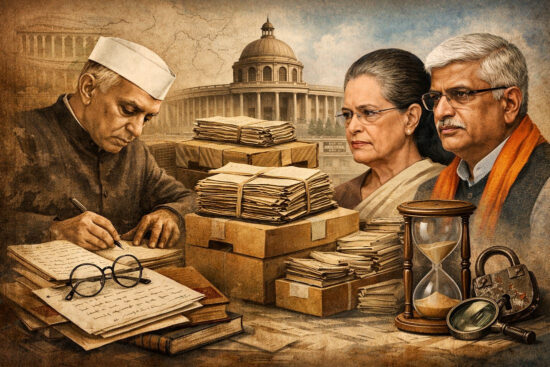

Union Culture Minister Gajendra Singh Shekhawat’s assertion of today (December 28) that he has twice written to Sonia Gandhi asking her to return Jawaharlal Nehru’s papers to the Prime Ministers’ Museum and Library (PMML) is more than a political sally; it goes to the heart of who owns India’s past and on what terms that past can be accessed (video clip). The Nehru papers controversy exposes not merely the anxieties of a ruling party and an Opposition family about narrative and legacy, but a deeper, troubling nebulousness in our legal architecture around documentary heritage and archival justice.

Union Culture Minister Gajendra Singh Shekhawat’s assertion of today (December 28) that he has twice written to Sonia Gandhi asking her to return Jawaharlal Nehru’s papers to the Prime Ministers’ Museum and Library (PMML) is more than a political sally; it goes to the heart of who owns India’s past and on what terms that past can be accessed (video clip). The Nehru papers controversy exposes not merely the anxieties of a ruling party and an Opposition family about narrative and legacy, but a deeper, troubling nebulousness in our legal architecture around documentary heritage and archival justice.

Who Owns Nehru’s Papers?

At stake is a deceptively simple question: can documents created by a man who was first a towering nationalist leader and then India’s first Prime Minister legitimately be treated as “private family papers”, hoarded in private custody, shielded from scholars and citizens alike? Normatively and democratically, the answer ought to be an unambiguous no. These are not the love letters of an obscure private citizen; they are the working and reflective papers of a man who shaped the Indian state, its foreign policy, its institutional architecture and its ideological self-understanding for nearly two decades.

The public record is clear on at least one crucial sequence. In 2008, acting on a request authorised by Sonia Gandhi, around 51 cartons comprising some 26,000 Nehru-related papers were taken out of what was then the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) and handed over to a representative of the Gandhi family. For decades before that, these papers had been housed, catalogued and consulted within a public institution built and maintained at taxpayer expense as a repository of modern India’s documentary memory. The present government now says it has twice requested their return; Gandhi, according to Shekhawat, has “promised cooperation” but has not restored custody.

The category of “private papers” in archival practice does not mean whatever a political dynasty chooses to take home in cardboard boxes. It refers to materials that originate outside the normal course of state business and are deposited in archives by private individuals or organisations, typically by way of gift, deposit or bequest. Even then, once accepted into a public archival institution, they acquire a different character: they become part of the documentary heritage of the nation, and withdrawal is not, and should not be, a casual contractual right exercisable at the pleasure of heirs.

In Nehru’s case, the argument for treating these as more than private is even stronger. Many of the letters and notes in question were created when Nehru was either the head of government or a central figure of the national movement, interacting with freedom fighters, global leaders and officials in ways that deeply intersected with state formation and public policy. The line between his “personal” and “public” roles in those years is so porous as to be almost fictional. It is precisely this entanglement which makes such material of archival importance, not mere family memorabilia.

The Democratic Claim – And the Risk of Physical Loss

A democratic republic cannot credibly claim that its citizens have a right to know their history “good, bad or ugly” while allowing crucial primary material to be effectively sequestered by one family. When key Nehru papers are inaccessible, the injury is not suffered by the BJP or the Congress; it is suffered by research scholars, biographers, students of international relations and constitutional development, and ultimately by the wider public that must rely on partial histories written in the dark. The opacity encourages myth-making on all sides: hagiography flourishes in the absence of inconvenient documents, and demonisation thrives where archival nuance is missing.

There is also a stark practical dimension that is too often ignored in the political crossfire. Modern archives exist not just to store paper but to preserve it to professional and scientific standards over decades and centuries. A private family, however affluent or well-meaning, is rarely equipped to ensure proper security, preservation and conservation in a state-of-the-art manner. National archival institutions openly stress the importance of temperature and humidity control, pest management, acid-free storage and specialist conservation facilities to prevent deterioration. Priceless documents are vulnerable to humidity, termites, silverfish, fungal growth, acidic paper decay, mishandling and simple misplacement when kept in cupboards, trunks and domestic strong-rooms never designed or monitored as controlled archival environments.

By contrast, bodies like the National Archives of India and PMML maintain regulated environmental conditions, pest-control protocols and conservation laboratories, and increasingly back up holdings through digitisation. They create catalogues, finding aids and access policies that allow scholars to know what exists and how it may be consulted. Keeping 51 cartons of Nehru’s papers in private hands is therefore not just a question of access; it is a question of survival. To let them languish unseen in family custody is to gamble, irresponsibly, with a non-renewable part of India’s documentary memory.

A Nebulous Process of Law

Yet, as things stand, the process of law for dealing with such a situation is indeed nebulous. India’s primary statute on documentary heritage, the Public Records Act, 1993, recognises the concept of public records and provides for their management and transfer, but it is strikingly weak when it comes to private custody of historically important papers. It allows the National Archives or Union territory archives to accept records of historical or national importance from private sources “by way of gift, purchase or otherwise” and envisages an Archival Advisory Board that can issue directions for acquisition of records from private custody. But it stops short of articulating a clear, enforceable mechanism for compulsory acquisition of such documents, or for penalising refusal to comply with such directions.

This lacuna matters because it means that in practice, the state’s capacity to recover, in the public interest, critical documentary material wrongfully removed, or withheld, from public repositories is largely dependent on moral suasion and political pressure. When a former ruling family is the custodian, and the papers touch on its own mythology and vulnerabilities, moral suasion is a weak reed. The present stand-off over the Nehru papers is a textbook case of that weakness.

There are, of course, other legal regimes. The Antiquities and Art Treasures Act, 1972, for instance, provides for compulsory acquisition of “antiquities” where the central government believes preservation in a public place is desirable, with a structured compensation mechanism. Its definition of antiquities includes manuscripts and records of historical interest, and one can plausibly argue that mid-20th-century papers of a figure like Nehru fall within its ambit. But that Act has mostly been used in relation to sculptures, paintings and archaeological artefacts rather than modern political papers, and has not yet been tested as a vehicle for seizing contested prime-ministerial correspondence.

The Temptation of a Muscular FIR Route

Against this background, some voices will inevitably suggest a “muscular” path: register an FIR under appropriate sections of the IPC, invoke criminal procedure provisions to search, seize, attach and produce the papers as suspected public property or evidence of an offence. In this vision, the law’s coercive arm would stride in where archival law appears hesitant.

The attractions are obvious, but largely illusory. Once seized, the papers would immediately become case property. Under police and criminal-procedure practice, case property is lodged in the police malkhana and, once produced, kept in court malkhanas or attached record rooms, governed by manuals and rules designed around chain-of-custody and disposal, not conservation. Guidelines on release of seized property and multiple police manuals describe how seized items are registered, stored and then simply lie until disposal orders are passed. Studies and project reports on malkhana management speak candidly of overcrowded, ill-ventilated rooms, shortage of racks, ad hoc packing, rodent and termite infestation and serious risk of loss, pilferage and decay.

Placing irreplaceable, fragile mid-20th-century papers into this ecosystem is close to archival malpractice. The criminal process treats seized items as evidence whose primary function is to support or rebut charges; their custodial regime is built to maintain evidentiary integrity long enough for trial, not to preserve them for a century. Courts regularly authorise destruction, auction or return of case property after trials end; there is no embedded logic that says, “this is documentary heritage and must be conserved forever.” In effect, the FIR-and-seizure route would convert potential archival treasures into vulnerable case property, trapped in the slow mill of criminal procedure, with restricted access and under conditions that could accelerate their deterioration.

A criminal-law approach also sends a damaging signal to other families and estates holding historically important private collections. If the message is that any hesitation or dispute over terms of transfer could invite an FIR and forcible seizure, many will simply retreat further into secrecy, or quietly disperse or sell their holdings to avoid future vulnerability. That would be a net loss for public history.

Archival Eminent Domain and Fair Compensation

India does have better models. The Nizam of Hyderabad’s famed jewellery and art collections were acquired by the Government of India after protracted negotiation and now form part of the holdings displayed in national museums, including at the Salar Jung Museum and elsewhere. Similarly, rare manuscripts, coins and personal collections of notable figures have been purchased by or gifted to the National Archives and other repositories on terms that balance public interest with private rights.

That is the direction in which the Nehru papers dispute ought to move: away from a crude tug-of-war between “family property” and “state property” and towards a principled recognition that certain categories of documentary material have archival importance by definition and must be conserved in public custody, with fair – but not astronomical – compensation if genuinely required. A doctrine of archival eminent domain needs to be articulated in policy and, ideally, legislation: a carefully circumscribed power, exercised sparingly and with due process, to require that historically vital documents be deposited in recognised public archives, whether by transfer of ownership or by deposit with clear access norms.

Such a framework would do three things. First, it would relieve individual families and estates of the invidious power to suppress or selectively release material that bears on the public record. Second, it would offer owners clear assurances that they will be treated fairly, that appraisal and valuation will be professional rather than politically vindictive, and that the sanctity of family privacy – for genuinely intimate material with no wider relevance – will be respected through closure periods or restricted access regimes, as is standard in many archival systems. Third, it would insulate future controversies from the personalised animus that now appears to colour both ministerial statements and Opposition reactions.

A Test for Sonia Gandhi – And for the Government

In the immediate case, the onus lies heavily on Sonia Gandhi and the Congress party. They cannot plausibly claim to stand for transparency, debate and democratic accountability while sitting on cartons of Nehru’s papers that once formed part of the nation’s premier archival holdings. Their decision in 2008 to cart these away from NMML – a decision taken when they were in power, and therefore unchallenged institutionally – now looks, at best, like a serious misjudgment. At worst, it appears as an attempt to reserve to themselves the power to curate Nehru’s memory, deciding which facets of his life and thought are fit for public consumption and which must remain family secrets.

The BJP, for its part, must resist the temptation to treat the matter purely as a stick with which to beat the Gandhi family. If it truly believes, as it says, that these papers belong to the nation and not to a dynasty, it should move towards creating a coherent legal and policy regime that will apply not only to Nehru but to all holders of historically significant private collections, including families ideologically closer to the present government. It should also make a clear, public commitment that once the papers are restored – whether by gift, purchase or legally backed acquisition – they will be properly catalogued, conserved in professional archival conditions and made available to scholars under transparent, non-discriminatory access rules, including eventual digitisation.

In Summary

Ultimately, the Nehru papers debate is not about one leader versus another, or one party’s icon versus another’s. It is about whether India is prepared to take its documentary heritage seriously enough to build a robust, fair and rights