As India observes Parakram Diwas today on the 129th birth anniversary of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, the nation pauses to honour one of its most enigmatic and fearless freedom fighters. Yet, beneath the patriotic commemorations lies a troubling paradox: eight decades after his reported death, India still grapples with fundamental questions about what truly happened to the man who electrified millions with his call of “Give me blood, and I will give you freedom.” More disturbingly, the soldiers who fought under his command in the Indian National Army returned to an independent India that offered them neither honour nor adequate recompense—a historical injustice that remains inadequately addressed even today.

As India observes Parakram Diwas today on the 129th birth anniversary of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, the nation pauses to honour one of its most enigmatic and fearless freedom fighters. Yet, beneath the patriotic commemorations lies a troubling paradox: eight decades after his reported death, India still grapples with fundamental questions about what truly happened to the man who electrified millions with his call of “Give me blood, and I will give you freedom.” More disturbingly, the soldiers who fought under his command in the Indian National Army returned to an independent India that offered them neither honour nor adequate recompense—a historical injustice that remains inadequately addressed even today.

The Revolutionary Who Challenged Empire

Born on January 23, 1897, in Cuttack, Odisha, Subhas Chandra Bose emerged as a towering figure in India’s independence movement, distinguished by his radical approach that stood in sharp contrast to Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent resistance. After topping the Indian Civil Services examination, Bose made the audacious decision to resign from the coveted position, dedicating himself entirely to the cause of complete independence—not the dominion status that satisfied many of his contemporaries.

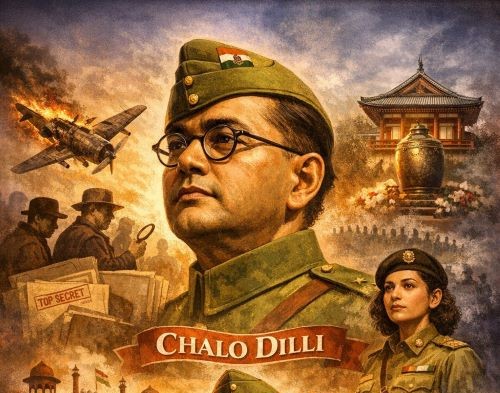

Bose’s ideological trajectory took him from the presidency of the Indian National Congress in 1938 to a dramatic break with the Gandhian establishment in 1939, when fundamental disagreements over strategy compelled him to form the Forward Bloc. His conviction that armed resistance was indispensable for dislodging the British led him on an extraordinary journey—escaping British surveillance, travelling through Germany and Japan, and ultimately forming the Provisional Government of Azad Hind on October 21, 1943. Under his leadership, the Indian National Army, reconstituted from Indian prisoners of war and expatriates in Southeast Asia, launched a military campaign under the rallying cry “Chalo Dilli”—March to Delhi.

What distinguished Bose’s INA was not merely its military ambition but its revolutionary social composition. In an era when the British Indian Army segregated soldiers by religion and caste, the INA brought together Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, and people from all regions under one banner. The Rani of Jhansi Regiment, led by Captain Lakshmi Sahgal, stood as one of the world’s first all-women combat units, embodying Bose’s progressive vision of gender equality. This remarkable unity across religious and communal lines would later manifest powerfully during the Red Fort trials, when Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs demonstrated together in unprecedented solidarity for the INA officers—a final testament to composite nationalism before the tragedy of Partition.

The Mystery That Refuses to Die

The official narrative maintains that on August 18, 1945, Netaji died from third-degree burns sustained when a Japanese bomber aircraft crashed shortly after take-off from Taihoku (present-day Taipei) in Taiwan. According to this version, Bose, soaked in gasoline, was transported to Nanmon Military Hospital where he succumbed to his injuries that evening. His body was allegedly cremated, and the ashes deposited at the Renkoji Temple in Tokyo.

Yet from the very beginning, this account has been contested. Three government-appointed inquiry commissions over six decades yielded contradictory findings. The Shah Nawaz Committee (1956) and the Khosla Commission (1970) both concluded that Bose died in the plane crash. However, the Justice Mukherjee Commission, constituted in 1999 and submitting its report in 2005 after exhaustive investigation, arrived at radically different conclusions: Netaji did not die in the plane crash as alleged, and the ashes preserved in the Renkoji Temple were not those of Netaji.

The Mukherjee Commission’s findings were buttressed by extraordinary evidence. The Taiwan government officially informed the Commission that there was no record of any aircraft crash at Taihoku Airport—or anywhere in Taiwan—between August 14 and September 20, 1945, a period spanning five weeks around the supposed date of the crash. This testimony was corroborated by U.S. intelligence reports that confirmed no such crash occurred on that date. The only cremation recorded at the Taihoku crematorium during that period was of a Japanese national named “Ichiro Okura” with serial number 2641—with detailed documentation of his date of birth, residential address, and death by heart failure, but absolutely no reference to Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose.

Even more intriguing is the controversy surrounding the Renkoji Temple ashes. Recent translations of correspondence between the temple’s chief priest and Indian authorities revealed that permission for DNA testing was explicitly granted in 2005. However, the Mukherjee Commission’s official English translation omitted crucial paragraphs from the Japanese original, instead claiming that “on account of the Temple Authorities’ reticence… the commission could not proceed further”. The chief priest’s actual words—“I agreed to offer my cooperation for the testing”—were never made public. Despite repeated requests from Bose family members, including his daughter Anita Bose Pfaff, to Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2016 and 2019 for DNA testing to bring closure to the matter, no tests have been conducted.

The absence of a plane crash has given rise to alternative theories. The most prominent suggests that Bose escaped to Soviet-controlled Manchuria, seeking Stalin’s assistance for India’s liberation, but was instead imprisoned in Siberian gulags—possibly dying in captivity around 1953. Declassified documents refer to Nehru–Stalin correspondence from October 1946 mentioning Bose “in the present tense” and his presence in the USSR. Another theory holds that Bose survived Soviet imprisonment and returned to India, living incognito as “Gumnami Baba” in Faizabad, Uttar Pradesh, until his death in 1985. When Gumnami Baba’s room was examined after his death, investigators discovered old family photographs of the Bose family, letters from INA leaders, German binoculars, and books about Netaji—articles incongruous for a wandering ascetic.

The Files That Won’t Be Opened

The controversy over Bose’s disappearance has been compounded by successive governments’ refusal to fully declassify documents related to him. For decades, both the UPA and NDA governments maintained that releasing these files would “prejudicially affect relations with foreign countries,” endanger internal security, and potentially spark unrest in Bengal. The arguments against declassification cited national security concerns and the sensitivity of diplomatic relations.

When Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced in October 2015 that files would be declassified—declaring that “a country which forgets its history cannot create history”—it marked a significant symbolic shift. Beginning in December 2015, the government released files in batches: the first 33 files from the Prime Minister’s Office, followed by 37 from the Ministry of Home Affairs and files from the Ministry of External Affairs, totalling approximately 100 files publicly released by January 23, 2016.

However, activists from Mission Netaji and Bose family members have pointed out that the declassified files contained limited substantive information about the actual circumstances of Netaji’s disappearance. Of the 33 PMO files initially released, only ten related directly to Bose’s disappearance, with fourteen concerning the formation and working of the three inquiry commissions. Most files were created decades after 1945—during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s—and had already been examined by the Mukherjee Commission without yielding breakthrough evidence. Five sensitive files remain withheld, reportedly containing information that might “hurt sentiments” or relate to Netaji’s widow and daughter.

The transparency deficit extends beyond India’s borders. Japan continues to withhold three classified files on Netaji despite multiple requests from the Indian government. When External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj approached Japan in 2017, the response stated that documents are declassified according to internal policies and no exception could be made for India. Russia has consistently maintained that no documents related to Netaji exist in their archives, even after additional investigations. The United States declined to conduct “extensive document research” through multiple agencies, citing resource constraints. Only the United Kingdom has posted 62 files on Bose on public websites.

Perhaps most disturbing is evidence that the Indian government maintained surveillance on the Bose family until 1968—twenty-three years after Netaji’s supposed death in 1945. If the government believed Bose had died in 1945, what justified monitoring his family for another two decades? Declassified files reveal that Intelligence Bureau officials intercepted and copied letters from Netaji’s widow Emilie Schenkl in Vienna to family members in India, placing these letters in secret files for over half a century. This colonial practice of surveillance continued seamlessly into the post-colonial state, suggesting that either elements within the government doubted the plane crash narrative or harboured fears about Bose’s potential return.

The arguments in favour of complete declassification are compelling. International democratic norms dictate that government files should be opened after 25–30 years, with all files declassified after 50 years. More than 80 years have elapsed since 1945, and by any reasonable standard, whatever diplomatic sensitivities existed should have long dissipated. The release of the Nixon papers revealed American plans to deploy the USS Enterprise against India in 1971, yet this disclosure did not permanently damage Indo–U.S. relations. Logically, information about a leader from a bygone era should not threaten contemporary diplomatic ties.

The official justifications for continued secrecy appear increasingly hollow. If Bose indeed died in 1945 as claimed, what foreign policy implications could possibly remain sensitive eight decades later? The persistence of classification suggests that the files may contain information not about Bose himself, but about the actions—or inactions—of post-Independence governments and their relationship to his fate. As scholar and former diplomat Shashi Tharoor has argued, these files may reveal “dishonourable things done by some in the upper echelons of India’s post-Independence government” rather than definitive answers about Netaji.

The Forgotten Soldiers

If the mystery of Netaji’s fate represents an unresolved historical question, the treatment of INA soldiers after Independence constitutes a documented betrayal. When approximately 26,000 INA personnel surrendered to British forces in 1945, they faced immediate classification: “Whites” (loyal to the Crown) were retained, “Greys” were watched, “Dark Greys” were detained, and “Blacks” (considered traitors) faced court-martial. Initially 7,600 were slated for trial; this number was eventually reduced to approximately 600.

The Red Fort trials of late 1945 and early 1946 became a watershed moment in India’s freedom struggle. When Colonel Shah Nawaz Khan, Colonel Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon, and Major General Prem Sahgal—a Muslim, a Sikh, and a Hindu—were tried together for waging war against the King-Emperor, the spectacle ignited unprecedented nationwide protests. The Indian National Congress, previously lukewarm toward the INA, recognised the political significance and organised their legal defence, with Jawaharlal Nehru, Bhulabhai Desai, and other luminaries arguing their case. The three officers were convicted and sentenced to transportation for life, but following massive public demonstrations and concerns about civil disorder, the British Commander-in-Chief remitted the sentences.

The INA trials catalysed India’s march toward Independence by galvanising public sentiment, unifying communities across religious lines, and demonstrating the fragility of British authority. Demonstrations erupted across the country, strikes paralysed cities, and even elements of the Royal Indian Air Force and Indian Navy showed signs of wavering loyalty. Many historians argue that the INA trials and their aftermath convinced the British that the Indian armed forces could no longer be relied upon to maintain colonial rule, hastening the decision to grant Independence in 1947.

Yet when Independence finally arrived, the INA soldiers found themselves unwelcome in the very nation they had fought to liberate. Field Marshal K.M. Cariappa, the first Indian Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army, opposed integrating INA personnel, citing concerns about discipline, military cohesion, and morale. This decision deprived INA veterans of official recognition and the career opportunities their erstwhile adversaries in the British Indian Army enjoyed. The rationale—that INA soldiers had broken their oath of allegiance—ignored the fundamental moral distinction between loyalty to a colonial oppressor and loyalty to one’s own nation’s freedom struggle.

The financial treatment was equally inadequate. Many INA veterans were denied pensions entirely and had to wage protracted legal battles for minimal financial relief. It was not until 1963—sixteen years after Independence—that the government sanctioned a paltry package of Rs. 30 lakhs (Rs. 3 million) for all INA veterans. Recognition as “freedom fighters” eligible for state pensions came inconsistently and often far too late. Captain Ram Singh Thakur, who composed the stirring INA anthem “Kadam Kadam Badhaye Ja” (adopted later by independent India’s military), initially faced rejection of his freedom fighter status and pension claims.

To be sure, a handful of senior INA leaders received prominent appointments. Shah Nawaz Khan served as Union Minister for Railways and was elected four times to the Lok Sabha. Abid Hasan became an ambassador, and Captain Lakshmi Sahgal pursued a career in left-wing politics, eventually becoming the Left parties’ presidential candidate in 2002. But these high-profile exceptions served to obscure the struggles faced by thousands of rank-and-file soldiers who returned to civilian life without honour, pension, or support.

The Swatantrata Sainik Samman Pension Scheme, introduced in 1972, theoretically covered freedom fighters including INA personnel. However, eligibility criteria were restrictive, requiring documented proof of imprisonment or suffering that many INA soldiers could not produce. Of the 171,689 freedom fighters who have received central pensions under the scheme since its inception, only 13,212 are still alive today receiving benefits. In 2016, the Modi government raised the monthly pension for freedom fighters from Rs. 21,395 to Rs. 26,000—a gesture more symbolic than substantive given the escalating cost of living and the advanced age of surviving veterans.

The contrast with Pakistan is instructive. Pakistan absorbed INA soldiers into its armed forces after Partition. India’s refusal to do the same reflected not just Field Marshal Cariappa’s institutional concerns but perhaps deeper political anxieties. There is speculation that the political establishment feared that battle-hardened, ideologically motivated INA veterans might challenge the dominance of the Congress party or prove difficult to control. Whether such fears were justified is debatable, but their effect was to leave the INA’s foot soldiers—who had risked everything for India’s freedom—as second-class citizens in the nation they had fought to create.

India’s treatment of INA veterans represents a broader pattern of historical neglect. Comprehensive memorials or museums dedicated to the INA’s legacy remain inadequate. Educational curricula provide insufficient coverage of the INA’s contributions, depriving future generations of a complete understanding of their sacrifice. Documentation of INA soldiers’ experiences has been scattered and incomplete. This institutional amnesia perpetuates injustice and impoverishes national memory.

A Legacy for Today’s India

As India observes Parakram Diwas (Day of Valour) in 2026, declared by the Modi government in 2021 to commemorate Netaji’s 125th birth anniversary, his legacy assumes renewed relevance. In an era of rising communalism and fractured national unity, Netaji’s vision of an inclusive, secular India offers critical lessons. His INA demonstrated that Indians of all faiths could unite for a common cause, transcending the sectarian divisions that the colonial administration had assiduously cultivated. As he stated in Tokyo in November 1944: “The Government of Free India must have an absolutely neutral and impartial attitude towards all religions and leave it to the choice of every individual to profess or follow a particular religious faith”.

Bose’s economic vision remains equally pertinent. At a time when India aspires to become a developed nation by 2047, Netaji’s emphasis on state-led industrialisation, comprehensive economic planning, and self-reliance resonates powerfully. Through the National Planning Committee proposals and his advocacy for heavy industries as the backbone of national development, Bose articulated a roadmap for economic sovereignty that anticipated elements of India’s post-Independence planning. His synthesis of socialist principles with nationalism—seeking rapid industrialisation while ensuring equitable distribution and social justice—offers a framework for addressing contemporary challenges of poverty, unemployment, and inequality.

Bose’s commitment to women’s empowerment, evident in the formation of the Rani of Jhansi Regiment, challenges modern India to fulfil constitutional promises of gender equality. His opposition to caste discrimination—exemplified by his spending weeks nursing a Dalit classmate suffering from cholera during his student days—provides a moral foundation for ongoing struggles against social hierarchy. His vision of a “planned economy” addressing unemployment and poverty through scientific industrialisation and agrarian reform speaks directly to India’s unfinished development agenda.

For India’s youth, navigating an age of distractions and instant gratification, Netaji’s life exemplifies disciplined commitment to long-term ideals over short-term gains. His resignation from the Indian Civil Service to join the freedom movement demonstrates the courage to prioritise values over personal advancement. His famous exhortation—“Give me blood, and I will give you freedom”—remains a call to national service that transcends generations.

Yet the contradictions persist. The same government that celebrates Parakram Diwas with patriotic fervour has been unable or unwilling to resolve the fundamental questions about Netaji’s fate through comprehensive declassification and DNA testing of the Renkoji ashes. The INA soldiers who embodied Netaji’s ideals received inadequate recognition and recompense, and today’s defence personnel continue to navigate bureaucratic indifference regarding pension and disability benefits. The secular, pluralistic vision that Bose championed stands in tension with contemporary political movements that seek to impose religious conformity.

Conclusion: The Nation’s Duty

As we mark Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s 129th birth anniversary, India confronts an uncomfortable truth: the nation has yet to fully honour the man or the movement he led. Eight decades after his reported death, we still lack definitive answers about his fate, despite evidence that contradicts the official narrative. The soldiers who fought under his command in the INA were systematically marginalised despite their contributions to hastening Independence. And the values he championed—secularism, inclusivity, social justice, and self-reliance—remain aspirational rather than fully realised.

The path forward requires concrete action. Complete declassification of all files related to Netaji held by India and foreign governments, without exception, would demonstrate genuine commitment to historical transparency. Conducting DNA tests on the Renkoji ashes, with family consent, could finally resolve decades of speculation. Establishing comprehensive INA memorials and museums would preserve their legacy for future generations. Integrating the INA’s story more prominently into educational curricula would ensure that young Indians understand the diversity of strategies and sacrifices that secured their freedom. And enhanced benefits for surviving INA veterans and their families would constitute long-overdue material recognition.

These measures would not merely settle historical debates; they would reaffirm fundamental democratic principles. A government secure in its legitimacy has nothing to fear from historical truth, however uncomfortable. A nation mature enough to confront the complexities of its past—including the failures and betrayals alongside the triumphs—builds a stronger foundation for its future.

Netaji believed that freedom was only the beginning—that the real challenge lay in building a strong, self-reliant, equitable India worthy of the sacrifices made to achieve Independence. As India aspires to global leadership in the twenty-first century, it must reckon with these unfinished obligations to Netaji and the INA soldiers. Only then can we truly honour the spirit of Parakram Diwas and embody the courage, integrity, and commitment to truth that Netaji exemplified throughout his extraordinary life.