As India celebrates Republic Day with familiar grandeur on January 26, 2026, Punjab marks a far quieter but far heavier milestone: sixty years of the second partition. On 1 November 1966, Punjab was not merely reorganised. It was politically and economically castrated.

As India celebrates Republic Day with familiar grandeur on January 26, 2026, Punjab marks a far quieter but far heavier milestone: sixty years of the second partition. On 1 November 1966, Punjab was not merely reorganised. It was politically and economically castrated.

What was presented as a linguistic adjustment was, in reality, a carefully engineered act of religious and political consolidation, driven by narrow thinking and short-term power games. The damage caused then explains almost every major crisis Punjab faces today.

The first partition of Punjab in 1947 was savage and visible. Blood flowed, families were torn apart, and half of historic Punjab was lost. The second partition was done with files, commissions and parliamentary acts. No trains burned, but this time what was massacred was Punjab’s political weight, territorial scale, economic strength and strategic depth. The injury was quieter, but permanent.

Before 1966, Punjab was a giant. It stretched from the outskirts of Delhi to the hills of Kullu and beyond, commanding rivers, canals, institutions and influence. That large geography translated into political weight in Delhi and economic diversity on the ground.

Even after the trauma of 1947, East Punjab was wounded but still substantial. It could still rebuild. 1966 ensured it never fully could. The vast map of the empire of Maharaja Ranjit Singh was once divided by the British and the second slicing was pushed by our own.

Black symbolizes resentment

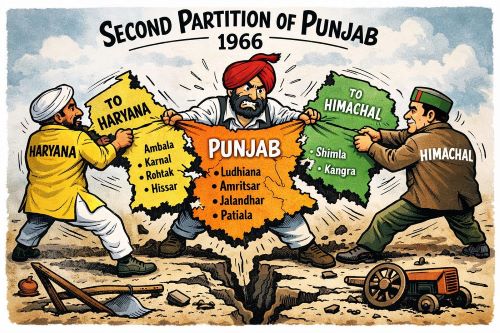

The creation of Punjabi Suba more accurately, a “Subi” reduced Punjab to a compact, inward-looking state. Haryana was carved out, hill areas handed to Himachal Pradesh, and Chandigarh built on Punjabi land as compensation for the loss of Lahore was turned into a Union Territory and a so-called “shared” capital. Punjab paid the price three times over: territory lost, capital snatched, waters disputed.

The political impact was devastating. In a federal democracy, numbers matter. A larger Punjab once sent over twenty two MPs to Parliament. Today, Punjab sends just 13. That single fact explains Punjab’s declining bargaining power on everything, from river waters to industrial policy, from central allocations to national decision-making. Fewer MPs mean fewer committee seats, fewer ministers, and less leverage. Punjab’s voice in Delhi was reduced from assertive to begging and apologetic. This was not accidental.

Was this really about language? Hardly.

The Punjabi Suba agitation, led primarily by the Shiromani Akali Dal, is often described as a linguistic movement. That is only half the truth. Language was the banner; religious consolidation was the subtext. The objective was to create a Sikh-majority state where political power could be exercised without dependence on broader coalitions; essentially, a state designed for electoral convenience, not economic viability.

The Congress, for its own narrow electoral calculations, willingly played along, pushing Hindu-dominated areas into Haryana and weakening a potential rival state. Many Hindus, though culturally and linguistically Punjabi, were nudged to declare Hindi as their mother tongue. What was officially a linguistic division quietly became a religious one.

Ironically, even this objective failed. Despite creating a Sikh-majority state, the Akalis rarely ruled alone and repeatedly depended on alliances. Punjab, meanwhile, was left permanently weakened—a double loss.

The consequences unfolded steadily.

Punjab was locked into agriculture. The Green Revolution brought short-term prosperity but trapped the state in a paddy–wheat cycle that drained groundwater, damaged soil and narrowed employment options. Industrialisation never took off at scale. Border-state status, loss of urban-industrial belts, and lack of sustained central support ensured Punjab remained farm-heavy while Haryana raced ahead in manufacturing, services and NCR-linked growth. A simple comparison of GST collections between Haryana and Punjab tells the story better than any speech. Haryana’s GST collection is 5 times that of Punjab.

This is why unemployment defines Punjab’s youth today. Highly educated young men and women see no future beyond farming or migration. Canada, Australia and Europe have become escape routes, not dreams. A state that once attracted people now exports its youth. This is not coincidence. It is the structural outcome of 1966 and derivative of the narrow political thinking of those days.

Water disputes are another direct inheritance. Rivers that naturally flow through Punjab became instruments of political coercion. The SYL canal controversy, decades of litigation, and repeated attempts to extract water from a state with collapsing aquifers are rooted in the faulty water arrangements imposed after reorganisation. Punjab bears the ecological cost of feeding the nation but is denied sovereign control over its rivers. No state can remain stable when its lifeline is perpetually contested.

Chandigarh remains the most visible betrayal. A capital built by Punjab, on Punjabi land, was taken away administratively. Shared capitals are federal absurdities. Chandigarh’s status is a daily reminder that Punjab was never trusted with full authority over its own affairs.

Then came the darkest chapter: the black decade of terrorism, almost after 10 years when Punjab saw naxalism led violent phase.

Militancy in the 1980s did not arise in a vacuum. It fed on unresolved grievances, over Chandigarh, water, autonomy, unemployment and political humiliation. A generation of frustrated rural youth, products of an unequal Green Revolution and shrinking opportunities, became vulnerable to radical narratives. The state responded with repression, deepening alienation. Punjab paid with over 20,000 lives, institutional breakdown and a long-term trust deficit with the Indian state.

Even today, the psychological residue remains.

The perpetual phrase “Panth in Khatra” also emerged from the same political paranoia responsible for 1966. It was shaped by repeated political betrayals—1947, then 1966, and many after. Ironically, the very attempt to create security through religious consolidation produced greater insecurity, not less. A small, inward-looking state is easier to marginalise, not protect.

Every major problem Punjab faces today—

• chronic unemployment

• economic stagnation

• lack of industrialisation

• over-dependence on agriculture

• water wars and the SYL

• demographic anxiety

• the legacy of terrorism

• and a persistent sense of political injustice

—can be traced, directly or indirectly, to the narrow and shallow political thinking of 1966.

This is why the 60th anniversary of Punjabi Suba cannot be reduced to token seminars or nostalgic speeches. It must be remembered honestly—as a political betrayal, not just a historical blunder.

The Aam Aadmi Party government has a historic responsibility. If AAP truly claims to practice a new kind of politics, it must tell the uncomfortable truth: that linguistic justice was achieved at the cost of political and economic justice; that Punjab was deliberately weakened to serve short-term electoral interests.

Remembering the second partition is not about reopening old wounds. It is about diagnosing the chronic disease correctly. No state can recover without understanding how it was crippled.

AAP should use this 60th year to educate a generation that does not know this history. Link past decisions to present crises. And move from remembrance to action: assert riparian rights, demand a fair resolution of Chandigarh, push aggressive industrialisation, and rebuild Punjab’s political confidence at the national level with responsible leadership.

Punjab fed India when India was hungry. Punjab defended India when borders burned. It does not deserve a future defined by shrinking relevance and permanent grievances.

Sixty years later, the truth must finally be spoken aloud:

1966 did not empower Punjab. It diminished it. Should it be remembered as a Black day in History?