“Development” is one of those words that sounds self-evident until you ask a roomful of citizens to define it. Then certainty dissolves into a bundle of shifting priorities—changing with time, scarcity, technology, demography, and the anxieties of the day. In the early decades after Independence, development was not a slogan; it was survival. Feeding a teeming population, stabilising prices, building irrigation, and raising foodgrain output were not ideological choices but civilisational imperatives.

“Development” is one of those words that sounds self-evident until you ask a roomful of citizens to define it. Then certainty dissolves into a bundle of shifting priorities—changing with time, scarcity, technology, demography, and the anxieties of the day. In the early decades after Independence, development was not a slogan; it was survival. Feeding a teeming population, stabilising prices, building irrigation, and raising foodgrain output were not ideological choices but civilisational imperatives.

Then the priorities evolved—as they had to. Public health moved to the centre: immunisation, drinking water, sanitation, maternal care, and infant mortality. Education rose in successive waves—enrolment first, adult literacy later, and then the harder questions of learning outcomes, employable skills, and social mobility. Infrastructure followed its own rhythm: village electrification, rural roads, connectivity, and the long journey from isolation to access. Poverty alleviation came to dominate political language for decades, often expressed through a constantly changing menagerie of schemes: renamed, re-badged, and re-announced, yet rarely replaced by a simpler, measurable contract with the citizen.

That long arc teaches a simple truth: there has never been a universally accepted definition of development because the country’s needs have never stood still. Development is indeed a concept, and it is certainly a process. But it becomes something else entirely when it is reduced to rhetoric—designed to keep people beguiled by a horizon that keeps retreating.

The slogan problem: when the future becomes an escape route

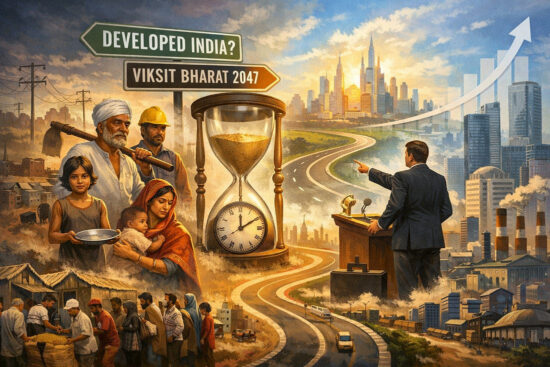

Contemporary political vocabulary is crowded with big words and bigger timelines: Vikas, Atmanirbhar Bharat, “Developed India”, “world’s third-largest economy”, and the grand banner of Viksit Bharat 2047. A national vision is not illegitimate. Every serious state needs direction. But the democratic problem begins when “direction” becomes a substitute for accountability.

A government is elected for five years. Its authority—moral, legal, and constitutional—derives from that limited mandate. It does not have the right to demand that citizens suspend judgement for two or three decades while it paints an alluring mural of the future. Voters do not elect philosophers of civilisation; they elect administrators of the present.

Here the old warning attributed to Keynes lands with particular force: “In the long run, we are all dead.” Long-run promises are politically convenient precisely because they postpone the moment of truth. If development is always twenty years away, it becomes unfalsifiable—and therefore unpunishable. The horizon can be endlessly extended, and the citizen is invited to admire the ambition rather than audit the delivery.

Development cannot be GDP alone—and India itself proves it

Politicians love a single number that can be chanted from stages and printed on billboards. GDP serves that purpose. It matters—no sensible person denies that a growing economy enlarges the possibilities of public policy. But development is the lived experience of growth, not the press release about it.

That is why the world does not define development solely by output. A more credible lens combines income with health and education—because a society that is richer on paper but sick, poorly educated, and insecure in everyday life cannot plausibly call itself developed.

Now consider the most uncomfortable juxtaposition in contemporary India: triumphant talk of a multi-trillion-dollar economy alongside the persistence of mass food support. When a state provides food security at scale, it deserves credit for preventing hunger and distress. But it cannot simultaneously pretend that the presence of such a vast safety net is irrelevant to the meaning of development. A nation does not become developed simply because its GDP is large; it becomes developed when ordinary citizens do not require extraordinary lifelines to secure basic nutrition.

This is why the question is not merely rhetorical: what is the value of a gigantic economy—celebrated for size and rank—if the state must still carry a massive population on free foodgrains? The issue is not whether welfare is “good” or “bad”. The issue is what welfare at that scale reveals about the distance between aggregate wealth and household security.

Equity is not an “add-on”; it is the definition

If development has any moral centre, it is equity: who gets what, how fairly, and with what dignity. Growing the pie is essential, but the purpose of the state is not to turn national output into a museum piece—admired by investors while the median citizen struggles to purchase the basics.

When wealth and income concentrate too strongly, democracy begins to resemble a tournament of patronage. The citizen’s relationship with the state changes—from rights to favours, from entitlements to “connections”. Then “development” becomes a word people hear but do not feel. In such a setting, the argument that India is becoming a “large economy” can coexist—quite comfortably—with the experience of persistent precarity for those who are not positioned to benefit from new opportunities.

Equity is not merely a moral statement; it is an institutional design question. It involves wages, jobs, access to quality public services, and—inevitably—taxation.

The taxation paradox: who carries the state?

Tax systems are not only about revenue; they reveal whose interests are protected and whose burdens are normalised. One feature of India’s contemporary debate is the uneasy perception that ordinary individual taxpayers often feel squeezed, while large concessions for selected corporate categories are defended as “growth-friendly”. The economic logic for corporate concessions is well-known: competitiveness attracts investment; investment creates jobs; jobs create prosperity. Sometimes that chain works. But the democratic test is not the logic of a policy memo. The test is the outcome: does the overall tax-and-transfer system reduce inequality and visibly improve public goods, or does it quietly entrench concentration while the language of development grows ever more ornate?

Citizens are entitled to ask why tax concessions are often described as an investment in the future, while public expenditure on health, education, and basic urban services is treated as a cost to be contained. If development is truly about people, the state cannot be run as though citizens are incidental to the economy rather than its purpose.

A practical definition that fits a five-year democracy

So what should citizens demand when politicians speak in the language of Viksit Bharat and “Developed India”?

Not the abandonment of long-term ambition—but the translation of ambition into a five-year contract. Development must be defined in measurable terms, set against a baseline, and audited annually. If a government wants to speak of 2047, it must also tell voters what it will deliver by the end of its current term—because only that is morally and constitutionally testable.

A credible development definition for a five-year democracy can be built around outcomes that a citizen recognises and can verify:

Nutrition and basic security: reduced distress dependence, better child nutrition, and reliable last-mile delivery where support remains necessary.

Health outcomes, not ribbon-cuttings: maternal and infant mortality, catastrophic health expenditure, and quality primary healthcare.

Learning and skills, not enrolment theatre: foundational literacy and numeracy, school completion, and employable skills.

Jobs and real incomes: broad-based employment and wage growth that outpaces inflation for ordinary workers—not just headline “start-up” narratives.

Equity and dignity in public services: water, sanitation, air quality, safety, mobility, and predictable public administration that does not require influence to function.

SC and ST inclusive development: measurable closing of gaps in schooling, health access, land and livelihood security, quality housing, and representation in public employment and local institutions—so inclusion is not ceremonial but outcome-based.

Rights of religious and linguistic minorities: equal citizenship in daily life—protection from discrimination and hate, fair access to public services and opportunities, and credible safeguards so minorities do not feel reduced to second-rate citizens.

This is not ideology; it is governance. It describes what development feels like in a household and a neighbourhood.

Pin the promise to the record

This is where the citizen’s democratic power must be exercised. When a government speaks in terms of a distant, luminous future, the voter must pull it back to earth: compare the promise to the record since the day it first came to power; measure delivery against declared targets; ask what improved, for whom, and at what cost.

This need not be an indictment of any particular leader or era. Every ruling party, across decades, has used the language of development. Every opposition has accused the incumbent of failing it. The deeper point is institutional: when development becomes a slogan rather than a scoreboard, democracy is turned upside down. Citizens are asked to applaud the vision instead of auditing the performance.

India does not need fewer dreams. It needs fewer evasions. The next time a politician says Viksit Bharat, the citizen’s reply should be simple and relentless: define it, quantify it, time-limit it, publish annual milestones, and tell us what you will deliver before you ask for another mandate.

Development is indeed a concept. It is also a process. But in a five-year democracy, it must never be allowed to become a mirage—a shimmering horizon that keeps retreating while the voter is told to admire the distance.