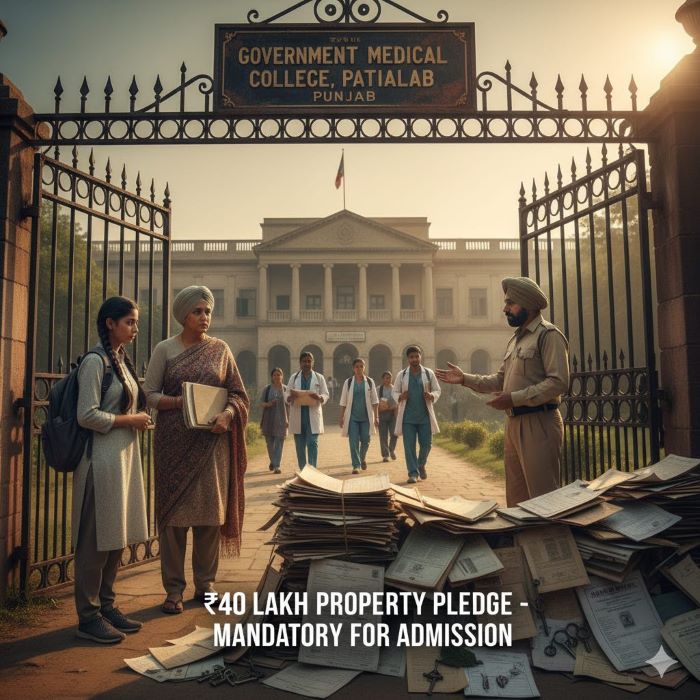

Picture a teenager from a small town in Punjab who has cleared PMT, the gruelling medical entrance exam. Her parents, modestly salaried schoolteachers, own a single flat under mortgage. Despite winning a government MBBS seat, she cannot begin her classes until her family pledges two immovable properties worth ₹40 lakh in total. Lacking such collateral, her hard-won opportunity is at risk.

Picture a teenager from a small town in Punjab who has cleared PMT, the gruelling medical entrance exam. Her parents, modestly salaried schoolteachers, own a single flat under mortgage. Despite winning a government MBBS seat, she cannot begin her classes until her family pledges two immovable properties worth ₹40 lakh in total. Lacking such collateral, her hard-won opportunity is at risk.

The Policy Shift in Punjab

This is the result of Punjab’s newly introduced regime: either serve two years in government facilities after MBBS or pay ₹20 lakh, secured by pledging two properties at admission. Government Medical Colleges are already issuing ultimatums that non-compliant students will be barred from class. On paper, this is meant to ensure doctors give back to the public system. In practice, it imposes a wealth test disguised as policy.

Legitimacy of Public Service Bonds

The State’s intention is understandable. Rural Punjab suffers a chronic shortage of doctors. Taxpayers subsidise medical education, and it is reasonable to expect service in return. Courts have upheld service bonds in principle, provided they are reasonable. But the method of enforcing the bond is what matters—and Punjab’s approach is strikingly inequitable.

The Problem of a Property Pledge

Requiring two immovable properties excludes precisely those students whom affordable medical education is supposed to help. Many families—urban middle class with a single apartment, tenant households, small farmers with encumbered land, or first-generation professionals, not to mention landless families or the SCs—simply cannot comply. For them, this is not a deterrent but a dead end. The pledge does not measure merit or willingness to serve; it measures family wealth.

The Myth of Affordability

By insisting on a ₹40-lakh collateral, the State effectively exacts a hidden price for education. Tuition may remain low on paper, but the true entry cost is ownership of substantial assets. This is a quiet retreat from the promise of affordable, merit-based access to public education. It risks shrinking the pool of doctors from disadvantaged groups and entrenching privilege.

Policy Without Political Wisdom

The harshness of this policy betrays its origins. It seems less the product of an enlightened, people-sensitive Cabinet decision and more the handiwork of a myopic bureaucrat, acting on the advice of senior medical specialist and doctors placed in administrative roles. No politician truly rooted in the soil—aware of the financial realities of families in villages and small towns—would reasonably endorse such an onerous requirement. For an elected leader, the optics of locking opportunity behind a ₹40-lakh property pledge would be politically suicidal. This bears the unmistakable stamp of administrative insularity rather than democratic wisdom.

Alternatives That Work

Enforcing service need not be punitive or exclusionary. Other states and sectors rely on flexible security tools:

Bank guarantees

Fixed deposit liens

Insurer-issued surety bonds

Income-linked repayment plans

Such instruments are transparent, proportionate, and accessible. They don’t demand multiple title deeds at the point of admission. Having said that, even these would be a difficult condition to fulfil especially for the economically backward families.

Why Doctors Resist Bonded Service

The real obstacle is not students’ unwillingness to serve but the conditions of service. Young doctors often face poor housing, unsafe postings, irregular stipends, and lack of mentorship. Bonds that threaten punishment do not fix these systemic problems. If the State offered safe housing, fair pay, professional respect, and PG admission incentives, compliance would rise naturally.

Bonded Labour or Not?

Strictly legally, this policy may not amount to bonded labour, as courts distinguish service bonds from forced labour. But ethically, demanding property pledges at admission feels coercive. Families are compelled to mortgage their future on pain of exclusion. That resembles economic compulsion, even if it falls short of the statutory definition of bonded labour.

A Better Design Is Possible

A sensible framework would:

Replace property pledges with flexible financial instruments.

Right-size the bond amount to reflect the actual subsidy per student.

Provide means-tested relaxations for economically weaker families.

Improve rural postings to make service desirable, not punitive.

Offer humane exit options—grace periods, instalments, and appeal mechanisms.

The Moral Test of Policy

The true test of a policy is how it treats the weakest candidate who still deserves a chance. By erecting a ₹40-lakh barrier, Punjab fails that test. The State can uphold its goal of rural service without excluding the poor or middle class. It must roll back the property pledge requirement, redesign the bond regime, and create a system that draws doctors into service willingly.

In Summary: Roll Back, Redesign, Rebuild

Punjab has an opportunity to show leadership in how it balances public investment with public return. Bonds, if designed well, can serve both students and patients. But this current model—an inequitable, asset-heavy barrier—undermines both equity and effectiveness. The State must choose: does it want to build a proud, motivated cadre of public doctors, or does it want to lock the gates of opportunity behind a wall of property papers?