And every year, the result is the same. Farmers blame loot in the mandis; officials deny it; the exploitation continues; and paddy procurement ends with a sour taste. Then comes the visit of a political leader — dressed in a white kurta-pyjama, posing for photographers with a handful of paddy, posting it on Facebook. He publicly warns the Mandi Mafia to behave, then sits in an air-conditioned office for tea and kaju barfi, gets his seva-paani, and leaves. The end.

And every year, the result is the same. Farmers blame loot in the mandis; officials deny it; the exploitation continues; and paddy procurement ends with a sour taste. Then comes the visit of a political leader — dressed in a white kurta-pyjama, posing for photographers with a handful of paddy, posting it on Facebook. He publicly warns the Mandi Mafia to behave, then sits in an air-conditioned office for tea and kaju barfi, gets his seva-paani, and leaves. The end.

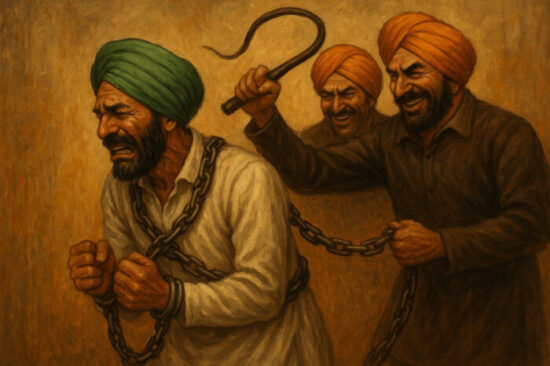

The Mandi Mafia — the cartel of arhtiyas, rice millers, and officials of procurement agencies — feeds on this annual ritual of pain. Yet somehow, the same farmers who are its victims are made to believe that they share a sacred bond with it. “Nau maas da rishta,” they call it — a relationship as intimate as a bond of flesh. Strange indeed.

We have all heard of the Mining Mafia and the Sand Mafia. Believe me, in front of the Mandi Mafia, the Mining Mafia is chillar (small change).

Every harvest, the same drama repeats. Farmers arrive in mandis with faith in the system, but they face a syndicate that has mastered the art of invisible theft. Moisture meters are manipulated, bags are overfilled, grain quality is questioned, and payments are delayed or short-paid. In Fazilka and Muktsar, angry farmers recently alleged that millers and officials were “showing higher moisture” than the actual reading to make extra deductions. Ministers had to rush to the spot; when they checked, they found the farmers were right — the actual moisture was less than what was being recorded.

In Haryana too, the story is no different. The Bhartiya Kisan Union (Charuni) has alleged that procurement agencies and millers are forcing farmers to sell ₹300–₹500 per quintal below MSP, pocketing the difference while showing full MSP payments in official records. The union has even demanded raids and stock-verification of rice mills, calling it a “scam” hiding in plain sight. And when protests broke out in Kurukshetra this month over procurement delays, a senior union leader — who also owns a commission-agent shop in a purchase centre — went so far as to slap a district official. The anger seemed real, but it was a good drama enacted between two covert partners.

Across both states, paddy farmers this season are being underpaid by ₹200–₹500 per quintal below the MSP, even though official ledgers claim full payments. In Punjab alone, losses are estimated at over ₹5,500 crore, with many mandis paying around ₹300 less than the official MSP. For premium aromatic rice, the story is worse. The famed 1121 basmati variety, which fetched ₹5,000 per quintal last year, is being sold this season at just ₹2,900, leaving farmers stunned. In some Haryana mandis, paddy that should have fetched ₹2,389 per quintal under Grade-A MSP has been sold for ₹2,000 per quintal, via kachhi parchis (informal slips).

That is the core of the tragedy. The very system that bleeds the farmer is led, defended, and sometimes personified by those who profit from it. The arhtiyas control credit and inputs; the rice-millers control storage and processing; the officials control paperwork and payments. Together they ensure that the farmer never truly sells freely, never truly earns what the government promises, and never truly escapes the debt cycle.

Former IAS officer K.B.S. Sidhu, in his seminal essay “Stockholm Syndrome in Punjab Mandis,” laid bare this cruel design: a few thousand arhtiyas dominate procurement for more than a million farming families, holding informal debts worth tens of thousands of crores. Farmers, he wrote, have been “kept captive through a mixture of dependence, debt and deception.” They are forced to defend the very network that exploits them because they see no alternative.

👉 Read the essay here.

I have urged him to translate his piece into Punjabi so that farmers can also read this hard truth.

Is former Member of Punjab Public Service Commission

A farmer and keen observer of current affairs

That is why the events of 2020 still sting. When the government introduced the three farm laws — whatever their flaws — they were a step to dismantle the Mandi Mafia, not the Mandi. But the narrative was deliberately twisted to claim that the Mandi system itself was being dismantled. A false fear was spread that private players would replace the state procurement system, when in truth the laws sought to open alternate markets, free the farmer from the clutches of commission agents, and bring overdue reforms pending since 1992.

The syndicate saw the threat early. It poured resources into mobilising farmers against the laws, wrapped the cause in the flag of “Save the Farmer,” and turned genuine grievances into a shield for its own survival.

What made the movement even stronger was political complicity. A major political party in power in Punjab — with long-standing ties to arhtiyas and rice millers — became an active instrument in fanning the agitation. Its leaders, many with deep stakes in the mandi economy, found in the protests both political oxygen and protection for their business interests. What began as an agitation over farm laws was quickly converted into a political counter-movement — one that safeguarded the very ecosystem of exploitation that the reforms had aimed to expose.

Many respected intellectuals, even retired civil servants and journalists, fell for the emotional narrative without grasping who was funding it.

The Great Betrayal

The irony could not be starker. The very arhtiyas who cheat farmers in the mandis stood at the Delhi borders pretending to be their saviours. The same rice millers who inflate moisture readings to cut payments were suddenly called protectors of the MSP. The same agents who trap farmers in debt and charge usurious interest became the faces of a so-called farmers’ movement. And, as the mainstream press itself has reported, some of the most visible leaders of that agitation were arhtiyas by profession — commission agents with their own shops in the mandis. The exploiters led the exploited, and the victims were made to fight for the survival of their oppressors.

When the Harvest Defended the Sickle

In truth, the arhtiyas and rice-millers used the very farmers — the people whose sweat feeds their empire — to fight the battle of the Mandi Mafia. It was as tragic as when the harvest defends the sickle — the very tool that cuts it down. The leaders of the agitation were not shepherds of the poor but traders of the mandis. The farmer bled again, this time not in silence, but in misplaced loyalty — fighting for those who fed on his wounds.

Bonded by Deception

Every year, when procurement begins, the pattern returns — loot in the mandis, delays, deductions, and despair. Every year, the farmer’s complaint is fresh but the culprits are the same. Yet every year, the phrase “nau maas da rishta” is uttered, romanticising a bond that is nothing but financial bondage. The truth is harsh — Punjab’s farmers have become bonded labourers in their own fields, shackled by debt, dependence, and deception. And the most tragic part is that many of them have come to accept this bondage as normal — even to defend it. They have been taught to find comfort in their chains, to see captivity as kinship.

The Mandi Mafia and the Captive Farmer

The farmer’s fight, therefore, is not against reform — it is against capture. But as long as the Mandi Mafia controls the system — aided by political protectors in high office — the farmer will remain a prisoner who mistakes his cage for a home.

Year after year, we will keep seeing the same story.