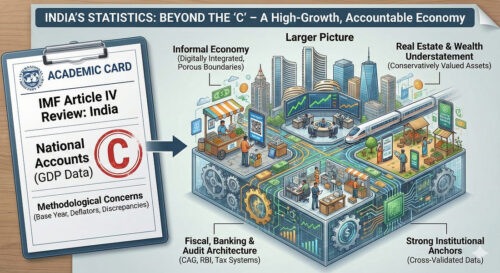

The International Monetary Fund’s latest Article IV review presents a striking contrast. India is described as one of the fastest-growing large economies in the world, yet its national accounts statistics – including GDP and Gross Value Added – have been given a grade of ‘C’, the second-lowest on the Fund’s four-step quality scale. Overall, India’s statistical system is graded ‘B’, but the core of the macro framework is singled out as a weak link.

The International Monetary Fund’s latest Article IV review presents a striking contrast. India is described as one of the fastest-growing large economies in the world, yet its national accounts statistics – including GDP and Gross Value Added – have been given a grade of ‘C’, the second-lowest on the Fund’s four-step quality scale. Overall, India’s statistical system is graded ‘B’, but the core of the macro framework is singled out as a weak link.

A ‘C’ on national accounts is easily interpreted as a suggestion that India’s GDP figures are unreliable or barely adequate. That sits uneasily with the strength and transparency of India’s fiscal, banking and audit architecture, and with the increasingly formal footprint of what is loosely called the informal economy. Some of the IMF’s technical criticisms are valid; the problem is that the overall verdict misses the larger picture.

What the IMF Actually Says

The IMF’s critique is about method, not morality. It does not claim that India fabricates numbers. Its concerns centre on an outdated base year of 2011–12 for GDP and the Consumer Price Index; continued reliance on wholesale price indices as deflators in the absence of a producer price index; discrepancies between GDP measured by the production or income approach and GDP measured by the expenditure approach; and limited use of seasonal adjustment and more sophisticated techniques in quarterly national accounts. On inflation, India receives a ‘B’, but here too the Fund worries that the CPI basket and weights no longer reflect changed consumption patterns.

Taken on their own, these points amount to a call for modernisation rather than a charge of bad faith. Yet grading national accounts a ‘C’ suggests a level of weakness that, in India’s case, is not borne out by the institutional foundations of its statistics.

A Statistical and Audit Framework with Teeth

India’s public finance and accounting systems are not those of a low-capacity, opaque state. At their heart lies the Comptroller and Auditor General, an independent constitutional authority mandated to audit all receipts and expenditure of the Union and the States. The CAG’s reports are laid before Parliament and state legislatures and examined by Public Accounts Committees and other committees drawn from across the political spectrum.

Government borrowing is conducted through the Reserve Bank of India within explicit limits and reporting norms. Budget documents, RBI publications and CAG reports cross-validate one another. Direct and indirect tax collections are tracked through administrative systems and reconciled with treasury accounts. Corporate accounts are subject to statutory audit and, where listed, to securities regulation. In such a framework, the scope for systematically fudging fiscal and financial data by meaningful magnitudes is extremely limited. National accounts, however imperfect, are built on top of this backbone.

India’s Informal Economy: Porous, Not Fuzzy

Much unease about Indian data arises from a stylised picture of the informal sector as a statistical black hole, sitting outside the formal system and beyond measurement. That picture is misleading. The informal economy is better seen as a set of activities that are only partially formalised.

Take a street vendor. He may not be registered for GST or file returns in his own name, but the goods he sells have almost certainly borne GST at earlier stages of the supply chain. The wholesaler or distributor from whom he buys will be reporting those transactions to the tax authorities. When the vendor uses digital payments for some sales, maintains a bank account opened under a financial inclusion scheme, or services a small loan for his cart or scooter, further pieces of his economic life show up in banking, credit and utility datasets.

Unreported income is therefore not the same thing as unmeasured activity. Funds that escape direct taxation are still spent, saved and invested through channels that leave a footprint: purchases of goods and services, bank deposits, school fees and electricity bills, financial assets and housing. Each of these flows enters formal databases in some form. The boundary between formal and informal is porous rather than watertight. The informal sector poses challenges of modelling and attribution, but it is not a formless fuzz that invalidates macro aggregates. It is also an economic strength, providing flexibility, self-employment and micro-entrepreneurship that help the economy absorb shocks and reallocate labour.

Banking, Taxation and the Understatement of Wealth

The credibility of India’s macro data ultimately rests on the discipline imposed by financial and tax accounting. Bank deposits, housing loans and other credit are recorded with precision by regulated institutions and monitored by the central bank. Tax authorities maintain detailed records of direct and indirect tax receipts; GST collections, income tax payments and customs duties are reported and reconciled. Corporate financial statements are scrutinised by auditors and regulators. These interlocking systems impose a hard constraint on how far macro aggregates can drift from reality.

In many ways, India’s official statistics are more likely to understate than overstate private wealth. Real estate is a clear example. In most states, circle rates or guideline values used for registering property are significantly below market prices. Transactions often comprise a declared component at or near the circle rate and an additional component that may not be fully reported. The recorded value of the housing stock, and of the related tax base, is therefore conservative. Where homes are financed by formal mortgages, the loan values are precisely recorded even if the underlying property is worth more than its registered value. The national balance sheet, taken at face value, is almost certainly a lower bound on the assets actually held by Indian households.

Modernising Methods Without Undermining Confidence

None of this is to suggest that India’s statistical system is beyond reproach. Base years for GDP and CPI do need to be updated; producer price indices must be expanded; and the coverage of enterprise and household surveys can be improved. Better seasonal adjustment and richer disaggregation of quarterly data would help policymakers and analysts.

The IMF is well within its mandate to press India to move faster on such modernisation. Where its assessment becomes problematic is in the jump from specific methodological criticisms to a sweeping ‘C’ on national accounts. That grade implies a degree of unreliability that does not sit well with a country whose fiscal numbers are audited and debated to the last rupee, whose banking and tax systems are dense with data, and whose so-called informal economy is deeply enmeshed with formal circuits of money and information.

A more balanced reading would acknowledge that India’s statistics while not perfect and evolving, but fundamentally anchored in accountable institutions and verifiable financial flows. To miss that anchoring is to miss the larger picture. In grading India’s data, the IMF should recognise not only the gaps in method but also the strengths of a system in which economic reality ultimately has to add up.

Punjab’s Economic Condition (2022–2025): A Detailed Analysis

Between 2022 and 2025, Punjab’s economy moved through a period of cautious recovery mixed with deep structural stress. On the one hand, the state’s Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) expanded steadily in nominal terms, pushing per-capita income upward year after year. On the other hand, Punjab’s fiscal foundations continued to weaken under the weight of high deficits, rising debt, and large annual repayment obligations. This combination created a situation where the size of the economy was growing, yet the state’s ability to invest in development remained restricted. Understanding this period requires looking not only at headline numbers but at agriculture, industry, revenue patterns, and long-term vulnerabilities.

Punjab’s nominal GSDP increased each year from 2022 to 2025, recovering from the slowdown that followed the pandemic. Budget estimates projected that, by 2024–25, the size of Punjab’s economy would cross ₹8 lakh crore in nominal terms. This growth helped raise the state’s per-capita income, which climbed from about ₹1.8–1.9 lakh in 2021–22 to nearly ₹1.95 lakh in 2023–24, with further increases estimated for 2024–25. These numbers place Punjab above many Indian states in terms of average income, reflecting a historically strong economic base. However, the rise in per-capita income was largely nominal, partly driven by inflation, and did not always translate into proportional increases in real purchasing power for ordinary families.

While GSDP and income figures show progress, Punjab’s fiscal health during this period deteriorated. The state consistently recorded high fiscal deficits—around 5 percent of GSDP in 2022–23 and 2023–24—which meant that year after year, Punjab borrowed heavily to meet its expenditure needs. A significant share of these borrowings did not fund new development projects but were instead consumed by repayments of old debt. In 2024–25 alone, the government allocated nearly ₹70,000 crore purely for debt repayment, a figure that illustrates how past liabilities have grown into a major burden on present finances. As a result, debt servicing has increasingly eaten into the state budget, leaving less room for capital spending on roads, health facilities, education infrastructure, industry support, or agricultural modernization.

The mismatch between Punjab’s revenue generation and expenditure commitments lies at the heart of this fiscal pressure. While the state collects taxes through GST, excise, stamp duty, and other sources, its revenue base has not grown fast enough to match its spending obligations. Large portions of the budget go towards salaries, pensions, subsidies, and interest payments—expenditures that are difficult to reduce due to administrative, social, and political constraints. Even though the government attempted reforms and stricter financial discipline, the structural imbalance between income and expenditure continued, pushing public debt upwards each year. This situation increased rollover risk, meaning Punjab constantly needed new loans to pay off old ones.

Sector-wise, Punjab’s economic structure during 2022–2025 continued to show both strengths and weaknesses. Agriculture remained the backbone of the state, supporting a large proportion of the population. Yet, reliance on the wheat-rice cropping cycle, groundwater depletion, low diversification, and rising input costs limited income growth for farmers. Industrial growth was mixed: cities like Ludhiana, Jalandhar, Mohali, and Bathinda retained strong SME clusters, but many small industries struggled with credit access, outdated technology, and competition from other states. The services sector expanded steadily—especially in education, transport, retail, and healthcare—helping drive overall GSDP growth, though not always generating high-quality jobs for the youth.

The employment picture during these years reflected these structural challenges. Official unemployment rates varied by survey, but under-employment, especially among rural youth, remained high. Job creation did not keep pace with the aspirations of Punjab’s educated young population, contributing to increasing migration abroad. Although Punjab’s social indicators such as literacy, life expectancy, and access to basic services remain better than many states, rising private education and healthcare costs, coupled with limited job opportunities, put pressure on household finances. Thus, even as per-capita income rose in nominal terms, many families continued to feel economic stress.

By 2025, a clear pattern had emerged: Punjab’s economy had size and potential but was constrained by debt, deficits, and structural imbalances. High debt servicing costs meant that the government could not invest adequately in growth-enhancing sectors like agro-processing, manufacturing modernization, skill development, and infrastructure. Agriculture required a decisive shift toward diversification, but the pace of reform remained slow. Industry required stronger policy support, easier credit, and better logistics. Meanwhile, the state needed a broader revenue base and cleaner fiscal strategies to break the cycle of borrowing for repayment.

Looking ahead, Punjab’s path to sustainable economic health will depend on improving revenue collections, bringing deficits under control, and focusing public spending on long-term productivity rather than short-term obligations. A planned shift towards high-value agriculture, new industrial clusters, and a stronger service economy could restore dynamism. Equally important will be debt management, transparent financial planning, and targeted support to sectors that create stable employment. Without these shifts, Punjab risks carrying its growing debt burden into the future, limiting its ability to provide opportunities to its people.

If you want, I can also prepare:

(a) A press-release version

(b) A Punjabi version

(c) A longer multi-page report with headings and data tables.

ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦੀ ਆਰਥਿਕ ਸਥਿਤੀ (2022–2025): ਇੱਕ ਵਿਆਪਕ ਅਤੇ ਗਹਿਰਾ ਵਿਸ਼ਲੇਸ਼ਣ

2022 ਤੋਂ 2025 ਤੱਕ ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦੀ ਆਰਥਿਕਤਾ ਇੱਕ ਕਟਿਨ ਦੌਰ ਵਿਚੋਂ ਗੁਜਰੀ। ਇੱਕ ਪਾਸੇ ਰਾਜ ਦਾ ਗ੍ਰੋਸ ਸਟੇਟ ਡੋਮੈਸਟਿਕ ਪ੍ਰੋਡਕਟ (GSDP) ਕਾਗਜ਼ੀ ਅੰਕਾਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਲਗਾਤਾਰ ਵਧਦਾ ਰਿਹਾ ਅਤੇ ਪ੍ਰਤੀ ਵਿਅਕਤੀ ਆਮਦਨੀ ਵੀ ਸਾਲਾਨਾ ਵਧੀ। ਦੂਜੇ ਪਾਸੇ, ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦੀ ਵਿੱਤੀ ਨੀਂਹ ਕਮਜ਼ੋਰ ਹੁੰਦੀ ਗਈ ਕਿਉਂਕਿ ਰਾਜ ਨੂੰ ਹਰ ਸਾਲ ਵੱਡੇ ਘਾਟੇ, ਬਹੁਤ ਜ਼ਿਆਦਾ ਕਰਜ਼ੇ ਅਤੇ ਪੁਰਾਣੇ ਕਰਜ਼ਿਆਂ ਦੀ ਮੋਟੀ ਕਿਸ਼ਤਾਂ ਨੇ ਜਕਡਿਆ ਰੱਖਿਆ। ਇਸ ਸਮੇਂਕਾਲ ਵਿੱਚ ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦਾ ਆਰਥਿਕ ਆਕਾਰ ਤਾਂ ਵਧਿਆ, ਪਰ ਕਰਜ਼ਿਆਂ ਅਤੇ ਘਾਟੇ ਕਾਰਨ ਸਰਕਾਰ ਕੋਲ ਵਿਕਾਸ ਲਈ ਖਰਚ ਕਰਨ ਦੀ ਸਮਰੱਥਾ ਘੱਟਦੀ ਗਈ। ਇਸ ਦੌਰ ਨੂੰ ਸਮਝਣ ਲਈ ਸਿਰਫ਼ ਅੰਕੜੇ ਨਹੀਂ, ਸਗੋਂ ਖੇਤੀਬਾੜੀ, ਉਦਯੋਗ, ਰਾਜਸਵ, ਕਰਜ਼ਾ ਪ੍ਰਬੰਧਨ ਅਤੇ ਰੋਜ਼ਗਾਰ ਦੇ ਰੁਝਾਨਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਵੀ ਸਮਝਣਾ ਜ਼ਰੂਰੀ ਹੈ।

ਸਭ ਤੋਂ ਪਹਿਲਾਂ ਵਧਦੇ GSDP ਅਤੇ ਪ੍ਰਤੀ ਵਿਅਕਤੀ ਆਮਦਨੀ ਦੀ ਗੱਲ ਕਰੀਏ। ਕੋਵਿਡ ਤੋਂ ਬਾਅਦ ਦੀ ਮੰਦਾਵਟ ਤੋਂ ਬਾਹਰ ਨਿਕਲਦੇ ਹੋਏ 2022 ਤੋਂ 2025 ਦੀ ਮਿਆਦ ਵਿੱਚ ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦੀ ਅਰਥਵਿਵਸਥਾ ਨੇ ਕਾਗਜ਼ੀ ਰੂਪ ਵਿੱਚ ਮਜ਼ਬੂਤ ਵਾਧਾ ਦਰਜ ਕੀਤਾ। ਰਾਜ ਦਾ ਨਾਮਾਤਰ GSDP 2024–25 ਤੱਕ ਲਗਭਗ 8 ਲੱਖ ਕਰੋੜ ਰੁਪਏ ਦੇ ਪੱਧਰ ਨੂੰ ਛੂਹ ਗਿਆ। ਇਸ ਨਾਲ ਪ੍ਰਤੀ ਵਿਅਕਤੀ ਆਮਦਨੀ ਵੀ ਵਧੀ ਜੋ 2021–22 ਵਿੱਚ 1.8–1.9 ਲੱਖ ਦੇ ਆਲੇ-ਦੁਆਲੇ ਸੀ, ਅਤੇ 2023–24 ਵਿੱਚ 1.95 ਲੱਖ ਰੁਪਏ ਤੱਕ ਪਹੁੰਚ ਗਈ, ਜਦਕਿ 2024–25 ਲਈ ਇਸ ਤੋਂ ਵੱਧ ਅੰਦਾਜ਼ੇ ਜਤਾਏ ਗਏ। ਇਹ ਅੰਕੜੇ ਦੱਸਦੇ ਹਨ ਕਿ ਪੰਜਾਬ ਹਾਲੇ ਵੀ ਕਈ ਭਾਰਤੀ ਰਾਜਾਂ ਨਾਲੋਂ ਪ੍ਰਤੀ ਵਿਅਕਤੀ ਆਮਦਨੀ ਦੇ ਮਾਮਲੇ ਵਿੱਚ ਅੱਗੇ ਹੈ। ਪਰ ਇਹ ਵਾਧਾ ਵੱਡੇ ਹੱਦ ਤੱਕ ਸਿਰਫ਼ ਨਾਮਾਤਰ ਸੀ—ਮਹਿੰਗਾਈ ਅਤੇ ਰੁਪਏ ਦੀ ਕੀਮਤ ਵਿੱਚ ਕਮੀ ਨੇ ਇਹ ਤਸਵੀਰ ਹਕੀਕਤ ਵਿੱਚ ਕਮਜ਼ੋਰ ਕਰ ਦਿੱਤੀ, ਕਿਉਂਕਿ ਲੋਕਾਂ ਦੀ ਹਕੀਕਤੀ ਖਰੀਦ ਸਮਰੱਥਾ ਇਸਦੀ ਗਤੀ ਨਾਲ ਨਹੀਂ ਵਧੀ।

ਫਾਇਨੈਂਸ ਦੇ ਮੋਰਚੇ ’ਤੇ ਸਥਿਤੀ ਕਾਫ਼ੀ ਖਤਰਨਾਕ ਹੋਈ। 2022–23 ਤੋਂ 2024–25 ਤੱਕ ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦਾ ਵਿੱਤੀ ਘਾਟਾ GSDP ਦਾ ਲਗਭਗ 5 ਪ੍ਰਤੀਸ਼ਤ ਰਿਹਾ, ਜੋ ਕਿ ਇੱਕ ਬਹੁਤ ਉੱਚਾ ਦਰਜਾ ਹੈ। ਇਸਦਾ ਸਿੱਧਾ ਅਰਥ ਸੀ ਕਿ ਸੰਭਾਵੀ ਵਿਕਾਸ ਲਈ ਨਹੀਂ, ਸਗੋਂ ਰੋਜ਼ਮਰਾ ਦੇ ਖਰਚੇ ਅਤੇ ਪੁਰਾਣੇ ਕਰਜ਼ਿਆਂ ਦੀਆਂ ਕਿਸ਼ਤਾਂ ਭਰਨ ਲਈ ਸਰਕਾਰ ਨੂੰ ਮੁੜ-ਮੁੜ ਕਰਜ਼ੇ ਚੁੱਕਣੇ ਪਏ। 2024–25 ਦੇ ਬਜਟ ਵਿੱਚ ਕੇਵਲ ਕਰਜ਼ਿਆਂ ਦੀਆਂ ਪੁਰਾਣੀਆਂ ਕਿਸ਼ਤਾਂ ਚੁਕਾਉਣ ਲਈ ਹੀ ਲਗਭਗ 70,000 ਕਰੋੜ ਰੁਪਏ ਰੱਖੇ ਗਏ। ਇਹ ਅੰਕੜਾ ਦੱਸਦਾ ਹੈ ਕਿ ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦੀ ਵਿੱਤੀ ਹਾਲਤ ਵਿੱਚ ਸਭ ਤੋਂ ਵੱਡਾ ਬੋਝ ਕਰਜ਼ੇ ਹਨ, ਅਤੇ ਇਹ ਬੋਝ ਹਰ ਸਾਲ ਹੋਰ ਵੀ ਵਧ ਰਿਹਾ ਹੈ। ਕਰਜ਼ਿਆਂ ਦੀ ਇਹ ਲਗਾਤਾਰ ਚੁਕਵਾਈ ਰਾਜ ਦੇ ਵਿਕਾਸ ਖਰਚੇ—ਜਿਵੇਂ ਨਵੇਂ ਸਕੂਲ, ਹਸਪਤਾਲ, ਸੜਕਾਂ, ਉਦਯੋਗਿਕ ਬੁਨਿਆਦਾਂ ਅਤੇ ਖੇਤੀਬਾੜੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਨਿਵੇਸ਼—ਉੱਤੇ ਨਕਾਰਾਤਮਕ ਪ੍ਰਭਾਵ ਪਾਉਂਦੀ ਹੈ।

ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦੇ ਆਮਦਨੀ ਸਰੋਤ ਇਸ ਮਿਆਦ ਵਿੱਚ ਖਾਸ ਨਹੀਂ ਵਧੇ। GST, ਐਕਸਾਈਜ਼, ਸਟੈਂਪ ਡਿਊਟੀ ਅਤੇ ਹੋਰ ਸਰੋਤਾਂ ਤੋਂ ਆਉਣ ਵਾਲਾ ਟੈਕਸ ਰਿਵੈਨਿਊ ਵਧਿਆ ਤਾਂ ਹੈ, ਪਰ ਉਹ ਰਾਜ ਦੇ ਭਾਰੀ-ਭਰਕਮ ਖਰਚ ਨੂੰ ਪੂਰਾ ਕਰਨ ਲਈ ਕਾਫ਼ੀ ਨਹੀਂ ਸੀ। ਤਨਖਾਹਾਂ, ਪੈਨਸ਼ਨਾਂ, ਸਬਸਿਡੀਆਂ ਅਤੇ ਬਿਆਜ ਦੇ ਭੁਗਤਾਨਾਂ ਨੇ ਕਈ ਵਾਰ ਕੁੱਲ ਖਰਚੇ ਦਾ ਵੱਡਾ ਹਿੱਸਾ ਖਾ ਲਿਆ। ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦੀ ਸਰਕਾਰੀ ਆਰਥਿਕਤਾ ਵਿੱਚ ਇਹ ਉਹ ਖੇਤਰ ਹਨ ਜਿਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਕਟੌਤੀ ਕਰਨਾ ਰਾਜਨੀਤਿਕ ਅਤੇ ਪ੍ਰਸ਼ਾਸਕੀ ਤੌਰ ’ਤੇ ਕਾਫੀ ਮੁਸ਼ਕਲ ਮੰਨਿਆ ਜਾਂਦਾ ਹੈ। ਇਸ ਕਾਰਨ ਸਰਕਾਰ ਦੇ ਕੋਲ ਵਿਕਾਸ ਲਈ ਖਰਚ ਕਰਨ ਦੀ ਗੁੰਜਾਇਸ਼ ਘੱਟਦੀ ਗਈ ਅਤੇ ਕਰਜ਼ਿਆਂ ’ਤੇ ਨਿਰਭਰਤਾ ਵਧਦੀ ਗਈ।

ਸੈਕਟਰਾਂ ਦੀ ਗੱਲ ਕਰੀਏ ਤਾਂ ਖੇਤੀਬਾੜੀ ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦੀ ਰਿੜਕ ਹੱਡੀ ਰਹੀ, ਪਰ 2022–2025 ਦੌਰਾਨ ਇਸ ਖੇਤਰ ਨੇ ਕਈ ਚੁਣੌਤੀਆਂ ਦਾ ਸਾਹਮਣਾ ਕੀਤਾ। ਗਹਿਰੇ ਟਿਊਬਵੈਲਾਂ ਕਾਰਨ ਪਾਣੀ ਦੀ ਕਮੀ, ਰੁੜਕੀ ਹੋਈ ਗੈਂਹੂ-ਚਾਵਲ ਚੱਕਰੀ, ਲਗਾਤਾਰ ਵਧਦੇ ਖਰਚੇ ਅਤੇ ਵਧੀਆ ਕੀਮਤਾਂ ਦੀ ਘਾਟ ਨੇ ਕਿਸਾਨੀ ਦੀ ਆਮਦਨੀ ਨੂੰ ਰੋਕਿਆ ਰੱਖਿਆ। ਉਦਯੋਗਿਕ ਖੇਤਰ ‘ਚ ਲੁਧਿਆਣਾ, ਜਲੰਧਰ, ਮੋਹਾਲੀ ਅਤੇ ਬਠਿੰਡਾ ਵਰਗੇ ਹੱਬਾਂ ਨੇ ਆਪਣੀ ਤਾਕਤ ਬਰਕਰਾਰ ਰੱਖੀ, ਪਰ ਛੋਟੇ ਅਤੇ ਮੱਧਮ ਉਦਯੋਗਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਬੈਂਕ ਕ੍ਰੈਡਿਟ, ਤਕਨੀਕ ਤੇ ਬਾਜ਼ਾਰ ਮੁਕਾਬਲੇ ਦੀਆਂ ਕਈ ਰੁਕਾਵਟਾਂ ਦਾ ਸਾਹਮਣਾ ਕਰਨਾ ਪਿਆ। ਇਸਦੇ ਮੁਕਾਬਲੇ ਸਰਵਿਸ ਸੈਕਟਰ—ਜਿਵੇਂ ਰਿਟੇਲ, ਟਰਾਂਸਪੋਰਟ, ਸਿੱਖਿਆ ਅਤੇ ਹੇਲਥਕੇਅਰ—ਵਧੀਆ ਰਫ਼ਤਾਰ ਨਾਲ ਵਧਦਾ ਰਿਹਾ ਅਤੇ ਰਾਜ ਦੇ GSDP ਵਿੱਚ ਜ਼ਿਆਦਾ ਹਿੱਸੇਦਾਰੀ ਬਣਾਉਂਦਾ ਗਿਆ। ਹਾਲਾਂਕਿ ਇੱਥੇ ਬਣਦੀਆਂ ਨੌਕਰੀਆਂ ਹਮੇਸ਼ਾ ਉੱਚ ਗੁਣਵੱਤਾ ਜਾਂ ਲੰਬੇ ਸਮੇਂ ਦੀ ਸਥਿਰ ਆਮਦਨੀ ਵਾਲੀਆਂ ਨਹੀਂ ਰਹੀਆਂ।

ਰੋਜ਼ਗਾਰ ਦੇ ਮੋਰਚੇ ’ਤੇ ਵੀ ਸਥਿਤੀ ਚਿੰਤਾਜਨਕ ਰਹੀ। ਸਰਕਾਰੀ ਅੰਕੜੇ ਅਤੇ ਸਰਵੇਅ ਇੱਕੋ ਜਿਹੀ ਤਸਵੀਰ ਨਹੀਂ ਦਿਖਾਉਂਦੇ, ਪਰ ਇੱਕ ਗੱਲ ਸਪੱਸ਼ਟ ਹੈ ਕਿ ਵਿੱਤੀ ਜਾਂ ਆਰਥਿਕ ਵਾਧੇ ਦੀ ਗਤੀ ਦੇ ਮੁਕਾਬਲੇ ਨੌਕਰੀਆਂ ਦੀ ਸਿਰਜਣਾ ਕਾਫੀ ਹੌਲੀ ਰਹੀ। ਪੜ੍ਹੇ-ਲਿਖੇ ਯੁਵਾ ਵਿੱਚ ਬੇਰੁਜ਼ਗਾਰੀ ਅਤੇ ਅਧ-ਰੋਜ਼ਗਾਰੀ ਵਧਦੀ ਗਈ ਅਤੇ ਇਸ ਕਾਰਨ ਰਾਜ ਤੋਂ ਬਾਹਰ, ਖ਼ਾਸਕਰ ਵਿਦੇਸ਼ਾਂ ਵੱਲ, ਮਾਈਗ੍ਰੇਸ਼ਨ ਰੁਝਾਨ ਹੋਰ ਮਜ਼ਬੂਤ ਹੋਏ। ਹਾਲਾਂਕਿ ਮਨੁੱਖੀ ਵਿਕਾਸ ਦੇ ਕਈ ਸੂਚਕਾਂ ‘ਤੇ ਪੰਜਾਬ ਅਜੇ ਵੀ ਭਾਰਤ ਦੇ ਬਿਹਤਰ ਰਾਜਾਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਰਹਿੰਦਾ ਹੈ, ਪਰ ਵਧ ਰਹੀਆਂ ਨਿੱਜੀ ਸਿੱਖਿਆ/ਹੇਲਥਕੇਅਰ ਲਾਗਤਾਂ ਅਤੇ ਰੋਜ਼ਗਾਰ ਦੀ ਘਾਟ ਨੇ ਘਰੇਲੂ ਆਰਥਿਕ ਦਬਾਅ ਵਧਾਇਆ।

2025 ਤੱਕ ਇੱਕ ਸਪੱਸ਼ਟ ਤਸਵੀਰ ਬਣ ਗਈ ਸੀ: ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦੀ ਆਰਥਿਕਤਾ ਦਾ ਆਕਾਰ ਤਾਂ ਵਧ ਰਿਹਾ ਹੈ, ਪਰ ਕਰਜ਼ੇ, ਘਾਟੇ ਅਤੇ ਸਾਢੇਪਣ ਕਾਰਨ ਵਿਕਾਸ ਦੀ ਸੰਭਾਵਨਾ ਸੀਮਤ ਹੋ ਰਹੀ ਹੈ। ਲਗਾਤਾਰ ਕਰਜ਼ੇ ਚੁਕਾਉਣ ਦੀ ਮਜ਼ਬੂਰੀ ਨੇ ਸਰਕਾਰ ਦੀ ਵਿਕਾਸ ਯੋਜਨਾਬੰਦੀ ਨੂੰ ਰੋਕ ਦਿੱਤਾ ਹੈ। ਖੇਤੀਬਾੜੀ ਨੂੰ ਤੁਰੰਤ ਅਤੇ ਹਿੰਮਤੀ ਫ਼ਸਲੀ ਵਿਭਿੰਨਤਾ ਦੀ ਲੋੜ ਹੈ। ਉਦਯੋਗ ਨੂੰ ਤਕਨੀਕੀ ਅੱਪਗ੍ਰੇਡੇਸ਼ਨ, ਸਸਤੀ ਉਰਜਾ, ਲਾਜਿਸਟਿਕਸ ਅਤੇ ਆਸਾਨ ਕ੍ਰੈਡਿਟ ਦੀ ਲੋੜ ਹੈ। ਸਰਵਿਸ ਸੈਕਟਰ ਨੂੰ ਨੌਜਵਾਨਾਂ ਲਈ ਵੱਡੇ ਪੱਧਰ ’ਤੇ ਸਕਿਲ ਡਿਵੈਲਪਮੈਂਟ ਦੀ ਜ਼ਰੂਰਤ ਹੈ। ਇਸਦੇ ਨਾਲ ਸਰਕਾਰ ਨੂੰ ਆਪਣਾ ਰਾਜਸਵ ਆਧਾਰ ਵਧਾਉਣ, ਖਰਚੇ ਦਰੁਸਤ ਕਰਨ ਅਤੇ ਕਰਜ਼ਾ ਪ੍ਰਬੰਧਨ ਦੀ ਲੰਬੀ ਰਣਨੀਤੀ ਲਾਗੂ ਕਰਨ ਦੀ ਲੋੜ ਹੈ।

ਜੇ ਇਹ ਸੁਧਾਰ ਨਹੀਂ ਕੀਤੇ ਜਾਂਦੇ ਤਾਂ ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦਾ ਕਰਜ਼ਾ ਬੋਝ ਆਉਣ ਵਾਲੇ ਸਾਲਾਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਹੋਰ ਵੀ ਭਾਰੀ ਹੋ ਸਕਦਾ ਹੈ, ਅਤੇ ਰਾਜ ਦੀ ਸਮਰੱਥਾ—ਚਾਹੇ ਵਿਕਾਸ ਕਾਰਜਾਂ ਲਈ ਹੋਵੇ ਜਾਂ ਲੋਕਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਮੌਕੇ ਦੇਣ ਲਈ—ਸੀਮਿਤ ਰਹਿ ਜਾਵੇਗੀ। ਪਰ ਜੇ ਰਾਜ ਫਾਇਨੈਂਸ ਵਿੱਚ ਪਾਰਦਰਸ਼ਤਾ, ਖੇਤੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਨਵੀਂ ਦਿਸ਼ਾ, ਉਦਯੋਗ ਲਈ ਨਵੇਂ ਕਲਸਟਰ ਅਤੇ ਰੋਜ਼ਗਾਰ ਸਿਰਜਣ ਨੂੰ ਕੇਂਦਰ ਬਣਾਉਂਦਾ ਹੈ, ਤਾਂ ਪੰਜਾਬ ਇੱਕ ਵਾਰ ਫਿਰ ਮਜ਼ਬੂਤ ਆਰਥਿਕਤਾ ਵੱਲ ਵਾਪਸ ਜਾ ਸਕਦਾ ਹੈ।