Babu Mann’s lyric endures because it captures a collective truth: in Punjab, power has long been expected to announce itself loudly not just to function, but to dominate. Red beacons may have vanished from official vehicles, but it bears remembering that they disappeared only after directions of the Supreme Court, followed by a Central notification in 2017. Political virtue did not end VIP culture; judicial compulsion did. The symbol was removed, but the psychology that demanded it was left untouched.

Babu Mann’s lyric endures because it captures a collective truth: in Punjab, power has long been expected to announce itself loudly not just to function, but to dominate. Red beacons may have vanished from official vehicles, but it bears remembering that they disappeared only after directions of the Supreme Court, followed by a Central notification in 2017. Political virtue did not end VIP culture; judicial compulsion did. The symbol was removed, but the psychology that demanded it was left untouched.

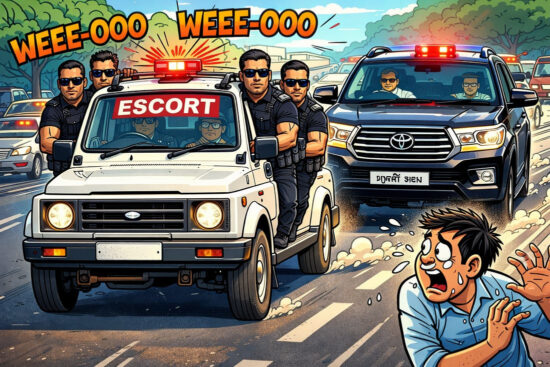

What we see today — private pilot vehicles, pseudo-PSOs, bouncers in police-like uniforms, traffic bullied aside by sirens and stares — is not a regression. It is an adaptation. VIP culture has not died; it has gone underground and privatised itself.

It must be acknowledged upfront that the Punjab Police’s recent decision to act firmly against this menace is a welcome and necessary step. Impersonation of authority, illegal escorts and intimidation on public roads strike at the idea of citizenship itself. Enforcement restores some balance. But enforcement alone cannot cure a psychological habit.

Because this is not merely about security.

It is about why power in Punjab feels the need to be seen, heard and feared.

The Psychology of Throwing Weight Around

At its core, this behaviour reflects status anxiety. Leaders and elites who are secure in institutional legitimacy rarely need to display force theatrically. Those who are unsure of their authority : intellectually, educationally, politically, socially or morally tend to compensate through spectacle. Convoys, uniforms and muscle become emotional crutches.

There is also a deeply internalised association between power and intimidation. In much of North India, authority has historically been enforced rather than consented to — by colonial rulers, tribal mindset, feudal landlords and coercive policing. Over time, domination became normalised as leadership. The ruler who did not frighten was seen as weak.

This psychology produces a dangerous confusion: respect is mistaken for fear.

But there is a second, more uncomfortable truth — leaders do this because society rewards it.

The Public Is Not Innocent

Yes, elites throw their weight around. But they do so knowing there is an audience. A politician or businessman with a convoy is not only intimidating traffic; he is also performing power for onlookers — for supporters who feel validated by proximity, for rivals who feel diminished, and for a public that has been trained to equate noise with importance.

In many ways, VIP culture is a co-production. The leader supplies the spectacle; society supplies the awe.

This is why such behaviour is rare in South India. There, mass movements, linguistic pride and social reform produced a different psychology: leaders derive legitimacy from institutions and delivery, not road dominance. Power does not need to shout to be recognised.

In Punjab and Haryana, by contrast, authority has remained performative. The louder the siren, the greater the assumed importance.

Political Promises vs Psychological Reality

This makes repeated political promises to end VIP culture especially hollow.

I was part of the Congress manifesto drafting committee for the 2017 Punjab elections, along with Mrs Rajinder Kaur Bhattal and Manpreet Singh Badal. Ending VIP culture was explicitly promised, because the public anger was genuine.

In 2022, the Aam Aadmi Party went further. Its Punjab manifesto stated clearly:

“No AAP MLA, minister, MP or any other senior leader will use vehicle with hooters and red beacon lights. VIP culture will be ended by cutting down personal security by 95%.”

This was not rhetorical flourish; it was a direct assault on entitlement.

Post-poll actions followed, including withdrawal of security. But what the manifesto underestimated was this: you can remove state security, but you cannot remove a mindset that equates power with intimidation. That mindset will simply rent muscle from the market.

Why Law Alone Will Not Fix This

This is why the current phenomenon is actually more dangerous. When intimidation is exercised through private actors rather than the state, accountability collapses. The abuse becomes informal, deniable and harder to regulate.

If VIP culture is to end, Punjab must confront the psychological roots:

• Leadership must decouple authority from spectacle

• Society must stop applauding intimidation as strength

• Media must stop amplifying convoys as status symbols

• Police must consistently crush impersonation and private theatrics

VIP culture survives because fear feels efficient and spectacle feels powerful. But in the long run, it corrodes institutions, humiliates citizens and cheapens authority itself. Punjab has banned red beacons by court order. Police have finally begun to act. Manifestos have said the right things.

The main battle is psychological ! and that is the hardest one of all.