur, academic, or a concerned Punjabi citizen—your critique will make this stronger.

Which steps are politically and administratively feasible in Punjab over the next 24 months?

What design features would make subsidy reform fair, durable, and socially protective?

How do we ensure reform is not reversed at the first ele