As a Sikh from Punjab, the “Kaur to Khan” (K2K) ideology also called the “grooming” pierces my soul deeply. It’s not about generalising hate for Muslims; many are our neighbours, friends, and fellow humans living in peace. But this sinister plan, hidden under the guise of love, is a venomous threat that preys on our daughters, eroding their identity and faith.

As a Sikh from Punjab, the “Kaur to Khan” (K2K) ideology also called the “grooming” pierces my soul deeply. It’s not about generalising hate for Muslims; many are our neighbours, friends, and fellow humans living in peace. But this sinister plan, hidden under the guise of love, is a venomous threat that preys on our daughters, eroding their identity and faith.

Just this January 2026, a 15-year-old Sikh girl in West London was rescued after 200 community members protested outside her abductor’s home—a 30-year-old man arrested for grooming. Did any religiousleader from Punjab utter a single word on this? Their silence echoes louder than any sermon.

What breaks my heart even more is how our own community, led by religious gatekeepers obsessed with distancing us from Hindus, turns a blind eye to this sinister program. This confusion isn’t just political; it’s a betrayal of our Gurus’ legacy, leaving us vulnerable and divided. When will we wake up? When will the pain of our history force us to see clearly?

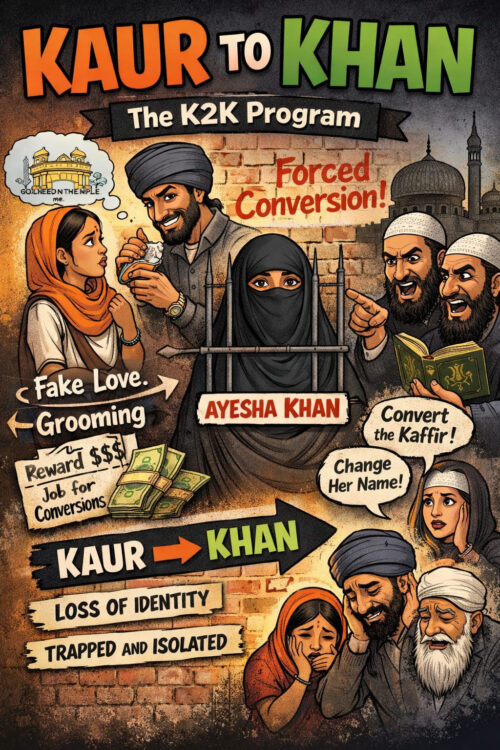

Imagine a young Sikh girl, full of dreams, lured into a trap. She meets someone who speaks her language, wears a kara, and whispers sweet promises. But it’s all a facade. The “Kaur to Khan” (K2K) ideology, exposed since the 1990s, targets our Kaurs—our princesses—for grooming and forced conversion to Islam. Perpetrators, often from Pakistani-origin gangs in the UK, rename them “Khan,” isolating them from family through drugs, threats, or emotional blackmail. Sikh Awareness Society reports document over 200 cases in the last five years alone, with

estimates of thousands affected over 50 years in cities like London, Birmingham and Bradford. A 1997 leaflet even urged Muslim men to see Sikh

women as “easy targets,” offering rewards like money or jobs for conversions.

This isn’t random crime, it’s rooted in a twisted ideology. Perpetrators recite Quran verses during abuse, force nikah marriages, and treat non-Muslims as “kaffirs” to be conquered. It echoes Pakistan’s horror, where human rights groups report 1,000 forced conversions of Hindu and Sikh girls yearly. Experts link it to Islamist views rewarding deception for “converting

infidels,” akin to India’s “love jihad.” Why us Sikhs? Our history of resistance makes us a trophy.

Our Gurus taught us unyielding resistance. Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji martyred himself for Hindu pandits’ rights against forced conversion by Mughals. But for his sacrifice, the entire demography of India would be different today. No Hindu, No Sikh. Only Muslims. The Sahibzadas, mere children of 7 and 9, refused to convert, or wear the Mughal skull cap a symbol of forced Islam and chose to be bricked alive in Sirhind. Their blood at Fatehgarh Sahib cries out against coercion. Partition in 1947 amplified that cry: Sikhs butchered, women raped, families torn as Muslim mobs ravaged Punjab. Trains of death, villages in flames—over a million perished, our wounds still raw. How can we forget?

.

But days later, a Muslim man strolled into the Golden Temple wearing a skull cap,rinsing his mouth in the sacred Sarovar, performing his rituals on video. Any such blasphemy from a Hindu or even a Sikh would have been, and has been dealt differently. Unfortunately, we have not been able to differentiate a “skull cap” from a cap to keep heads warm in winters.

This mess stems from a self-inflicted Hindu-phobia, a paranoia cultivated by leaders

to “differentiate” us. Panth khatre vich hai has is a perpetual slogan. Obsessed with imaginary threats from Hinduism, they ignore real dangers: K2K grooming abroad, massive Christian conversions at home through allure or aid. Sikhism is a timeless virtue—no one can steal it. But creating phobias doesn’t protect us; it blinds us. Our religio-political masters preach fear of Hinduism while staying completely deaf and dumb to K2K and Christian conversions. This selective blindness isn’t progress; it’s

vulnerability, making us shout at shadows while predators lurk.

Sikhism demands courage: expose coercion, protect our daughters, preserve consent. Silence empowers exploiters. Until we shed this paranoia and embrace Guru’s path of honest alliance and justice, the confusion will erode us into history books much sooner than expected. Guru Tegh Bahadur’s and the Sahibzadas’ sacrifices have taught us something to learn and practice in our lives.

Punjabi Language in Punjab: Numbers That Tell a Divided Story (India vs Pakistan)

By Satnam Singh Chahal

Introduction

Punjabi is one of the most spoken languages globally, yet its institutional position differs sharply across the two Punjabs—India and Pakistan. While the language thrives culturally on both sides, numerical data related to population, speakers, and education reveal a deep policy divide that continues to shape the future of Punjabi.

Population Comparison: A Numerical Contrast

Punjab in Pakistan has an estimated population of 127 million (2023), making it one of the most populous regions in South Asia. In contrast, Indian Punjab has about 30 million people (2011 Census). Despite having more than four times the population, Pakistani Punjab does not provide Punjabi with official or administrative status, whereas Indian Punjab does.

(If represented as a chart, Pakistan’s population bar would tower over India’s—yet official language recognition would appear inverted.)

Punjabi Speakers: Percentages vs Power

The percentage of Punjabi speakers presents an even more striking picture:

Pakistan Punjab: Around 67% of people speak Punjabi

Indian Punjab: Over 90% of people speak Punjabi

Numerically, Pakistan has far more Punjabi speakers in absolute terms, yet Punjabi remains absent from government offices, courts, and most schools. In India, despite fewer speakers in total numbers, Punjabi enjoys constitutional protection and official usage.

(A percentage chart would show India with a higher usage rate, but Pakistan with a much larger speaker base.)

Education System: Where Numbers Translate Into Policy

In Pakistan, the medium of instruction is primarily Urdu and English, with Punjabi rarely used in formal education. Punjabi, written in the Shahmukhi script, has minimal representation in textbooks and examinations. This has resulted in low literacy development in the mother tongue, despite widespread spoken use.

In contrast, Indian Punjab teaches Punjabi in schools using the Gurmukhi script, from primary to higher levels. Government data and ground reality show that children learn, read, and write Punjabi as part of mainstream education—turning percentages into long-term linguistic sustainability.

Administration and Governance: Measured Absence

In Indian Punjab, Punjabi is used in:

Government notifications

Legislative proceedings

Local administration

Cultural and academic institutions

In Pakistan, Punjabi’s presence in governance is almost 0%, despite being the most spoken language. Urdu and English dominate official domains, creating a mismatch between spoken reality and administrative practice.

Cultural Strength vs Institutional Numbers

Culturally, Punjabi music, poetry, and folklore remain strong in both regions. However, culture alone cannot compensate for institutional neglect. Where India’s policies reinforce Punjabi through education and administration, Pakistan’s numbers show a language strong at home but weak in public systems.

Conclusion

The numbers are clear and revealing. Pakistan has more Punjabi speakers, but less Punjabi power. India has fewer speakers, but greater institutional support. This comparison proves that the survival of a language depends not only on how many people speak it, but on how seriously the state supports it. Without policy reform and educational inclusion, Punjabi in Pakistan risks remaining a spoken language without a formal future