Recently, my mother-in-law underwent a knee replacement surgery at a leading hospital in Mohali under the ECHS scheme. Since she needed assistance for a month or so during her recovery, the hospital helpfully referred us to a few agencies that provide attendants—women with verified antecedents and basic training in adult care. These were not qualified nurses or even nursing students, but ordinary girls who had acquired some experience in looking after post-operative and elderly patients.

Recently, my mother-in-law underwent a knee replacement surgery at a leading hospital in Mohali under the ECHS scheme. Since she needed assistance for a month or so during her recovery, the hospital helpfully referred us to a few agencies that provide attendants—women with verified antecedents and basic training in adult care. These were not qualified nurses or even nursing students, but ordinary girls who had acquired some experience in looking after post-operative and elderly patients.

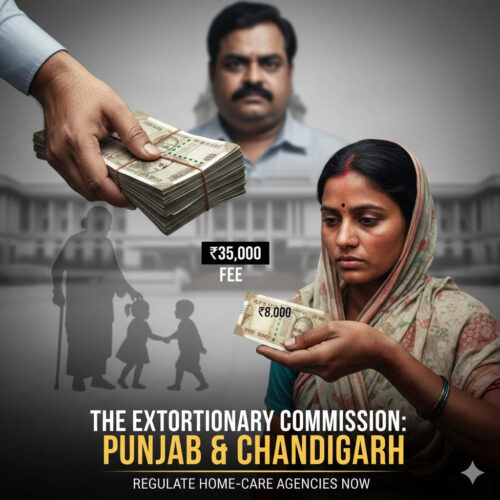

What truly shocked us was the financial arrangement: while the agency charged between ₹30,000 and ₹35,000 per month, the caregiver herself received barely ₹8,000 or ₹9,000. The same story is playing out across Chandigarh and the Tricity region, where more and more young mothers are hiring full-time in-residence maids through agencies that charge as much as ₹30,000 a month—yet pay the worker no more than ₹11,000 or ₹12,000. Many of these women even refuse to accept higher, direct payment from employers, explaining that their jobs are temporary and that once an agency blacklists them, they have nowhere else to go.

The Legal Landscape: Full of Gaps

India’s labour regime is expansive but misaligned with the realities of home-based care.

The Contract Labour (Regulation & Abolition) Act, 1970 governs outsourcing and contract work, but it was crafted for factories and institutions—not private homes. The law’s focus on “principal employers” and “establishments” doesn’t easily extend to individual households.

If agencies recruit caregivers across state lines, the Inter-State Migrant Workmen Act, 1979 technically applies, obliging registration, wage parity with locals, and travel allowances. In practice, none of this is followed.

The Minimum Wages framework exists at the state and Union Territory level. Punjab and Haryana have notified schedules for unskilled and semi-skilled labour, but “domestic work” as a category is often missing. Chandigarh’s periodic wage notifications also set general floors, but not specific ones for caregivers.

As for DC rates, they’re merely administrative scales for daily wagers hired by government departments. They serve as rough reference points, not as enforceable minimum wages in the private sector.

The bottom line: a caregiver in someone’s home exists outside the formal web of protection.

The Missing Link: The Intermediary

Our laws protect workers in theory, and sometimes employers, but they barely touch the intermediary—the agency that controls who gets work, where, and at what price. That is where the worst distortions occur.

Families think they’re paying fair rates for care. Workers think they have no choice. The intermediary pockets the difference

.

This opaque arrangement flourishes because no statute mandates registration, disclosure, or transparency. Virtually anyone can set up a placement agency, recruit women from poor families or distant states, and sell “care services” to hospitals and homes.

A Blueprint for Reform

Punjab and Chandigarh can lead with a clear, humane framework—one that brings order without strangling supply.

1. Licence Every Agency

No person or company should place a caregiver or domestic worker without a licence from the Labour Department. Licences should require verified worker records, police checks, and standard contracts signed by the worker, agency, and employer.

2. Mandate Full Fee Disclosure

Each invoice must reveal the total charged to the family, the worker’s net pay, deductions, and the agency’s commission. Hidden mark-ups must attract penalties and suspension.

3. Cap Commissions

Set a ceiling of 10–15% on agency commissions. This ensures agencies earn a fair administrative fee while workers retain dignity and households see value.

4. Enforce Minimum Wages Automatically

Tie minimum-wage compliance into the billing system itself. If a booking undercuts the state or UT’s legal floor, the transaction should not be processed.

5. End Blacklists and Bondage

Prohibit “no-hire” or “blacklist” clauses that prevent families from directly employing a caregiver after a fixed period. Instead, allow a one-time transparent placement fee to compensate the agency.

6. Protect Migrant Workers

When recruitment crosses state lines, agencies must comply with all migrant-worker obligations—travel allowance, wage parity, and proof of medical and accommodation facilities.

7. Introduce Escrow and Digital Payments

Family payments should go into an escrow account, released weekly via UPI once service is verified. This guarantees timely wages and reduces exploitation.

8. Prioritise Safety and Accountability

Require background checks for both workers and households, with grievance helplines linked to the labour department and police.

9. Build a Data-Driven Welfare System

Integrate caregivers into the national e-Shram platform and classify them as “platform” or “gig” workers under the Code on Social Security, 2020, ensuring they access future welfare benefits.

The Promise of an “Uber for Care”

Technology can correct what regulation alone cannot. A transparent platform could allow verified caregivers to register, display training badges, and accept assignments directly—just as cab drivers do. Families could see real-time pricing, star ratings, and safety credentials. Payments would flow digitally and transparently.

But this will only work under a strong licensing and disclosure regime. Without regulation, digital platforms risk becoming the same exploitative middlemen in new clothes. The goal must be empowerment, not convenience for the privileged.

A Model Bill for the Tricity

Punjab and Chandigarh could jointly enact a Domestic & Home-Care Intermediation (Regulation) Act, 2025. It would:

Cover every person or firm placing home-care or domestic workers.

Require annual licensing, public disclosure of commissions, and digital tripartite contracts.

Cap commissions at 15% and link payments to minimum wages.

Guarantee grievance redress within 15 days and penalise blacklisting.

Mirror migrant-work protections when applicable.

Mandate periodic reviews to update caps and standards.

Such a law would legitimise a vital service sector, protect women workers, and provide clarity to thousands of households desperate for reliable care.

Families and Hospitals: What They Can Do Now

Even without a new law, families can act responsibly. Demand a written contract showing wages, rest days, and commission splits. Ask for police verification. Refuse opaque billing. Hospitals referring agencies should ensure they work only with licensed, transparent intermediaries.

The Way Forward

At a time when the Central Government, various State Governments, and even political parties are talking about women’s empowerment—transferring doles directly into women’s bank accounts—there exists another, largely invisible class of women who are left entirely unprotected. These are the young girls who, instead of waiting for welfare schemes, choose to earn a dignified livelihood through honest labour, caring for the elderly, the infirm, and the convalescent. Yet, they remain outside the safety net of any central or state law.

This is a vulnerable section that urgently needs recognition and protection. Care work is not cheap—and it shouldn’t be. But the caregiver, not the middleman, deserves the bulk of what families pay. Minimum wages already exist. Migrant-worker safeguards already exist. What’s missing is a law that caps exploitation and compels transparency.

Punjab and Chandigarh can, and should, pioneer that change. Regulate the intermediaries, digitise payments, empower caregivers—and let compassion finally become compliant.