On 9 September, the Prime Minister surveyed flood-hit districts in Punjab and announced a special grant-in-aid of ₹16,000 crore—described as “over and above” the roughly ₹16,000 crore already credited to the State exchequer under disaster-management heads. Within hours, Punjab widened the frame: while immediate relief was welcome, its larger claim—approximately ₹50,000 crore in unpaid GST compensation—was flagged as the real test of fiscal federalism. The juxtaposition was deliberate. Disasters strain today’s cash balance; the GST compact speaks to tomorrow’s predictability. Punjab argues that the two are bound by trust and must be resolved in tandem.

On 9 September, the Prime Minister surveyed flood-hit districts in Punjab and announced a special grant-in-aid of ₹16,000 crore—described as “over and above” the roughly ₹16,000 crore already credited to the State exchequer under disaster-management heads. Within hours, Punjab widened the frame: while immediate relief was welcome, its larger claim—approximately ₹50,000 crore in unpaid GST compensation—was flagged as the real test of fiscal federalism. The juxtaposition was deliberate. Disasters strain today’s cash balance; the GST compact speaks to tomorrow’s predictability. Punjab argues that the two are bound by trust and must be resolved in tandem.

Relief and Compensation are Not the Same Cheque

Emergency relief and GST compensation belong to different policy universes. Relief is about speed: cash on the ground, materials in warehouses, culverts rebuilt before the next rain. Compensation is about credibility: was the Union–State fiscal bargain of 2017, meant to protect state treasuries, honoured in both letter and spirit? When the Central Government says, “We’ve topped up your relief over and above SDRF/NDRF balances,” it may still be true for a state to argue that the structural revenue gap created by the shift to GST remains unaddressed. Punjab’s position is straightforward: honour both—the immediate obligation to households and the longer obligation to a State that reorganised its tax system in good faith, alongside other members of the Union.

Is Punjab’s Demand Unique?

Not really. Several states—particularly those led by Opposition coalitions—have voiced similar concerns: that the GST transition has left a persistent, state-specific gap which the clean sunset in June 2022 did not resolve. Southern manufacturing hubs and eastern commodity producers highlight destination-based asymmetries; services-heavy states fear shocks from recent rate rationalisation; and agrarian states with large pre-GST purchase-tax bases (Punjab among them) argue that the design under-captures value in their supply chains. The figures each state cites may differ, but the refrain is common: if citizens continue to pay a sin-goods levy and GST 2.0 contemplates major structural changes, then a time-bound backstop for structurally short states should be squarely on the negotiating agenda.

The 2017 National Consensus: A Promise With a Sunset Clause

Under the GST (Compensation to States) framework, the Union guaranteed every state a 14% compound annual growth on a 2015–16 base of subsumed taxes for five years. Any shortfall was to be covered through a dedicated Compensation Cess on sin and luxury goods. Two features were central. First, the 14% growth guarantee was deliberately generous to secure consensus. Second, the assurance was time-bound, designed to taper once GST’s compliance and buoyancy gains took hold. The law’s sunset came in June 2022 for most states.

Where the Architecture Buckled: COVID and “Back-to-Back” Borrowings

COVID-19 decimated cess inflows as the national—and indeed the global—economy ground to a halt, just as the guaranteed revenue path kept rising. The Centre’s fix was a “back-to-back” borrowing window: it borrowed centrally in 2020–21 and 2021–22 and passed the funds on to states, keeping those amounts outside their normal debt limits. To service these borrowings, the Compensation Cess was extended until March 2026—explicitly to retire this debt, not to prolong the guarantee. Liquidity was bridged, but a grievance lingered: citizens continued to pay the hefty compensation cess, while states facing persistent shortfalls saw those very inflows pre-committed to debt repayment, not to compensation flowing into their treasuries.

Karan Bir Singh Sidhu, IAS (Retd.), former Special Chief Secretary, Punjab, writes on the intersection of constitutional probity, due process, and democratic supremacy.

Two Stories, One Ledger

The Centre’s reading: The legal chapter regarding GST compensation to the states is closed. Compensation admissible under the five-year window has been paid in to to; subsequent cess collections are rightly reserved for COVID-era debt service of the loan raised by the central government. Any fresh demand must be a new and comprehensive policy decision, not an unpaid bill under an old law.

Punjab’s reading: The structural gap did not vanish on a date of June 2022 in the calendar. Punjab’s pre-GST tax basket—especially purchase-tax dynamics in agri-trade—does not map cleanly onto a destination-based GST. The State pegs its cumulative gap around ₹49,727 crore and calls it “pending,” not as a mere rhetorical flourish but as a claim to the spirit of the bargain.

Why Punjab’s Structure Matters

GST, being destination-based, rewards diversified consumption and services ecosystems. Punjab’s profile is narrower. Its pre-GST purchase-tax regime captured value at points in the agricultural chain that GST’s design does not equally catch. Add leakages in sin-goods (which erode both state excise and the very cess that funds compensation), and a structural shortfall is unsurprising. In plain terms: even with better compliance, Punjab’s “natural” GST buoyancy may sit below the 14% protected path that underwrote the transition.

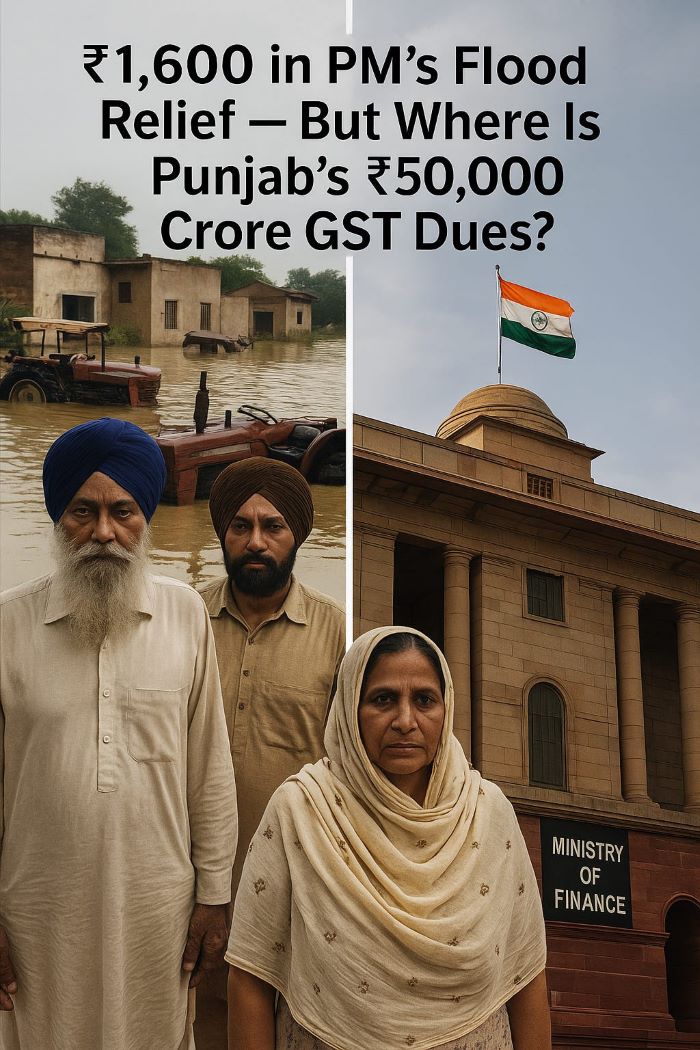

The “Over and Above” Moment—and the Optics of Magnitudes

Announcing ₹1600 crore for floods “over and above” existing disaster funds was meant to signal the Prime Minister’s generosity—accompanied by a gentle reminder of fiscal discipline expected from Punjab. Yet it inevitably invited comparison with the much larger GST compensation figure of nearly ₹50,000 crore. For households knee-deep in water, the distinction is academic, if not meaningless; for policymakers, it is the crux. Relief must be fast and front-loaded. Compensation must be predictable and rules-based. Conflating the two is unhelpful; sequencing them is essential.

What Is Punjab Actually Asking For?

Behind the political pitch sit three concrete asks:

Recognition of a verified structural gap. Not arrears under a lapsed law, but an enduring mismatch between design and reality, of the national GST consensus and framework.

A post-2026 mechanism. If the cess sunsets after debt service, what replaces the cushion for a handful of structurally short states?

A negotiated settlement. A quantified, time-bound transfer that closes the cumulative gap and then tapers.

Due in Law vs Due in Good Faith

In strict statutory terms, the Centre can plausibly say “nothing is due.” In equity—and, arguably, in economic common sense—Punjab can say “the job is unfinished.” Both positions can be right within their own frames. That is why the debate must move from abstractions to arithmetic. In our view, it should be one of the first and foremost tasks of the current Central Finance Commission to resolve this issue—if necessary, by issuing an interim award without delay.

A credible reconciliation should:

Lock the base-year series and the protected path;

Reconcile actuals, stripping out one-offs and litigation-stayed amounts;

Attribute rate and exemption changes with state-wise incidence;

Separate dues to June 2022 from post-June 2022 structural gaps.

Publish it with signatures from both sides. When citizens are paying a cess, they deserve a transparent ledger.

A Realistic Timeline: When Might We See Movement?

There are three natural decision windows. First, the next substantive GST Council sitting on cess rate rationalisation, in the context of states’ demands for compensation beyond June 2022—where a balanced package could pair a narrow structural-gap instrument with compliance gains. Second, the Union Budget cycle—where a transitional grant line could be created without amending the core GST law. Third, the post-March 2026 horizon—when debt-service obligations ease and the fate of the cess (or any successor levy) can be recast. None of these require the theatrics of brinkmanship; all of them require a coalition and a spreadsheet. The Central Finance Commission can also be mandated to take up the whole, or at least part, of this task—provided its scope is clearly delineated.

Reframe the claim. Move from “arrears” to a time-bound structural-gap settlement. Propose a three-year glide path—front-loaded for liquidity, tapering thereafter—backed by a jointly certified reconciliation.

Make it a package. Table a Purchase-Tax Equalisation Grant for agrarian states, computed off audited pre-GST series and designed to sunset. Pair it with a 90-day anti-evasion sprint against sin-goods leakages and carousel fraud, using e-way bill analytics, e-invoicing trails, and freight data.

Widen the base. Present a services-expansion plan (ITeS, health care, logistics, higher education) and an agro-processing push to deepen destination consumption within the State.

Build allies. Convene a coalition of similarly situated states; a GST Council solution favours groups with data, not solo speeches.

For the Centre

Offer a tapered, conditional bridge. A transitional grant focused on states with verified structural gaps, tied to measurable compliance gains and with a hard sunset.

Keep the cess honest. Once COVID borrowings are extinguished, commit to a public review of the cess’s future—whether sunset, shrink, or a narrow successor instrument with strict eligibility.

Tweak at the margins. Consider temporary IGST apportionment refinements or settlement-cycle adjustments that improve cash-flows for identified states without rewriting first principles.

National anti-evasion compact. Scale joint audits and data-sharing so that growth in the GST base pays for any transitional support.

For the GST Council

Mandate sunlight. Commission a joint audit and publish a state-wise dashboard tracking the protected path, actuals, and gaps.

Pair carrot and stick. Link any structural-gap support to a Council-wide anti-evasion plan and measured pruning of exemptions—so the medium-term effect is fiscally neutral.

Set dates, not vibes. Lock a calendar for rate rationalisation, reconciliation publication, and a post-2026 cess decision.

The Principle at Stake

Floods test the State’s capacity to act today. Fiscal federalism tests its capacity to keep faith across years. Punjab’s case will be strongest if it seeks not perpetual alimony, but transition support with a defined sunset and reforms with teeth. The Centre’s case will be strongest if it moves beyond “the law is closed” to “the ledger is clear, the bridge is narrow, and the sunset is real.” Citizens have paid the cess; they deserve both swift relief and an honest reckoning. The surest way to deliver that is a modest, measurable settlement now, a bigger GST base tomorrow, and a clean sunset the day after.

For the flood-hit villages, the politics and optics are almost incomprehensible. The Prime Minister’s visit showed empathy; immediate relief is the need of the hour, while the weightier issues we have discussed can and should proceed through a time-bound process.