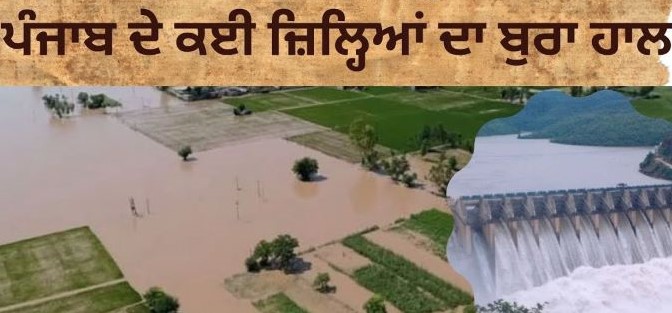

Every monsoon, Punjab braces for heavy rains, but this year’s floods have left behind devastation on an unprecedented scale. What was once fertile farmland is now covered with sand and silt, homes lie in ruins, and relief camps are brimming with families who have nowhere else to go. As the government speaks of compensation and relief, the real story lies in the villages, where victims are struggling to piece together their shattered lives.

Every monsoon, Punjab braces for heavy rains, but this year’s floods have left behind devastation on an unprecedented scale. What was once fertile farmland is now covered with sand and silt, homes lie in ruins, and relief camps are brimming with families who have nowhere else to go. As the government speaks of compensation and relief, the real story lies in the villages, where victims are struggling to piece together their shattered lives.

In Shahkot, farmer Baljeet Singh walks through what used to be his paddy fields. The land, once green and brimming with crop, is now a swampy wasteland. “I had invested nearly ₹3 lakh this season,” he says, staring blankly. “Not a single grain is left. Banks will ask for their money, but who will stand with us now?” For families like his, the floods were more than a natural disaster—they were an economic earthquake. Crops lost, cattle dead, and homes submerged mean that the very foundation of rural life has collapsed.Raj Rani, a widow from Ropar, tells her story with tears in her eyes. “Our mud house gave way in the rain. We took shelter in the gurdwara. It is not easy for women here. There is no privacy, no sanitation, and children are falling sick. They told us the government will compensate, but till today, we have seen nothing except promises.”

The receding waters have created a perfect breeding ground for disease. Doctors working in makeshift clinics report rising cases of gastroenteritis, fever, and dengue. “Clean drinking water is the most urgent need,” explains Dr. Harpreet Kaur, who is running mobile health units in Ferozepur. “People are drinking from the same stagnant pools where dead animals are floating. Unless sanitation improves, a health disaster is inevitable.”

Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann has assured the public that “no victim will be left behind.” The government has announced compensation for crop losses, free wheat seeds for the next sowing, and ₹7,200 per acre for farmers to clear silt from their land. Yet villagers complain of delays and bureaucracy. “They came, they took photos, and they left,” says Harbans Kaur from Ludhiana, whose house collapsed in the flood. “Not a single rupee has reached us. But they keep announcing on TV that help is on the way.” The Union Government has also pledged direct financial transfers to affected families, bypassing state bureaucracy. While this has been welcomed, critics argue that without local oversight, many families may still slip through the cracks.

In the absence of timely state action, civil society and diaspora groups have taken the lead. From gurdwaras running community kitchens to NRIs sending truckloads of relief supplies, ordinary citizens have become lifelines. Kulwinder Singh, an NRI volunteer, says, “We couldn’t sit abroad and watch Punjab drown. People here need food, blankets, and medicine immediately—not after months of paperwork.”

Floods in Punjab are not new, but experts argue that their intensity is worsening due to climate change and poor planning. Release of water from dams, encroachment on riverbeds, and neglect of embankments have turned heavy rains into disasters. Agricultural economist Dr. Sucha Singh Gill notes, “Punjab’s flood problem is man-made as much as natural. We need better coordination between states on dam releases, stronger embankments, and a long-term climate adaptation plan. Otherwise, this cycle will repeat every few years, and the victims will always be the same poor farmers.”

For now, families remain trapped between uncertainty and hope. Children sit idle in relief camps instead of classrooms, elders replay the trauma of water entering their homes, and farmers wonder how to till fields now buried under sand. The promises of rehabilitation are many, but the trust in governance is thin. As Balwinder Kaur, a 60-year-old from Patiala, sums it up: “Floods come and go, but it is always we poor people who pay the price. Governments change, but our suffering does not.”