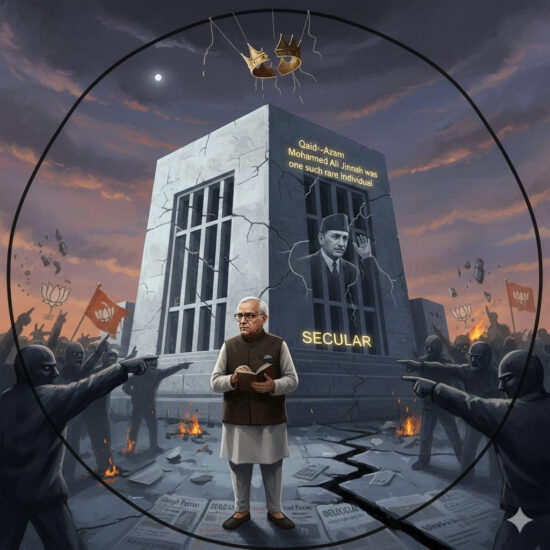

If Morarji Desai’s Nishan-e-Pakistan became a permanent question mark over his national security legacy, L.K. Advani’s virtual tryst with Qaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah at the Karachi mausoleum in June 2005 proved far more final—an ultimate political epitaph, as it were, carved into marble over his prime ministerial ambitions. Unlike Desai, Advani received no Pakistani decoration. Yet the political damage was deeper, precisely because it was self-inflicted: not an honour bestowed in Islamabad, but a handful of sentences written in the visitors’ book and spoken soon after at the Mazar-e-Quaid. For a leader long regarded as the chief architect of the Hindutva revival and the Ram Mandir movement, those words were instantly read within the Sangh Parivar as ideological apostasy. And once that line was crossed, the Karachi comments became the “Pakistan trap” from which Advani never quite emerged.

If Morarji Desai’s Nishan-e-Pakistan became a permanent question mark over his national security legacy, L.K. Advani’s virtual tryst with Qaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah at the Karachi mausoleum in June 2005 proved far more final—an ultimate political epitaph, as it were, carved into marble over his prime ministerial ambitions. Unlike Desai, Advani received no Pakistani decoration. Yet the political damage was deeper, precisely because it was self-inflicted: not an honour bestowed in Islamabad, but a handful of sentences written in the visitors’ book and spoken soon after at the Mazar-e-Quaid. For a leader long regarded as the chief architect of the Hindutva revival and the Ram Mandir movement, those words were instantly read within the Sangh Parivar as ideological apostasy. And once that line was crossed, the Karachi comments became the “Pakistan trap” from which Advani never quite emerged.

The Karachi Homecoming: A Sentimental Journey Turns Political Blunder

Lal Krishna Advani was born on 8 November 1927 in Karachi, Sindh, then part of the Bombay Presidency in British India. A Sindhi Hindu from a Lohana family, he grew up in pre-Partition Sindh, studied at St. Patrick’s High School in Karachi, and migrated to India with his family after the cataclysm of 1947.

For Advani, returning to Karachi in June 2005 was a deeply personal journey to his birthplace and childhood home. But as National President of the Bharatiya Janata Party and Leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha, sentimentality came with enormous political risk. That risk materialised the moment he stepped into the Mazar-e-Quaid, the mausoleum of Pakistan’s founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah—where a visitor’s book can sometimes double as a political ledger.

On 4 June 2005, Advani visited Jinnah’s mausoleum in Karachi and signed the visitors’ book. His tribute read: “There are many people who leave an inerasable stamp on history. There are very few who actually create history. Qaid-e-Azam Mohammed Ali Jinnah was one such rare individual.” The next day, 5 June 2005, speaking at an event organised by the Karachi Council on Foreign Relations, Economic Affairs and Law, Advani praised Jinnah’s 11 August 1947 speech to Pakistan’s Constituent Assembly as “a classic exposition of a secular state” and described Jinnah as an “apostle of Hindu-Muslim unity” who upheld minority rights.

In Pakistan, Advani’s remarks were received as a remarkable gesture of statesmanship from a man long portrayed as a hardline Hindutva leader and architect of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement. In India, however, they detonated like a political landmine at the heart of the Sangh Parivar—and the Karachi visit began to look less like a homecoming and more like a trapdoor.

The Offices He Held: President of BJP and Leader of Opposition

Advani’s Pakistan visit did not occur on the margins of his career. It came at his peak as the tallest leader of the BJP following the withdrawal of Atal Bihari Vajpayee from active politics after the 2004 electoral defeat.

At the time of his Karachi remarks, Advani held two crucial positions:

National President of the BJP (his third term as party president, 2004–2005).

Leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha (2004–2009), heading the principal opposition to the UPA government led by Manmohan Singh.

Effectively, Advani was the BJP’s presumptive prime ministerial candidate for the next general election. The Karachi trip was widely interpreted as an attempt to soften his image, to transition from “Hindutva hardliner” to “statesman,” and to reclaim centrist ground after the shock defeat of 2004.

The Sangh Parivar’s Fury: Ideological Apostasy

The reaction from the RSS and the broader Sangh Parivar was immediate and severe. The BJP had built its political narrative around viewing Jinnah as the chief architect of Partition, the creator of an explicitly Muslim homeland that stood in opposition to the idea of Akhand Bharat. For the BJP president himself to describe Jinnah as secular and an apostle of Hindu-Muslim unity was, in their eyes, an assault on the party’s foundational story. In this ideological universe, the mausoleum was not a monument—it was a minefield.

RSS leaders expressed “deep anguish” and “dismay” over Advani’s comments. Hardline affiliates like the Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Bajrang Dal launched sharp public attacks. BJP cadres, particularly in Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh, were bewildered and angry. Within days, a chorus grew that the party could not have a president who praised Jinnah.

On 7 June 2005, facing intense internal pressure, Advani submitted his resignation as BJP president. This plunged the party into a leadership crisis. While some senior leaders, including Atal Bihari Vajpayee, privately sympathised with Advani’s broader attempt to reinterpret Jinnah’s legacy in the light of his 11 August speech, the RSS leadership made it clear that the ideological line had been crossed.

After intense damage control, Advani’s resignation was not immediately accepted, and he briefly continued as president. However, the equilibrium was irreparably disturbed. The RSS had sent a message: on Jinnah, there would be no deviation—not even from the party’s tallest ideologue.

By December 2005, at the BJP’s silver jubilee celebrations in Mumbai, Advani stepped down as party president, and Rajnath Singh took over. The Jinnah episode had formally ended his tenure at the apex of the party organisation.

The Long Shadow: How Karachi Killed the Prime Minister-in-Waiting

Although Advani remained Leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha until 2009 and was later projected as the BJP’s prime ministerial candidate for the 2009 general elections, the Karachi controversy cast a long, dark shadow over his ambitions. In practice, the inscription and the speech became the shorthand for an alleged ideological lapse—an epitaph others insisted on reading aloud, again and again.

The Jinnah remarks inflicted three kinds of damage on Advani’s political standing:

Loss of RSS Trust: The RSS never fully restored its earlier confidence in Advani. For a leader whose rise had been inseparable from Sangh support—from the Ram Rath Yatra to the Babri movement—this erosion of trust was fatal. Without RSS enthusiasm on the ground, Advani’s 2009 prime ministerial bid lacked organisational energy.

Confusion in the Cadre: For decades, BJP workers had internalised the narrative of Jinnah as the villain of Partition. When the party’s own “Iron Man” declared Jinnah’s vision secular, it created cognitive dissonance and ideological confusion among the cadre. Many felt betrayed; others were simply bewildered. This weakened Advani’s moral authority within the party.

Perception of Opportunism: Opponents and sceptics within the BJP portrayed the Karachi remarks as opportunistic rebranding—an attempt by a hardened Hindutva leader to suddenly don the robes of a moderate in pursuit of acceptability among centrist voters. This perception cemented resistance within the party to handing him the reins of government.

The outcome was evident in the 2009 Lok Sabha elections. Despite being formally declared the BJP’s prime ministerial candidate, Advani could not prevent the Congress-led UPA from securing a comfortable victory. Manmohan Singh returned as Prime Minister, and Advani’s moment passed.

After 2009, Advani’s stature gradually receded. He ceded the role of Leader of the Opposition to Sushma Swaraj and found himself increasingly sidelined as a new generation, culminating in Narendra Modi’s rise, took control of the party. By 2014, Advani was no longer central to the BJP’s narrative. In 2019, he retired from electoral politics, having never achieved the office he had spent a lifetime approaching.

No Regrets: Advani’s Defence of His Jinnah Remarks

Unlike many politicians who retreat from controversial statements, Advani never truly recanted his Karachi remarks. In his 2008 autobiography My Country, My Life, he wrote that he had “no regrets” about what he said on Jinnah, though he expressed hurt at the intensity of the backlash.

In interviews, he reiterated that he had merely cited Jinnah’s 11 August 1947 speech, in which Jinnah spoke of religious freedom and equality of citizens, as an articulation of a secular state. Advani argued that acknowledging this did not mean endorsing Partition, nor did it whitewash the tragedies of 1947. He felt misunderstood by his own ideological family.

Yet, in the unforgiving world of Indian electoral politics, and particularly within the BJP–RSS universe, nuance around Jinnah remains unacceptable. The ideological narrative demands a clear villain, and any attempt at reinterpretation is treated as heresy.

The Jaswant Singh Echo: How Jinnah Continues to Claim Careers

Advani’s Karachi episode was not an isolated case. In August 2009, BJP leader and former External Affairs Minister Major (Retd) Jaswant Singh published Jinnah: India, Partition, Independence, arguing that Jinnah had been unfairly “demonised” in India and that Nehru’s centralised vision contributed significantly to Partition. The backlash was swift: within two days of the book’s release, the BJP expelled Jaswant Singh from the party, and the Gujarat government banned the book—a ban later struck down by the High Court.

In both cases—Advani in 2005 and Jaswant Singh in 2009—the trigger was not a Pakistani award but an Indian leader offering a more complex, less demonised reading of Mohammad Ali Jinnah. The punishment was swift and severe. In the BJP’s ideological universe, to soften Jinnah’s image is to destabilise a central pillar of its foundational story about Partition and nationhood.

Honours, Gestures and the Hindu Nationalist Double Bind

The careers of Desai, Advani and Jaswant Singh reveal a peculiar double bind for Indian leaders in relation to Pakistan:

If a leader accepts honours from Pakistan (Desai), he may later be portrayed as compromised or even treacherous, especially if his policy record can be linked to strategic setbacks like Pakistan’s nuclearisation.

If a leader praises Pakistan’s founder (Advani, Jaswant), even in a narrowly textual or historical way, he may be punished for ideological betrayal, regardless of his decades of service to the Hindu nationalist cause.

In both cases, Pakistan becomes the trap: either through an external honour that becomes an internal accusation, or through internal speech that is framed as external validation of the “enemy’s” narrative.

From Karachi to Delhi: A Life’s Arc Rewritten by a Few Words

The irony of L.K. Advani’s career is almost Shakespearean. Here was a man who more than any other single leader built the BJP’s mass base; who turned a two-seat party in 1984 into a national challenger; who served as Home Minister and Deputy Prime Minister; and who was widely acknowledged as the architect of the party’s ideological consolidation.

Yet his prime ministerial dream died not in an election, not in a scandal of corruption or governance, but at the marble mausoleum of the man his own party had cast as India’s historic antagonist. A few sentences in a visitor’s book in Karachi and a speech quoting Jinnah’s Constituent Assembly address were enough to recast Advani—from “Iron Man” of the BJP to a leader the RSS considered ideologically unreliable.

In that sense, Advani’s story completes the arc begun in Morarji Desai’s. Where Desai’s Pakistani honour became a prism to question his actions on Kahuta and RAW, Advani’s Pakistani gesture—his praise of Jinnah—became the lens through which his four-decade-long ideological journey was reassessed and, in the eyes of many in the Sangh, found wanting.

The Pakistan Chakravyuh

For Indian leaders, Pakistan is not merely a neighbouring state; it is a political chakravyuh—a tight, circular formation of narratives from which escape is difficult once one steps in. A peace gesture can be branded appeasement, an award recast as compromise, and a scholarly or textual reassessment condemned as betrayal. The Desai and Advani episodes show that in India’s contemporary political culture, anything that can be interpreted as softening towards Pakistan—or towards its founding figure—can become a career-defining entrapment.

Morarji Desai entered this chakravyuh through the Nishan-e-Pakistan, conferred against the enduring allegations that he weakened RAW and, by strategic indiscretion, helped Pakistan’s nuclear programme endure. L.K. Advani entered it not through a medal, but through words—an inscription in Karachi and a speech referencing Jinnah—that cost him the one office he had spent a lifetime approaching but never attained.

Between Desai’s decoration and Advani’s mausoleum lies a stark lesson in Indian politics: on Pakistan, intent rarely survives; perception almost always does. Whether one acts out of Gandhian idealism, strategic naïveté, or a bid for statesmanship, the system judges not by context or nuance but by a single blunt question—“Which side are you on?”

For Indian nationals in public life, gestures linked to Pakistan do not merely adorn a biography or burnish a legacy. They can become the wood and nails of a public crucifixion—or, just as often, the Pakistan chakravyuh itself: a moment that closes in from all sides, leaving a career to be remembered not for decades of labour, but for a few words that were meant to rise above history.

Postscript: How Vajpayee Escaped the “Pakistan Trap”

If anyone in the BJP should have been ensnared by the same Pakistan-centred blowback that crippled Advani, it was Atal Bihari Vajpayee—because he tested the peace track more boldly, more publicly, and earlier. He rode the Delhi–Lahore bus on 19 February 1999, putting his personal authority behind a thaw and signalling that a statesman’s reach could exceed a party’s reflexes.

What followed was the cruelest possible reversal. Within months came the Kargil ingression—an infiltration across the Line of Control into high-altitude positions that gave Pakistan’s forces an initial, illicit advantage on the commanding heights. India paid a heavy price to dislodge them and regain those peaks—an effort measured not merely in operational difficulty but in lives lost in some of the most punishing terrain and conditions in modern warfare. When the fighting ended on 26 July 1999, the political story that emerged was “victory”—Kargil Vijay Diwas. It was astute repackaging, because in a strict territorial sense India did not capture new ground; it reclaimed territory and positions it had held before the infiltration. Yet the reclamation itself, given the cost and complexity, was worthy of national pride—and Vajpayee understood that the country needed a language of honour, not a vocabulary of technicalities.

In a sense, Kargil also rescued Vajpayee from the charge of naïveté that Lahore might otherwise have attracted. A peace initiative betrayed so starkly can either destroy a leader or sanctify him, depending on how the subsequent national response is framed. Vajpayee’s posture—firm in conflict, dignified in intent—allowed him to keep the moral high ground while the armed forces earned the operational one.

His next brush with the same peril came with the Agra Summit in July 2001. It collapsed without a joint declaration, and that failure—ironically—helped protect him domestically. Had the summit produced an agreement visibly shaped by concessions, it might have become a noose in the ideological arena, especially in a party ecosystem where “softness” towards Pakistan can be weaponised as betrayal. But history unfolded differently: Agra failed, and therefore no “sell-out” narrative could attach itself to Vajpayee in the way it attached itself to others for far less.

That is the core reason Vajpayee survived the Pakistan machinations that damaged so many careers. Lahore established intent; Kargil demonstrated resolve; Agra avoided the optics of concession. He carried the burdens of outreach, betrayal, and war—yet remained a BJP icon even after the unexpected loss in the 2004 general elections. He retained that stature until his death on 16 August 2018, a rare case of a leader whose Pakistan gambits did not become a crucifixion, but instead were absorbed into a legacy of measured statesmanship and national fortitude.