Author’s Note: When public charitable trusts govern assets that shape the country’s corporate landscape, their rules cannot be rewritten by internal fiat. They must be examined in open court and under the Charity Commissioner’s independent and quasi-judicial gaze.

Author’s Note: When public charitable trusts govern assets that shape the country’s corporate landscape, their rules cannot be rewritten by internal fiat. They must be examined in open court and under the Charity Commissioner’s independent and quasi-judicial gaze.

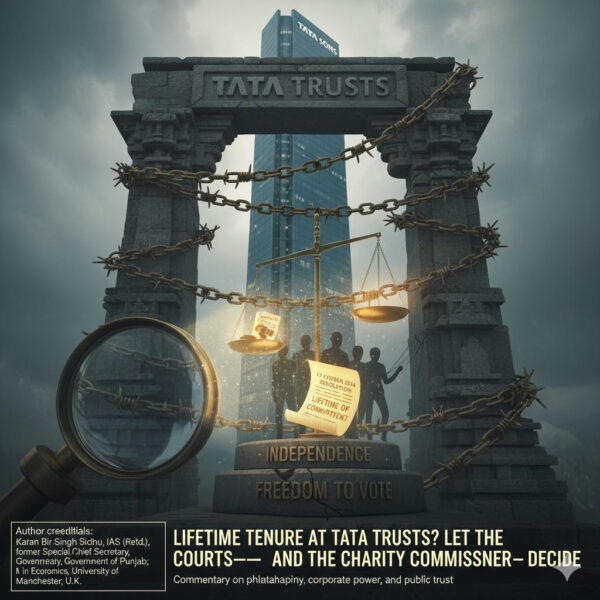

Lifetime Tenure at Tata Trusts? Let the Courts—and the Charity Commissioner—Decide

On 17 October 2024, the trustees of Tata Trusts had adopted a controversial resolution: upon renewal, trustees would enjoy lifetime tenure; any trustee who opposed a fellow trustee’s reappointment would be deemed “in breach of commitment” and unfit to serve. That single act has since become the legal flashpoint for a wider struggle over the governance of India’s most influential philanthropic network and, by extension, the stewardship of a sprawling business empire.

This is not merely an internal housekeeping matter. Tata Trusts are public charitable trusts. Their powers flow from public law; their privileges are bounded by fiduciary duty to beneficiaries who are, in effect, the public. For that reason alone, the legality and propriety of the 17 October resolution must be tested in a court of law and scrutinised rigrously by the office of the Charity Commissioner. Lifetime tenure by default—and punishment for dissent—clashes with first principles of charity governance: independence, accountability, and the freedom to vote one’s conscience in the public interest.

Public duty over private preference

India’s trust law and the regulatory architecture around public charities exist to ensure that control is exercised for the benefit of the public, not a particular faction, family, or cohort of insiders. A rule that entrenches trustees for life at the moment of “renewal,” while chilling dissent by threatening the dissenters’ own fitness, risks converting a public fiduciary into a private club. Even where a statute or ordinance permits limited categories of perpetual trustees, those carve-outs are exceptions, not a licence to negate rotation, renewal standards, or reasoned opposition.

The Charity Commissioner’s remit is precisely to prevent such drift. Judicial oversight must establish whether this resolution is ultra vires the Trusts’ deeds, contrary to public policy, or otherwise inconsistent with the statutory framework for public charities. If it passes muster, so be it—but the test must be transparent and legal, not political or personal.

Don’t conflate Tata Trusts’ governance with Tata Sons’ listing

A parallel debate has been allowed to muddy the waters: the question of whether Tata Sons should list. That issue is separate. Listing, deregistration, or any restructuring of a systemically important holding company must be resolved strictly under the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) framework and—where applicable—the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) guidelines. No resolution of the majority stakeholder, even a venerable public trust, can create a bespoke exemption from securities law or prudential norms. If exemptions are to be granted, they must be granted by the regulator, on articulated criteria of public interest and market integrity—not by private resolve.

Insisting on that separation is not hostility to the Trusts; it is fidelity to the rule of law. Markets depend on clarity. So do charities.

The new stewards: credentials under the public gaze

If lifetime tenure is the most contentious procedural stroke of 2024, the most consequential substantive move has been the recent reshaping of the Trusts’ boards. Given the outsized societal footprint of Tata Trusts, it is fair—indeed necessary—to examine the curriculum vitae of every newly inducted trustee.

Neville N. Tata brings next-generation continuity. Educated at Bayes Business School and INSEAD, he has cut his teeth inside the group’s consumer businesses—first in packaged foods and beverages, then scaling Zudio’s value-fashion format, and more recently heading the Star Bazaar hypermarket division at Trent. He already serves as a trustee on allied Tata charitable entities. Supporters will see in him a strategically literate operator with frontline retail experience; critics will worry about dynastic consolidation. Both views only heighten the need for robust guardrails: independence standards, conflict-of-interest disclosures, and performance-linked renewal rather than automatic perpetuity.

Bhaskar Bhat supplies institutional ballast. An IIT–IIM alumnus, he spent decades building Titan from a watchmaker into a diversified lifestyle powerhouse across jewellery, eyewear, and accessories. His reputation is that of a systems-builder who marries brand to distribution with discipline. In a philanthropy that increasingly funds complex, multi-year programmes—from public health to skilling—a trustee who understands scale, metrics, and governance is an asset. Yet precisely because of his deep Tata lineage, the board must show, through process not personality, that dissent is protected and diversity of view is prized.

A word, too, on Venu Srinivasan, the industrialist long associated with manufacturing excellence and Total Quality Management. His elevation, and the subsequent modification of tenure to align with evolving public-trust norms, illustrates the point of regulatory oversight: even eminent trustees must fit within the law’s outer frame.

Who is out—and why it matters

Equally instructive are the departures and non-renewals. Mehli Mistry—long seen as a counterweight within the Trusts’ ecosystem—has exited amid dispute over reappointment, and is contesting the legal effect of the 17 October 2024 resolution. Vijay Singh, a seasoned public administrator, stepped down from the Tata Sons board earlier but remains a trustee, underscoring the intricate overlap between Trust governance and group representation. These moves are not banal personnel shifts; they rebalance power. In a public charitable trust, such rebalancing must be justified by transparent criteria, not by a chilling rule against recorded dissent.

What should happen next

Three steps would restore confidence:

Judicial and regulatory testing of the 17 October resolution. The courts—and the Charity Commissioner—should determine whether lifetime tenure “upon renewal” and sanctions for dissent comply with trust deeds, statute, and public policy. If they do not, they should be struck down or read down.

Hard separation of issues. Decisions about Tata Sons’ listing or regulatory status must be taken within SEBI and RBI rulebooks, on the record, and with full reasoning. Trust resolutions cannot be used as a proxy mandate to bend market rules.

Modern governance inside the Trusts. Publish a clear appointments matrix (skills, independence, term limits), adopt regular third-party evaluations, and guarantee that opposing votes are not only permitted but minuted and respected. Public charities should be exemplars of transparency, not exceptions to it.

Tata Trusts have, for over a century, underwritten institutions and ideas that make India stronger. Precisely because of that legacy, their governance must be beyond reproach. Lifetime tenure by default, and penalties for dissent, are the wrong signal. Let the matter be tested where it belongs—in court and before the Charity Commissioner—so that the Trusts’ next century is anchored not merely in continuity, but in credibility.