Today’s “Jago Punjab” appeal (full page ad in The Tribune, page 5) issued by Sardar Swaran Singh Boparai, a Kirti Chakra awardee, former Punjab cadre IAS officer and Vice-Chancellor, deserves genuine appreciation. It is rare to see someone of his stature use a solemn occasion—the 350th martyrdom anniversary of Guru Tegh Bahadur Sahib—to speak so unambiguously for Punjab’s constitutional and economic rights. The advertisement gives voice to long-standing grievances over river waters, Chandigarh, fiscal dues and the neglect of Punjab’s special circumstances. Many Punjabis, across party lines, instinctively agree with the sense of historic unfairness that runs through his text.

Today’s “Jago Punjab” appeal (full page ad in The Tribune, page 5) issued by Sardar Swaran Singh Boparai, a Kirti Chakra awardee, former Punjab cadre IAS officer and Vice-Chancellor, deserves genuine appreciation. It is rare to see someone of his stature use a solemn occasion—the 350th martyrdom anniversary of Guru Tegh Bahadur Sahib—to speak so unambiguously for Punjab’s constitutional and economic rights. The advertisement gives voice to long-standing grievances over river waters, Chandigarh, fiscal dues and the neglect of Punjab’s special circumstances. Many Punjabis, across party lines, instinctively agree with the sense of historic unfairness that runs through his text.

2. The Problem with a Single-Point Agenda

These questions are not imaginary. The secretive decisions on river waters, the incomplete reorganisation of Punjab, the unresolved status of Chandigarh and the failure to compensate Punjab for its role in feeding the nation are real disputes. They must remain firmly on the agenda and continue to be pursued through constitutional, political and public platforms. If senior citizens like Boparai did not keep reminding the country of these issues, New Delhi’s convenient amnesia would have buried them long ago. Yet there is a danger in allowing these grievances to become the only agenda around which Punjab’s politics and public discourse revolve. If every debate begins and ends with water, territory and historical injustice, we risk becoming prisoners of our own past.

3. Questions Punjab Must Ask Itself

Delhi does owe Punjab answers—but Punjab also owes some answers to itself. It is easier to point to what others have done to us than to ask what we have done, or failed to do, with the powers already in our hands. For decades, Punjab has had a fully elected government, its own civil service, police, universities and local bodies. No Union government stopped us from running honest police stations, clean revenue offices or efficient municipalities. It was not Delhi that encouraged arbitrary postings, political interference in the police, or the casual destruction of institutional norms. These were choices made in Chandigarh and in our districts, often with the silent approval of voters who rewarded patronage more than performance.

4. Governance Failures Close to Home

Unless we repair our own institutions, no settlement on river waters will by itself cure the rot. Administrative reforms, transparent recruitments, professional policing and accountable local government are entirely within the state’s control. Yet, time and again, Punjab has allowed short-term political convenience to trump long-term institution-building. Even the best constitutional award from the Centre will mean little if files still move only with favours, if tenders are seen as opportunities for cuts, and if public offices remain more feared than respected. The first clean-up operation has to be within our own secretariats, police lines and district offices, where the rot of patronage and impunity has been allowed to harden over decades.

5. Education: A Mirror We Avoid

Education is another mirror we prefer not to look into. We blame the Centre for not giving enough funds, but billions of rupees allocated to school and higher education have been spent with very mixed results. Parents still fight to send their children to private schools; university campuses are plagued by factional politics and declining academic standards; technical education is too often a licence shop. None of this can be blamed on Article 246 or the Reorganisation Act. These are failures of planning, supervision and local leadership. A generation is leaving Punjab not only because there are few jobs, but because they are not confident our institutions can prepare them for a competitive world. An underperforming school system feeds directly into the vulnerabilities that drugs and crime later exploit.

6. Agriculture: Pride, Dependence and Ecological Peril

Agriculture, the pride of Punjab, is in a similar bind. The “Jago Punjab” document rightly underlines how the country benefited from Punjab’s wheat and paddy and how little genuine gratitude we received in return. But even as we fight for a fair MSP regime and for our share of river waters, we have to confront the uncomfortable truth that continuing with the present cropping pattern is ecologically suicidal. The falling water table, degrading soil and rising input costs cannot be reversed solely by central concessions. They require a painful but necessary shift towards diversification, agro-processing, dairying and value addition. This needs courage from farmers, honest advice from agricultural scientists, and consistent support from the state government. No Prime Minister can make that decision for us. If we fail here, rural distress becomes fertile ground for drugs, moneylending mafias and criminal networks.

7. Drugs, Mafia and the New Gangster Culture

Nowhere is Punjab’s internal crisis more visible than in the spread of drugs and the rise of gangsterism. What began as a silent epidemic has, over the years, acquired the armour of organised crime: supply chains that stretch beyond the border, local peddlers embedded in villages, and a drug mafia that cannot operate without protection from corrupt elements in politics, policing and officialdom. An entire ecosystem of easy money, flashy vehicles and weapon-laden social media profiles glamorises this pathology for the young.

The recent wave of gang wars, contract killings and extortion rackets is not an accident; it is the logical outcome of years of neglect and complicity. When FIRs can be “managed”, when known gangsters find political patrons, when social media openly celebrates gun-toting singers and influencers, we should not pretend that the only injustice done to Punjab flows from Delhi. The first responsibility for breaking the spine of the drug and crime nexus lies with the state government, the police leadership and, ultimately, with society itself, which must stop treating these trends as entertainment or distant gossip.

8. A Society Under Strain

The drug menace and gangsterism do not exist in isolation; they feed off broader social fissures. Gun culture, traffic indiscipline, gender violence and caste-based discrimination are not imported policies; they grow in our own mohallas and villages. The Centre may help with border vigilance or national-level agencies, but the first line of defence is still the local police station, the panchayat, the gurdwara committee and the family. When we look away from an addict in our home, when we tolerate ostentatious weapon displays at weddings, when we romanticise gangsters in our popular culture, when we allow dowry and domestic abuse to continue as “private matters”, we are weakening Punjab from within far more than any water-sharing arrangement ever could.

9. Diaspora: From Outrage to Ownership

The diaspora too must reflect. Overseas Punjabis have contributed generously to gurdwaras, schools and charities, and their emotional bond with the homeland is undeniable. But a part of the diaspora also lives in a permanent state of digital outrage—forwarding provocative videos, financing factional politics and demanding maximalist positions from the safety of foreign passports. Sometimes, diaspora money and admiration have also romanticised the very gangsters and dubious “icons” who are tearing apart the social fabric at home.

If “Jago Punjab” is to become a serious programme of renewal, the diaspora has to move from sentiment to strategy: investing in research, entrepreneurship, skilling and innovation in Punjab rather than only in real estate or religious prestige projects—and consciously distancing itself from the culture of guns, easy money and performative extremism. The diaspora can bring cutting-edge ideas on technology, governance and enterprise; that is the real remittance Punjab now needs.

10. Governments Must Do More Than Blame

The state government, whichever party leads it, also has to rise above reactive politics. It is easy to pass resolutions blaming the Centre; it is harder to reform power utilities, rationalise subsidies, enforce building by-laws, clean up municipal finances—and wage a sustained, professional war against the drug and crime mafias. When the administration fails to collect property tax or electricity dues, or quietly transfers away officers who take on entrenched interests, it is not because Delhi ordered us to be lax; it is because our political class prefers short-term popularity over long-term stability. A mature Punjab agenda must therefore include fiscal discipline, transparent appointments, time-bound delivery of services, a professionalised police service and a credible, depoliticised anti-drug strategy. Without this foundation, any additional share of river waters or central funds will simply be wasted.

11. Citizens Beyond Complaint

Punjab’s people also have a role beyond voting every five years. Citizens who complain about corruption must be willing to refuse shortcuts themselves. Parents who lament the state of government schools should participate in school management committees and hold teachers—and local politicians—accountable. Community leaders must stop inviting or glorifying performers and influencers who normalise drugs, misogyny and violence. Professionals and entrepreneurs must come forward to mentor start-ups, support internships and build networks that create employment within Punjab—giving the youth an alternative to the false glamour of the drug and crime economy. Civil society has to broaden its focus from protest alone to sustained engagement on issues like environment, urban planning and public health. Without citizen ownership, even the best policies will remain paper promises.

12. Generational Change and the Role of Elders

It is in this wider context that the “Jago Punjab” call has to be located. With the greatest respect, Boparai Sahib is a 1964 batch IAS officer who retired from active service over two decades ago. In that sense, he is that much late in raising this particular banner. Better late than never, of course; his intervention still has moral weight and historical memory behind it. But it is now time for the younger generation of Punjabis—farmers’ leaders, professionals, students, entrepreneurs, artists—to come forward and articulate their views and aspirations in their own idiom, especially on the burning questions of drugs, crime and the future of work.

Personages like Boparai Sahib can and should guide, mentor and bless this process, helping the youth avoid the mistakes of the past. The one thing they should not insist on is remaining in the driver’s seat. A truly awakened Punjab must allow its young to steer, while its elders provide the map and the cautionary tales.

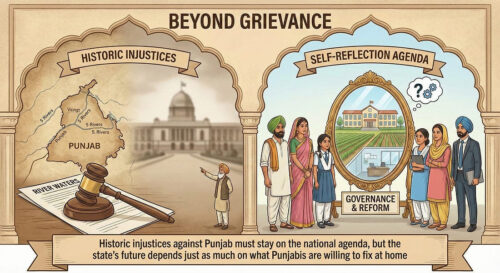

13. A Twin-Track Strategy for Punjab

None of this means abandoning the demands highlighted by Boparai sahib and the Jago Punjab Forum. On the contrary, pursuing those issues becomes more credible when we show that, within the powers we already possess, we are capable of good governance and responsible citizenship. New Delhi listens differently to a state that is fiscally disciplined, socially cohesive, administratively efficient and visibly serious about tackling drugs and gangsterism than to one that appears perpetually chaotic and self-defeating. Moral authority comes not only from historical sacrifice but also from present-day conduct. We therefore need a twin-track approach: on one track, Punjab continues to press—firmly but constitutionally—for justice on river waters, territorial claims, overdue compensation and a more respectful federal relationship; on the other, Punjab undertakes a rigorous programme of self-correction.

14. From Grievance to Construction

Guru Tegh Bahadur’s martyrdom, invoked in the “Jago Punjab” appeal, was not only an act of resistance; it was also an act of responsibility—standing up for the oppressed even when they were not his own people. Remembering him today should inspire us not only to confront external injustice but also to face uncomfortable truths about ourselves. If this advertisement becomes merely another document in our long list of grievances, we will have wasted an opportunity. If, however, we treat it as a wake-up call to introspection as well as agitation, then “Jago Punjab” can acquire a deeper meaning. The time has come for Punjab to move from a politics of complaint to a politics of construction. Our history gives us every right to demand fairness from the rest of India. But our future depends just as much on what we are prepared to do for ourselves.

Share The KBS Chronicle

You’re currently a free subscriber to The KBS Chronicle. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.

Upgrade to paid

Like

Comment

Restack

© 2025 KBS Sidhu

Unsubscribe

Get the appStart writing