When I wrote “Gangsters or Terrorists?”, I argued clearly that law and order and organised crime would become the defining political issue in Punjab well before the 2027 elections. https://gpsmann.substack.com/p/gangsters-or-terrorists-canadian?r=3598n2

When I wrote “Gangsters or Terrorists?”, I argued clearly that law and order and organised crime would become the defining political issue in Punjab well before the 2027 elections. https://gpsmann.substack.com/p/gangsters-or-terrorists-canadian?r=3598n2

That assessment was not theoretical; it reflected what citizens were already experiencing extortion calls, targeted shootings, and a growing culture of fear. It is therefore welcome that the government has finally acknowledged the problem. But recognition alone is not enough. At this stage, only action will speak; not press notes or curated statistics.

Punjab’s gangster problem is no longer isolated crimes. It has matured into a well oiled ecosystem. Criminal networks today operate through cross-border handlers, encrypted communication, and sophisticated financial channels.

Businessmen, professionals, traders, and even ordinary families have been targeted. This has damaged not just public safety but also investor confidence and social trust.

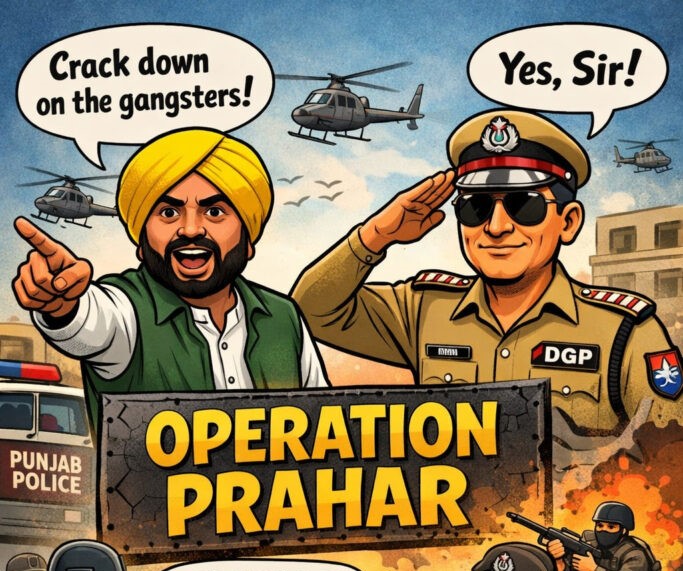

The launch of Operation Prahar marks an important shift in approach. The deployment of over 12,000 personnel across more than 2,000 teams, and action against networks linked to around 60 foreign-based gangsters, indicates that the scale of the problem is finally being acknowledged. Targeting aides, facilitators, and local support systems is essential, because gangs survive not only through their leaders but through the infrastructure that sustains them.

Credit must be given where it is due. The Punjab Police remains one of the most professional forces in the country. Given a clear political mandate and protection from interference, it has the capacity to deliver results.

The problem has not been capability, but politicisation. Selective enforcement and short-term political calculations have weakened the basic structure for the force.

Internal vigilance is always critical. There are black sheep in every institution, and in policing, even a few can compromise entire operations. This is particularly relevant in extortion cases, where there are persistent allegations that victim identification is sometimes enabled locally through leaks or informal networks. No serious anti-extortion drive can succeed unless these internal vulnerabilities are addressed without hesitation.

Equally important is the role of the Central Government. Several major gangsters are lodged in central prisons outside Punjab, in Dibrugarh, in Gujarat, yet continue to operate their networks from behind bars. If extortion calls and violent instructions can be issued from jail, then prison administration and surveillance have clearly failed.

A state-level crackdown will remain incomplete unless gang leadership is neutralised through firm coordination with the Centre.

It is politically sensible that the Aam Aadmi Party has recognised that law and order cannot be treated as a secondary issue. By 2027, voters will not ask who issued the strongest statements. They will ask a simpler question: did we feel safer?

Punjab needs sustained, depoliticised enforcement of law.

Late action is better than none. But in the end, only firm actions will count