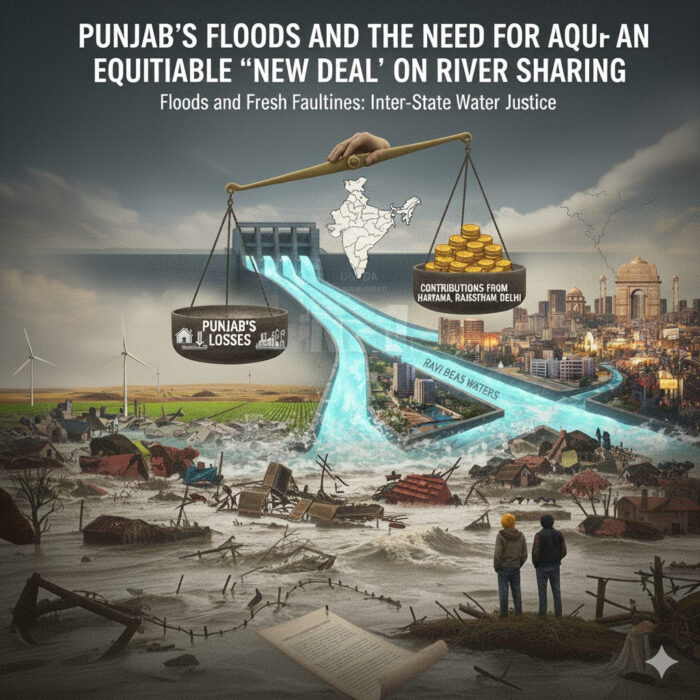

In the wake of the devastating floods of 2023 and 2025, Punjab is once again thrust into the eye of India’s long and bitter river water conflicts. Year after year, climate volatility ravages its fertile plains, sweeping away crops and infrastructure despite massive dams and colonial-era barrages. These calamities have laid bare a hard truth: Punjab’s disputes with neighbouring—and now non-riparian—states like Haryana and Rajasthan are no longer just about canal alignments or water-sharing formulas. They have become questions of justice and accountability. And at the heart of this debate, two core issues demand urgent attention.

In the wake of the devastating floods of 2023 and 2025, Punjab is once again thrust into the eye of India’s long and bitter river water conflicts. Year after year, climate volatility ravages its fertile plains, sweeping away crops and infrastructure despite massive dams and colonial-era barrages. These calamities have laid bare a hard truth: Punjab’s disputes with neighbouring—and now non-riparian—states like Haryana and Rajasthan are no longer just about canal alignments or water-sharing formulas. They have become questions of justice and accountability. And at the heart of this debate, two core issues demand urgent attention.

Whether non-riparian states that are drawing water from Punjab’s rivers without paying any royalty should not be made responsible for contributing to compensation when floods ravage Punjab—losses both to crops and to infrastructure—proportionate to the water they consume.

Whether Punjab can lawfully levy a royalty or charge for these waters, and if not, what statutory barriers exist.

The answers to these questions, grounded in constitutional law, statutory provisions and comparative international practice, may hold the key to a new and more just settlement.

The Global Context: How Other Federations Share Flood Losses

Before turning to India’s constitutional framework, it is useful to note how federations and regional groupings elsewhere have approached similar dilemmas. In the European Union, the Solidarity Fund provides financial support to member states struck by major natural disasters, including floods, with contributions flowing not from the affected state alone but from the collective pool. The logic is clear: if integration means common benefits, it must also mean common burdens.

In the United States, flood management and disaster relief are co-funded by federal and state governments. Programmes such as the National Flood Insurance Program, together with federal cost-sharing for infrastructure repair, distribute the fiscal weight of disasters. While the allocations are not calculated on the basis of how much water a downstream or neighbouring state draws, the federal framework ensures that no single state shoulders the burden alone.

International river compacts, such as those on the Danube or the Rhine, also contain clauses requiring riparian states to jointly finance flood-protection works. Though the principles differ, the common thread is that those who benefit from shared rivers cannot absolve themselves when the same rivers bring destruction. This comparative perspective strengthens Punjab’s argument that Rajasthan, Haryana and even Delhi—beneficiaries of Ravi–Beas waters—should share proportionately in the cost of reconstruction.

India’s Constitutional Framework on Water

The Constitution of India distributes legislative competence over water between the Union and the States. Entry 17 of the State List gives states control over water supplies, irrigation and canals within their boundaries, while Entry 56 of the Union List empowers Parliament to regulate and develop inter-State rivers and river valleys if it declares such regulation expedient in the public interest.

Crucially, Article 262 of the Constitution empowers Parliament to make laws for adjudication of disputes relating to inter-State rivers, and permits Parliament to exclude the jurisdiction of the courts over such disputes. Pursuant to this power, Parliament enacted the Inter-State River Water Disputes Act, 1956 (ISRWD Act). It is under this framework that tribunals are constituted to adjudicate claims like those between Punjab and Haryana.

The constitutional position is unequivocal: when rivers cross state boundaries, primacy lies with the Union. States cannot act unilaterally; they can neither enforce their claims through the courts once a tribunal has been constituted, nor impose financial exactions on their neighbours. Punjab’s own attempt to break from this straitjacket—the Punjab Termination of Water Agreements Act, 2004—was struck down in November 2016, when the Supreme Court, in a unanimous 5–0 verdict on a Presidential Reference, declared the legislation unconstitutional. The message could not have been clearer: unilateral state action in matters of inter-State rivers has no constitutional validity.

The Statutory Bar on Royalty or Charges

The direct answer to whether Punjab can levy a “royalty” on Haryana, Rajasthan or Delhi for the waters flowing through its territory is an emphatic no. Section 7 of the ISRWD Act contains a categorical prohibition:

“No State Government shall, by reason of the fact that any works for the conservation, regulation or utilisation of any inter-State river have been constructed within that State, impose any seigniorage or additional rate or fee (by whatever name called) in respect of the use of such water by any other State or the inhabitants thereof.”

This provision has been on the statute book since 1956. Its rationale was to prevent upstream states from holding downstream states to ransom by imposing tolls or charges merely because the physical infrastructure happens to lie within their territory. It is, therefore, not a recent curtailment of Punjab’s rights but an original limitation placed by Parliament.

The effect is stark: Punjab cannot levy any fee, cess or royalty on Haryana, Rajasthan or Delhi for using Ravi–Beas waters. At best, Punjab may recover proportionate operation and maintenance costs for shared infrastructure, but not a price for the water itself.

The First Question: Sharing the Burden of Flood Losses

If royalty is barred, can Punjab nevertheless demand proportionate contributions towards compensation for flood damages? This is a more nuanced question. The statutory bar applies only to charging for the use of water. It does not, in principle, prevent the Union or the beneficiary states from voluntarily agreeing to a cost-sharing arrangement for disaster damages.

Indeed, the very logic of cooperative federalism suggests that if Rajasthan and Haryana have acquired de facto riparian status by virtue of canal systems and allocations, they must also acknowledge a share of the burdens when floods overwhelm Punjab. Otherwise, Punjab suffers dual injustice— a kind of double whammy: denied both control over its waters and relief from their destructive power.

International precedents, as discussed earlier, show that solidarity funds and basin compacts are workable models. India has its own internal analogue in the form of the National Disaster Response Fund, which pools resources from the Centre. Extending this principle to basin-specific funds—perhaps within the Bhakra Beas Management Board (BBMB) framework—could be a path forward.

The Second Question: Can Punjab Charge Royalty?

The legal position is unequivocal: Punjab cannot charge royalty for water under current law. Section 7 of the ISRWD Act forecloses this possibility, and no amendment since has altered that position. The lapsed Inter-State River Water Disputes (Amendment) Bill, 2019, sought to streamline tribunal processes but did not disturb this prohibition.

Thus, Punjab’s case cannot be built on the language of “royalty.” Instead, it must be reframed as a demand for equitable burden-sharing in disaster relief, separate from the statutory prohibition on charging for water use. That distinction is vital if the claim is to be both legally defensible and politically persuasive.

Towards a New Deal: The Centre’s Mediating Role

What, then, is the way out of this impasse—particularly in a scenario where the Indus Waters Treaty itself has been put in abeyance? The contours of a fair solution must now rest on three clear pillars:

1. Linking the Domestic and International Contexts

In the wake of the Pakistan-abetted Pahalgam massacre, the Government of India has already announced that the Indus Waters Treaty is being held in abeyance. This is a momentous assertion of India’s sovereign rights over the rivers of the Indus system, espcially the western rivers of Indus, Jhelum and Chenab. If the Union can revisit treaty obligations with Pakistan in the face of external aggression, then equity demands with equal force a parallel correction—and a thorough reassessment—of long-standing injustices within the Indian Union itself. Punjab’s grievances over its river waters cannot be separated from this broader sovereign framework; they must form part of the same assertion of national will and constitutional fairness.

2. A Central Compact on Flood-Risk Sharing

Against this backdrop, the Union Government should facilitate a basin-level compact among Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan and Delhi under its powers in Entry 56 and Article 262. Such an agreement must provide for permanent, proportionate cost-sharing of flood protection, disaster relief, and reconstruction of damaged infrastructure. This would ensure that the states who draw sustenance from Punjab’s rivers also shoulder responsibility when those rivers unleash devastation.

3. A Standstill on Contentious Projects

Pending such a settlement, it would be both just and prudent for the Union Government to request the Supreme Court to adjourn sine die Haryana’s petition for the expeditious completion of the Sutlej–Yamuna Link (SYL) Canal. To press ahead with the project while Punjab reels from repeated floods would deepen the inequities of the past. A judicial standstill would create the breathing space necessary for negotiation, rather than confrontation.

Undoing the Series of Injustices

Punjab has long borne the brunt of national policies that have treated it as a mere water reservoir for others. From the diversion of river waters to the imposition of centralised allocations, Punjab’s rights and burdens have been unequally distributed since Independence. The floods of 2023 and 2025 have now brought the costs of this inequity into sharp relief. Farmers are devastated, roads and canals lie broken, and yet the states that draw Punjab’s waters pay nothing towards rebuilding.

It is time to undo this pattern of injustice. Punjab does not seek charity but fairness: if its rivers irrigate fields in Rajasthan, quench the thirst of Haryana, and sustain Delhi, then those very states must stand with Punjab when the rivers turn destructive.

The Way Forward: Towards Justice in Water Federalism

The debate is no longer only about allocations or the SYL Canal. It is about justice in Indian federalism. Two issues are central. First, whether non-riparian beneficiaries of Punjab’s rivers should contribute proportionately to compensation when floods devastate Punjab. International practice, comparative federalism, and principles of solidarity all say yes. Second, whether Punjab can charge royalty for its waters. Statutory law says no, and has said so since 1956.

The way forward is a new deal, mediated and guaranteed by the Central Government. If necessary, Parliament can even enact a special law pertaining to the Indus basin to actualise this framework, anchoring both domestic equity and sovereign control. By forging a basin-level compact for flood-risk sharing, by seeking a judicial standstill on the SYL case, and by linking inter-state justice with the broader recalibration of the Indus Waters Treaty, the Centre can finally address Punjab’s long-standing grievances. Such a course would not only be fair, just and equitable, but would also recognise the immense sacrifices Punjab has made since Independence and restore a measure of balance to India’s troubled water federalism.