The 2027 Punjab Assembly election marks a turning point in how political communication is crafted, consumed, and judged. What once relied on the strength of public meetings, grassroots credibility, and long-term engagement with communities has now shifted into a digital arena where aesthetics often overshadow substance. Instagram, once a platform for personal expression, has quietly transformed into a political battleground one where filters, transitions, and curated visuals compete with real issues for public attention.

The 2027 Punjab Assembly election marks a turning point in how political communication is crafted, consumed, and judged. What once relied on the strength of public meetings, grassroots credibility, and long-term engagement with communities has now shifted into a digital arena where aesthetics often overshadow substance. Instagram, once a platform for personal expression, has quietly transformed into a political battleground one where filters, transitions, and curated visuals compete with real issues for public attention.

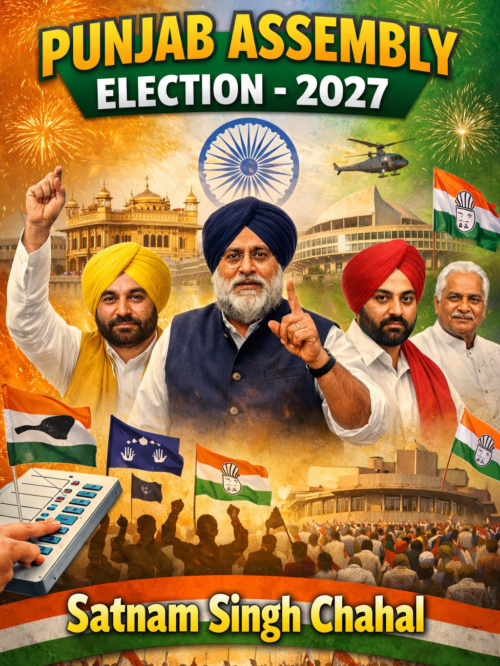

Across Punjab, candidates are discovering that their political identity is no longer shaped primarily by their work on the ground but by the visual narrative they construct online. A well-lit photograph at a village event can travel farther than the event itself. A 15‑second reel summarizing a day’s activities can overshadow months of policy planning. The metrics that matter most—views, likes, shares, and engagement—have become the new currency of political relevance.

This shift raises uncomfortable but necessary questions. When political messaging is optimized for virality rather than clarity, what happens to the depth of public discourse? When a candidate’s popularity is measured by algorithmic reach rather than community trust, what becomes of democratic accountability? And when the line between influencer culture and political leadership blurs, how does the voter distinguish between performance and purpose?

Punjab’s youth, deeply immersed in digital culture, are both the drivers and the critics of this transformation. They appreciate creativity, speed, and innovation, but they also understand the limitations of a politics built on curated imagery. A reel can highlight a problem, but it cannot solve it. A trending hashtag can spark a conversation, but it cannot replace sustained governance. The tension between online visibility and offline responsibility is becoming increasingly visible in this election cycle.

The new digital-first campaign model has also changed how political promises are packaged. Manifestos, once detailed documents outlining long-term plans, are now condensed into bite-sized visuals designed for quick consumption. Complex issues are simplified into slogans. Nuanced debates are replaced by catchy captions. The pressure to remain constantly visible online pushes candidates to prioritize content creation over community engagement.

Yet, beneath the surface of this digital spectacle lies a deeper truth: voters still care about real issues. They may enjoy the creativity of a candidate’s social media presence, but they ultimately judge leadership by actions, not aesthetics. The Instagram era may have changed the language of political communication, but it has not erased the expectations of governance.

As Punjab moves through the 2027 election season, the contrast between digital performance and ground reality is sharper than ever. The challenge for candidates is not merely to master social media but to ensure that their online persona aligns with their real-world commitments. The challenge for voters is to look beyond the filters and evaluate the substance behind the spectacle.

In the end, the rise of Instagram politics is neither entirely good nor entirely harmful. It is a reflection of a changing society—one that values speed, visibility, and creativity, but still demands sincerity, accountability, and results. The future of Punjab’s democracy will depend on how well both leaders and citizens navigate this new terrain, balancing the power of digital storytelling with the enduring need for genuine public service.

In the 2027 campaign season, a new rule has emerged:

“If it doesn’t become a reel, it doesn’t become an issue.”

Candidates no longer visit villages to solve problems; they visit to find “aesthetic backgrounds” for their next post.

A villager asks, “Sir, when will our road be repaired?”

The candidate replies, “As soon as we get a good transition shot.”

Campaign offices don’t print posters anymore.

Instead, they hold meetings to decide:

“Which filter gives the strongest leadership vibe?”

Earlier, politicians met people.

Now people are told,

“Please look into the camera; this clip goes up tomorrow.”

Manifestos don’t come as PDFs.

They arrive as 15‑second reels with captions like:

“Punjab, but make it aesthetic.”

If this trend continues, the next election might replace EVMs with Instagram polls:

“Swipe up to vote for your MLA.”