The 2027 Punjab Assembly election has become a case study in how political communication evolves when technology begins to shape not only the message but the messenger. What once required months of ground mobilisation, community meetings, and policy articulation can now be overshadowed by a single well‑timed Instagram reel. The shift is not merely cosmetic; it reflects a deeper transformation in how political legitimacy is constructed and how voters interpret leadership.

The 2027 Punjab Assembly election has become a case study in how political communication evolves when technology begins to shape not only the message but the messenger. What once required months of ground mobilisation, community meetings, and policy articulation can now be overshadowed by a single well‑timed Instagram reel. The shift is not merely cosmetic; it reflects a deeper transformation in how political legitimacy is constructed and how voters interpret leadership.

In earlier decades, a candidate’s credibility emerged from their presence in the constituency — the long hours spent listening to grievances, the slow but steady work of building trust, and the ability to articulate a vision rooted in local realities. Today, that credibility is increasingly mediated through screens. A candidate who once needed to master public speaking now needs to master lighting, framing, and editing. The political stage has not disappeared; it has simply moved into the palm of the voter’s hand.

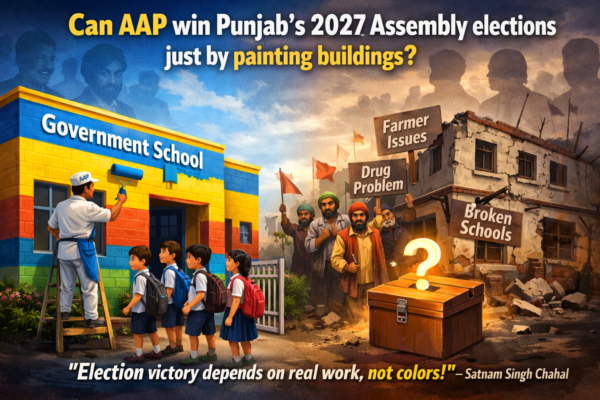

This transition has created a new hierarchy of political skills. The ability to craft a compelling narrative in fifteen seconds often outweighs the ability to explain a policy in fifteen minutes. The pressure to remain constantly visible online forces candidates to prioritize content creation over community engagement. The result is a political culture where visibility becomes a substitute for substance, and where the algorithm becomes an invisible campaign manager.

Yet the consequences extend beyond campaign strategy. When political discourse is compressed into short‑form content, nuance becomes a casualty. Complex issues — unemployment, agriculture, education, public health — are reduced to slogans and aesthetic visuals. The voter is encouraged to react emotionally rather than think critically. The leader becomes a performer, and the public becomes an audience conditioned to applaud rather than question.

But beneath this spectacle lies a contradiction. Punjab’s electorate, especially its youth, is digitally fluent but not digitally naïve. They enjoy the creativity of social media, but they also recognize its limitations. They know that a reel can highlight a problem but cannot fix it. They know that a filter can beautify a moment but cannot beautify governance. This awareness creates a tension between what voters consume online and what they expect offline.

The 2027 election exposes this tension with unusual clarity. Candidates who rely solely on digital charisma risk being exposed when confronted with real‑world expectations. Those who ignore digital platforms risk becoming invisible in a landscape where attention is the most valuable currency. The challenge is not to reject technology but to integrate it without allowing it to replace the fundamentals of leadership.

Ultimately, the rise of Instagram politics is neither a threat nor a triumph. It is a mirror reflecting the society that created it — a society that values speed but still demands sincerity, that enjoys spectacle but still expects service, that embraces innovation but still respects authenticity. The future of Punjab’s political culture will depend on whether leaders can move beyond the chase for virality and return to the slower, more demanding work of earning trust. And it will depend on whether voters can look past the filters and ask the questions that truly matter.