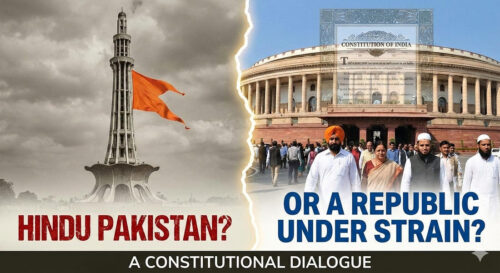

Ramachandra Guha’s recent YouTube interview to Karan Thapar for The Wire is pitched as an alarm bell. It is also, unmistakably, a moral indictment. Guha argues that India in 2026 is “as close to being a Hindu Pakistan as it has ever been”: not because the Constitution has changed in its text, but because the lived meaning of equal citizenship is, in his view, being hollowed out through politics, institutions, symbolism, popular culture and street-level impunity. It is a powerful formulation, designed to shock the complacent and shame the triumphalist. Yet precisely because it is framed in absolutist terms—“Hindus have rights and Muslims don’t”, “medieval barbarism”—it also invites a careful rebuttal: one that neither minimises real anxieties of minorities nor accepts, without scrutiny, a sweeping analogy that can itself become a caricature.

Ramachandra Guha’s recent YouTube interview to Karan Thapar for The Wire is pitched as an alarm bell. It is also, unmistakably, a moral indictment. Guha argues that India in 2026 is “as close to being a Hindu Pakistan as it has ever been”: not because the Constitution has changed in its text, but because the lived meaning of equal citizenship is, in his view, being hollowed out through politics, institutions, symbolism, popular culture and street-level impunity. It is a powerful formulation, designed to shock the complacent and shame the triumphalist. Yet precisely because it is framed in absolutist terms—“Hindus have rights and Muslims don’t”, “medieval barbarism”—it also invites a careful rebuttal: one that neither minimises real anxieties of minorities nor accepts, without scrutiny, a sweeping analogy that can itself become a caricature.

Guha’s Warning: The Case for a “Hindu Pakistan”

Guha’s argument unfolds in a deliberate sequence. First, he points to representation: the absence of Muslims from the national executive, the BJP’s failure to elect Muslim MPs over three elections, and the striking dearth of Muslim legislators in large states such as Uttar Pradesh. From this, he infers an underlying theory of citizenship: Muslims are treated not as equal citizens, but as subordinate “subjects”. Second, he extends the charge beyond elected office to what he calls the deeper state: the civil services, diplomatic corps, armed forces and judiciary, where he claims a systematic exclusion of capable Muslims from positions of authority, echoing—ironically, he says—the worst minority practices of Pakistan and Bangladesh. Third, he turns to symbolism: saffronised political theatre, public temple visits by senior constitutional authorities, and majoritarian signalling in public life. Fourth, he indicts institutions—courts, police, election regulators and media—for looking away when majoritarian rhetoric crosses constitutional lines. Fifth, he cites popular culture, especially Bollywood, as a domain where plural India is allegedly being replaced by suspicion and stereotype. Finally, he describes everyday humiliations, violence and impunity, arguing that the very absence of shame—indeed, the presence of public exultation—marks a descent into “modern contemporary barbarism”. He attributes the long arc to a historical chain: the growth of Hindutva ideas over decades, Congress errors and “appeasement”, Rajiv Gandhi’s reversals in the Shah Bano moment and the Ayodhya lock-opening, and then the unchecked ideological drive and administrative competence of the Modi–Shah axis.

Why the Analogy Overreaches: Constitutional Design Versus Political Mood

Why the Analogy Overreaches: Constitutional Design Versus Political Mood

That is a formidable case in rhetoric. But as a claim about constitutional India, it is too blunt to be wholly true, and too consequential to be accepted without careful calibration. The “Hindu Pakistan” analogy is the most problematic part. Pakistan’s founding premise was explicitly anchored in religious nationalism; its constitutional identity and political sociology were formed around a state preference for one faith. India’s constitutional premise is the opposite: citizenship, in law, is not mediated by religion; fundamental rights and equality guarantees apply across faiths; and courts routinely invalidate state action that violates these guarantees. None of this is to deny that discrimination can exist; it is to insist that discrimination is not the constitutional design, and that institutional remedies—however imperfect—remain available and are often invoked.

Even if a present dispensation were, at least arithmetically, to command a parliamentary majority large enough to pass constitutional amendments, India is not an open field for constitutional redesign. A pivotal safeguard lies in the Supreme Court’s doctrine flowing from Kesavananda Bharati: Parliament’s constituent power does not extend to altering or destroying the “basic structure” of the Constitution. In practical terms, this means that features such as the democratic and republican character of the state, constitutionalism and the rule of law, equality, and the secular character of the Republic are widely understood as belonging to that protected core. These are not mere ornamental phrases that can be rewritten at will; they are structural commitments. It is precisely because this doctrine exists that alarmist claims of an imminent constitutional conversion into a theocratic state should be treated with caution. One may fear social majoritarianism, administrative bias, or symbolic capture—but a wholesale legal overthrow of the Republic’s foundational character is not readily available, even through the dubious route of constitutional amendments. One must hope that Kesavananda Bharati continues to stand as a vigilant constitutional bulwark.

A constitutional republic does not become its opposite simply because the politics of the day is coarse, or because the ruling party’s candidate-selection is morally repugnant. The better question is: are we witnessing episodic prejudice, systemic majoritarian capture, or a messy but contestable struggle over the meaning of secular citizenship?

Representation: A Political Failure, Not a Change in Citizenship

Start with Guha’s first plank: representation. It is true that political parties may behave cynically and exclude minorities from tickets. That is a democratic failure of imagination and courage. But it does not follow that Muslims are legally reduced to “subjects”. In a democracy, parties represent coalitions; they also pander. The remedy to exclusion in party nominations is not to declare a constitutional rupture, but to demand broader internal party democracy, more diverse candidate pipelines, and the active engagement of civil society and voters who punish exclusion. It is also worth remembering that the absence of Muslims in one party’s parliamentary ranks does not mean Muslims are absent from Parliament. It means that a particular party has chosen polarising electoral mathematics. That can corrode fraternity, but it is not the same as a legal architecture of second-class citizenship.

Institutions and the “Deep State”: Where Evidence Must Be Sharper

Guha’s second plank—systematic exclusion from institutions—requires more evidence than is offered in an interview. The Indian state has always been uneven in representation across communities, regions and classes. Under-representation of Muslims in parts of the bureaucracy and police is a documented social concern and should be addressed through fair recruitment, coaching access, and anti-discrimination enforcement. Yet the leap from under-representation to a coordinated, ideological “elimination” of Muslims from authority is a serious allegation. It demands patterns, data, and institutional causation, not a rhetorical recollection of better times. Moreover, one must be cautious about romanticising the past. The earlier presence of eminent Muslim officials was important and should inspire confidence, but it did not mean prejudice was absent then; nor does a contemporary deficit automatically prove a new constitutional order.

Symbolism and Statecraft: Faith Is Not the Issue—Hierarchy Is

Third, symbolism. Here Guha has a stronger point, because symbolism shapes civic psychology. When the state’s most visible faces appear to fuse governance with religiosity, minorities can reasonably feel that the public square is not equally theirs. Yet symbolism cuts two ways. A secular state does not require public officials to be personally irreligious; it requires them, in office, to act without religious favouritism and to uphold equality. The line is crossed when state power and state resources are deployed to privilege one faith, or when constitutional offices are used to signal hierarchy. The correct remedy is restraint, constitutional etiquette, and an insistence that public ceremonies reflect India’s plural inheritance—not the policing of private belief.

Law and Order: The Republic Must Not Look Away

Fourth, the charge of institutional silence. Here too, there is legitimate anxiety. Hate speech, communal insinuations, and selective enforcement corrode the rule of law. As someone who has spent a life inside government, I can say that when local administration becomes timid before mobs, or when policing becomes politically performative, the first casualty is not merely a minority community; it is the credibility of the state itself. But again, the diagnosis must be precise. India is not uniformly “lawless”, and the institutional record is not uniformly complicit. Courts have intervened in many instances; civil society has litigated; media and citizens have exposed abuses. The picture is uneven—troubling in some regions, better in others—and that very unevenness is evidence against a monolithic “Hindu Pakistan” thesis.

Popular Culture: A Contested Space, Not a Conquered One

Fifth, the culture war around Bollywood and popular passions. One can accept that propaganda can creep into entertainment without concluding that plural culture has collapsed. Indian culture remains stubbornly composite: language, music, food, commerce, and everyday neighbourliness continue to resist neat communal compartments. The danger lies not in one film or one speech but in the normalisation of stereotype—when suspicion becomes default. That danger is real, but it is a civilisational contest within India, not a completed transformation.

The Hardest Truth: Humiliation, Violence, and the Poison of Triumphalism

Where Guha’s argument is most morally compelling—and where rebuttal must be most careful—is on everyday humiliation and violence. Any citizen beaten or bullied because of faith is an indictment of our fraternity. If, in some places, social media triumphalism now accompanies cruelty, that is a grave cultural degeneration. A Sikh knows, perhaps more viscerally than most, what it means for the state or the street to turn hostile and for prejudice to dress itself as righteousness. If Muslims today feel an atmosphere of fear, the Republic must treat that feeling as a governance problem, not merely a public-relations irritant.

Appeasement Versus Equality: Learning the Right Lessons From Shah Bano

At this point, the rebuttal must also confront Guha’s historical chain: “appeasement” followed by “backlash”. There is truth here, though it is often weaponised. Rajiv Gandhi’s handling of Shah Bano did signal political weakness, and it came at the cost of Muslim women and the constitutional promise of gender equality. Equally, the pathologies of communal politics were not invented in 1986, nor were they absent in earlier decades. But the more important point is what follows from that history. A mature secularism does not swing between appeasement and majoritarian correction. It consistently applies constitutional principle: equality, dignity, and reform through law. The aim is not to “teach a community a lesson” but to protect individual rights within every community, especially of women and the vulnerable, while preserving legitimate cultural autonomy where it does not violate equality.

Reform Without Revenge: The Test for UCC and Other “Parity Corrections”

This is where Guha’s framing can be contested most constructively. If the question is: has the post-2014 state sometimes pursued parity-corrections—ending the Haj subsidy, invalidating instant triple talaq, speaking openly of a Uniform Civil Code, questioning anomalies in special regimes? The answer is yes. Many of these steps can be defended as constitutional housekeeping, not religious triumph. At the same time, the manner in which reforms are communicated matters. Reforms cannot be packaged as civilisational revenge; otherwise, even good policy becomes bad politics. A Uniform Civil Code, if it is to honour constitutionalism, must be built as a gender-just, rights-based civil code emerging from consultation, not as a majoritarian slogan aimed at one community. Likewise, when integrationist steps are taken—whether in special constitutional arrangements or citizenship policy—they must be accompanied by reassurance, procedural fairness, and a visible commitment to equal dignity.

Conclusion: A Republic of Equal Citizens, Not Equal Fears

So what would a balanced conclusion look like—one that neither endorses Guha’s bleak finality nor dismisses the anxieties that animate his warning? India’s international engagement, economic prospects, and the aspiration of a confident society are real positives. But constitutional patriotism is not measured only in GDP growth or global stature; it is measured in how safe the weakest citizen feels in the bazaar, in the police station, and in the classroom. A government does not prove secularism by proclaiming it; it proves it by impartial law enforcement, swift punishment for communal violence, and equal access to opportunity. Minorities—including Muslims—need to see not only the end of old distortions but the active presence of new trust: fair representation in public employment through merit and access, targeted development without patronage, protection of places of worship from vandalism, and a civic language that rejects collective blame.

Whither Federalism?

Yet it would be intellectually incomplete—and perhaps strategically unwise—to confine our republican anxieties only to the majority–minority axis. There is another drift which can be just as corrosive to the constitutional idea of India: increasing centralisation and a thinning of federalism, in letter as well as in spirit. The Constitution was framed as a Union, but it was never meant to become an administrative monoculture. When states begin to feel that their constitutional space is under strain—whether through an overbearing use of the Union’s fiscal and administrative levers, or through a political culture that treats federal negotiation as inconvenience rather than necessity—the Republic itself is weakened. This becomes sharper in the contemporary north–south divide debates: if the future reworking of Lok Sabha seats state-wise is perceived to penalise states that have achieved demographic stabilisation, or if the Finance Commission’s devolution and the principles of horizontal distribution are viewed as persistently inequitable, resentment will not remain merely economic. It will become constitutional and emotional—feeding a narrative that some regions are being structurally subordinated within the Union. A republic can survive contentious identity debates; it struggles when federating units begin to doubt the fairness of the compact.

The answer, therefore, is neither Guha’s despairing analogy nor any complacent claim that “everything is fine”. The answer is constitutional discipline on all fronts: reform where personal laws injure equality; neutrality where the state is tempted by sectarian symbolism; firmness where mobs test the law; empathy where citizens feel excluded; and, equally, a renewed fidelity to cooperative federalism, where states are treated as partners, not provincial outposts. If India can hold these together—confidence without arrogance, reform without humiliation, national pride without religious hierarchy, and a Union that honours the dignity of its states—then it will not become anyone’s mirror image. It will remain what it promised to be: a Republic of equal citizens, sustained by the rule of law, and strengthened—not threatened—by its plural society and its federal design.