The Indian rupee has breached ₹90 against the US dollar for the first time, settling at ₹90.19 as of early December 2025. This slide has ignited debates: Why is the dollar strengthening amid India’s booming economy? One report highlights the paradox—robust GDP growth juxtaposed with currency depreciation. Is this genuine price discovery, or has the rupee been artificially propped up, unlike China’s deliberate suppression of the yuan to fuel exports? These are valid questions.

The Indian rupee has breached ₹90 against the US dollar for the first time, settling at ₹90.19 as of early December 2025. This slide has ignited debates: Why is the dollar strengthening amid India’s booming economy? One report highlights the paradox—robust GDP growth juxtaposed with currency depreciation. Is this genuine price discovery, or has the rupee been artificially propped up, unlike China’s deliberate suppression of the yuan to fuel exports? These are valid questions.

However, here, I’ll focus on agriculture’s overlooked upside.

India’s economic surge in 2025 is undisputed, with rating agencies like the IMF, Fitch and S&P affirming 7-8% GDP growth while agriculture contributing around 3.5% only. Yet the rupee’s tumble toward ₹90 alarms urban consumers and importers. Beneath the headlines lies a silver lining for farmers: a weaker currency hands them a market-driven edge. If policymakers and regulators seize it wisely, this “currency shock” could spur diversification, lift rural incomes, and slash the import bill draining national reserves.

A depreciating rupee inflates the cost of dollar-denominated imports like edible oils, pulses, fertilizers, and crude. The fallout—higher household bills and fiscal strain—fuels political firestorms. Onion price spikes have toppled governments, underscoring consumers’ clout over producers.

But the indirect benefit? Foreign rivals lose their pricing advantage. Once-cheap imports—yellow peas, lentils, palm oil, sunflower oil, and bulk oilseed meals—now cost more in rupees. This pivots demand to homegrown dals, oilseeds, maize, and sugarcane, bolstering farmgate prices and freeing capital for expansion.

Recent data underscores the stakes: Edible oil imports surged 22% to ₹1.61 lakh crore in the 2024-25 marketing year (November-October), with volumes steady at 16 million tonnes. Pulses imports hit a six-year high in FY25, exposing deep vulnerabilities. A weaker rupee could flip this script, incentivizing domestic ramp-up.

Two realities amplify this pivot’s urgency. First, India’s heavy reliance on imports: Billions in annual outflows for pulses and oils that we could produce. Second, farm policies—from MSP signals to trade barriers—remain reactive and stifled. The 2020 reforms, choked by misinformation, demand revival through inclusive dialogue to reframe them positively.

Ashok Gulati, the eminent agri-economist warns that without shifting incentives from water-guzzling paddy to pulses and oilseeds, India risks importing 80-100 lakh tonnes of pulses by 2030. He advocates crop-neutral incentives and rational tariffs, letting farmers tap global demand unhindered by protectionist whims. A falling rupee supercharges his case threefold: It offers “natural protection” by pricier imports, sans subsidy hikes; enhances ethanol viability as crude costs rise in rupees, aiding sugarcane and maize growers; and boosts export rupee yields for basmati, spices, and value-added goods. Yet these windfalls are fleeting without policy steadiness—export bans, erratic minimum prices, and flip-flop duties erode trust in processing, storage, and crushing infrastructure. (See research links below)

Bhupinder Singh Mann’s parliamentary legacy drives home policy’s weight. As a veteran farmer-leader and Rajya Sabha MP, he relentlessly probed ad-hoc controls, flawed subsidies, and export curbs as “negative subsidies” that crush producer margins while shielding consumers. His numerous questions in Parliament—on fertilizer subsidy hikes (August 1996), paddy procurement (September 1996), and agricultural input imports (August 1996)—mirror today’s fray. Mann’s sole voice for farmers in Parliament echoes a timeless plea: unpredictable policies hurt farmers; reforms and stability can secure their future. (See research links below).

Echoing this is the late Sharad Joshi, the farmer iconoclast who rejected perpetual handouts. Joshi decried “negative subsidies”—state meddling via controls, stock limits, and bans that tank prices and stifle innovation (referring to Essential commodities act). He championed free markets for fair returns and tech adoption, shunning freebies. In this rupee moment, his vision aligns: Currency dynamics amplify market signals he prized, but only if policies dismantle the chokepoints turning opportunities into electoral spats. (See research links below)

What must be done—swiftly and strategically?

Lock in trade stability for 3-5 years. Give exporters and investors—dal millers, oilseed crushers, ethanol units—a clear runway. Abrupt bans and duties deter value-chain bets.

Drive reforms via dialogue. Agriculture lags at ~3.5% growth, a drag on the economy. To vault India to the third-largest by 2030, bold overhauls are non-negotiable—but this time, co-create them with stakeholders to sidestep 2020’s pitfalls.

Revamp CACP’s remit. Mandate the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices to weave in forex risks and import gaps for pulses/oilseeds MSPs—credible, market-tied signals to build trust.

Embrace crop-neutral incentives. Prioritize pulses and oilseeds for their water thrift and nutrition, not just cereals. Gulati’s urgency rings true.

Empower private capacity-building. Price nudges from a weak rupee need muscle: Mills, storage, crushers, cold chains. Slash red tape; expedite land/power nods for agro-processing.

Leverage ethanol smartly. Where plants offset crude imports, promote fitting feedstocks in water-resilient zones—avoiding rice-sugarcane pivots in fragile ecosystems.

Yes, input costs like fertilizers will sting with rupee weakness. But pulses guzzle less fertilizer, and oilseeds demand milder inputs than paddy. Targeted procurement and calibrated aid can buffer shocks, ditching the subsidy spiral.

A sliding rupee pains some, empowers others. Policymakers’ real choice? Harness markets to revitalize farms, or let politics and policy whims fritter away a once-in-a-generation shot. Pairing currency tailwinds with medium-term, credible reforms could forge rural prosperity from apparent frailty. The rupee dips—but Indian agriculture’s ascent has rarely gleamed brighter. Seize it with bold, dialogic resolve. Don’t squander this like 2020.

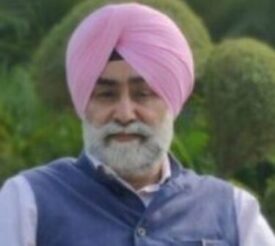

About the author:

Gurpartap Singh Mann is a farmer and former Member of the Punjab Public Service Commission. He has earlier served as Chief General Manager, Punjab Infrastructure Development Board. An Engineer and MBA by qualification, he writes on governance, agriculture, and socio-political issues concerning Punjab.