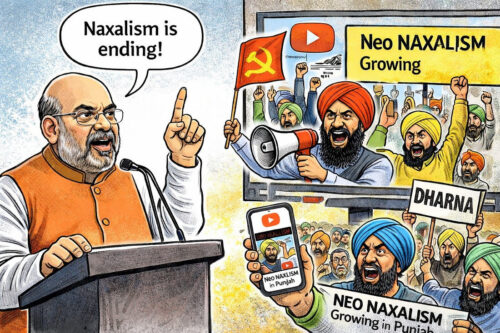

Union Home Minister Amit Shah has asserted that Naxalism in India has reached the verge of extinction. From the narrow standpoint of armed Maoist violence in parts of central India, this claim may appear defensible. Sustained security operations have weakened insurgent networks and reduced their capacity to wage an armed challenge to the state. Yet this conclusion rests on an unduly restrictive understanding of what Naxalism actually is.

Union Home Minister Amit Shah has asserted that Naxalism in India has reached the verge of extinction. From the narrow standpoint of armed Maoist violence in parts of central India, this claim may appear defensible. Sustained security operations have weakened insurgent networks and reduced their capacity to wage an armed challenge to the state. Yet this conclusion rests on an unduly restrictive understanding of what Naxalism actually is.

Naxalism is not merely a .303 gun. It is a method—an ideology—and ideologies do not die so easily. They mutate, adapt, and change form.

Today, Naxalism is largely gunless—but far from powerless. It has gone high-tech. It now operates through YouTube channels, Instagram reels, podcasts, campus meetings, protest sites, and carefully curated digital outrage. Its reach is wider, its language softer, and its intent often disguised as activism or dissent. A gun kills one; a YouTube podcast can mislead thousands in minutes. Thousands brain dead inminutes!

At its core, Naxalism is an ideology-driven strategy to delegitimise and defame the state, create permanent social unrest, block development, and convert grievance into a political weapon. It thrives on creatively crafted false narratives, romanticised victimhood, and the systematic instigation of youth and marginalised sections—convincing them that disruption itself is resistance and stagnation is virtue. By this definition, Naxalism has not vanished; it has evolved.

Punjab today does not face forest-based insurgency. What it confronts is a subtler variant—Neo Naxalism or Urban Naxalism. The battlefield is no longer remote jungles but universities, seminar rooms, social media platforms, toll plazas, protest sites, and under-construction development projects. The tools are not rifles but slogans, selective outrage, and relentless propaganda. The objective remains unchanged: obstruct infrastructure, demonise industry, paralyse governance, and deny economic progress any moral legitimacy. This is especially worrying given Punjab’s own brush with violent Naxalism in the early 1970s.

Universities, meant to be spaces of inquiry and intellectual rigour, are increasingly becoming breeding grounds for disruptive absolutism. Dissent is encouraged, but debate is shut down. “My way or the highway” becomes the new doctrine; logic is the first casualty. Students are mobilised not to critically examine policy, but to reject development itself as inherently exploitative. Narrative-building has become sophisticated, instant, and emotionally potent—designed to strike at a public eager to outsource blame.

Punjab offers this ideology an additional shield. When confronted, disruption often hides behind farmers, and when required, behind religion. Identity becomes armour. Religious symbolism and cultural vocabulary are deployed to protect obstruction from scrutiny. This is a uniquely dangerous turn.

This is not democratic protest. It is ideological sabotage masquerading as free speech.

Punjab’s crisis is not one of resources or talent, but of arrested momentum. A state cannot survive on agitation alone. Roads, industries, jobs, education, innovation, and technology cannot be built on perpetual hostility to growth—nor by labelling every developmental initiative a deep conspiracy.

Armed Naxalism sought to overthrow the state through violence. Neo Naxalism seeks to hollow it out by making governance impossible—by delegitimising it internally and defaming it externally. Recognising this shift is not intolerance; it is a necessity.

Naxalism may be retreating from the jungles. But unless its new urban, academic, and digital avatars are confronted honestly, it will continue to thrive—quietly, respectably, and disastrously, hiding behind farmers or faith.