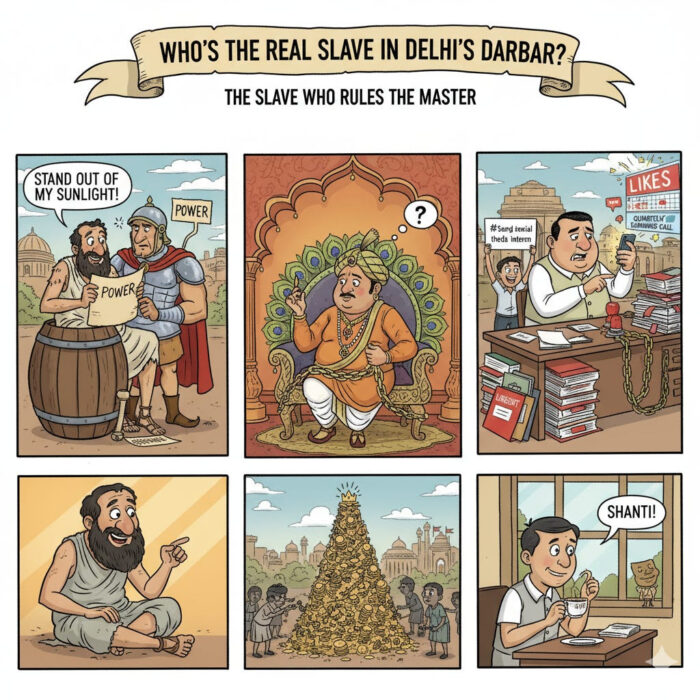

The Greek philosopher Diogenes of Sinope had a wicked sense of humour when it came to power. He lived in a barrel, begged for food, and once told Alexander the Great—the man who conquered half the known world—to “stand out of my sunlight.” If anyone could puncture pomposity, it was him. Among his many paradoxes, one still hits home today:

The Greek philosopher Diogenes of Sinope had a wicked sense of humour when it came to power. He lived in a barrel, begged for food, and once told Alexander the Great—the man who conquered half the known world—to “stand out of my sunlight.” If anyone could puncture pomposity, it was him. Among his many paradoxes, one still hits home today:

“The art of being a slave is to rule one’s master.”

At first, it sounds like an instruction manual for sycophants. But Diogenes despised sycophancy; he was the last man to butter anyone up. What he meant was sharper: masters often look powerful, but they are chained to their appetites, their comforts, and their egos. The slave who knows these chains can tug them. The master, in truth, is the captive.

Diogenes and the Joke of Power

To Diogenes, freedom wasn’t about legal status; it was about inner independence. The slave who could survive on scraps in the open air was freer than the master who couldn’t sleep without silk sheets. When Alexander offered him any gift, Diogenes asked only for sunshine. The conqueror looked suddenly small next to a man who wanted nothing.

Marcus Aurelius: The Emperor Admits His Chains

Centuries later, Marcus Aurelius, emperor of Rome, scribbled in his diary (Meditations) that he too was enslaved—not by barbarians or rivals, but by himself. He scolded his own mind for being “a slave to the book, to pride, to the need for applause.”

Here was the most powerful man of his age, commander of legions, ruler of half the world, confessing that he was captive to cravings no different from ours. From barrel to throne, the lesson was clear: masters are often the most tightly bound.

Birbal: India’s Answer to Diogenes

If Greece had its Cynics and Stoics, India had Birbal. Emperor Akbar, lord of the Peacock Throne, may have ruled over half of Hindustan, but he was routinely disarmed by his courtier’s wit.

When Akbar asked him to count the crows in Agra, Birbal replied with straight-faced confidence: “As many as you say, Jahanpanah. If more, they’re visiting relatives; if fewer, they’ve gone to see family elsewhere.” The emperor of armies was suddenly the pupil, not the master.

When pressed to name the most precious thing in the world, Birbal produced a grain of wheat. Empires could be built or broken, but without food, even the Peacock Throne meant nothing. Akbar laughed—but the truth bit hard.

Birbal, like Diogenes, excelled in showing that those who appear to command are themselves commanded by subtler chains.

From Agra to New Delhi: The Modern Darbar

The paradox has not aged a day. Step into Lutyens’ Delhi and you will find netas and babus bound by invisible ropes as tightly as any Roman emperor or Mughal king.

Take the neta. He thunders from the podium about self-reliance, but checks Twitter ten times a day to count likes on his latest speech. He claims to lead the people, yet he cannot sleep until his media manager assures him that primetime anchors found his soundbites “hard-hitting.” He is less the master of the masses than the slave of the newsroom.

Or the babu, perched like a minor emperor behind a wall of files. He terrifies junior officers with his red pencil, but shift his lunch break or delay his chai, and the empire totters. In truth, the darbar depends less on the senior-most secretary and more on the peon who knows when to fetch the samosa.

Even our corporate captains aren’t spared. They boast of global reach, but are prisoners of the Sensex, of quarterly earnings calls, of the dreaded PowerPoint deck. Diogenes would laugh; Birbal would raise an eyebrow.

The Real Masters and Slaves

In Delhi today, the true masters are rarely the ones with the Z-security convoys. They are the pollsters who whisper numbers into the ears of netas, the bureaucrats who draft that crucial note, the social media interns who know which hashtag is trending. The emperors of our age are still ruled—not by philosophy, perhaps, but by optics.

Meanwhile, the clerk who eats his home-cooked lunch with satisfaction, the driver who hums Kishore Kumar in traffic, the retired teacher who walks in the park without checking WhatsApp forwards every five minutes—these may be the true masters, free of need and anxiety.

The Punchline

Diogenes mocked Alexander, Marcus mocked himself, Birbal mocked Akbar. Each showed, in his own way, that the throne is no guarantee of freedom. Masters are captives of desire; slaves, courtiers, philosophers may hold the real key.

So, the next time you see a minister trembling at an opinion poll, or a babu sulking without his chai, remember Diogenes’ paradox. The crown doesn’t make the master; freedom from craving does. Sip your chai in peace—that, perhaps, is the highest form of rule.