Author Note:This essay is a hypothesis at the intersection of AI and robotics, economics, sociology, and the democratisation of artificial intelligence. It analyses how shifting labour scarcity may reorder the economic value of occupations and, in turn, weaken the occupational foundations of hierarchy. Nothing here should be read as a moral judgement: no caste, varna, or occupation is being portrayed as superior or inferior.

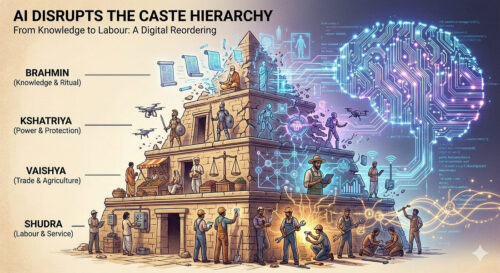

The caste system is usually described as a rigid hereditary hierarchy. Yet its oldest logic—the varna framework—was, at least in principle, occupational: Brahmins handled knowledge and ritual; Kshatriyas wielded coercive power; Vaishyas managed trade and agriculture; Shudras provided labour and services. That occupational scaffolding is now heading for a collision with artificial intelligence and automation.

Here is the counterintuitive irony. The groups historically perched at the top are likely to lose economic relevance first, because their core functions are information-heavy and rule-governed—precisely what AI is best at. Those placed at the bottom, whose work is physical, site-specific, and messy, may find their labour growing scarcer and therefore more valuable. This is not a sermon about justice. It is an assessment of which forms of work are easiest to automate, and which remain stubbornly resistant.

The Brahmin predicament: when AI becomes the ultimate priest

The Brahmin’s traditional advantage rested on exclusive access to specialised knowledge—texts, mantras, ritual procedure, interpretation, and counsel. That monopoly is collapsing.

Generative AI can already recite, translate, summarise, and cross-reference religious literature at scale. It can explain doctrine in plain language, in multiple tongues, and tailor guidance to an individual’s question with unfailing patience. A system trained on centuries of commentary can connect obscure passages faster than any scholar, and do it at negligible cost.

What is happening to adjacent knowledge professions is a preview. Law, accounting, compliance, and advisory work are being re-engineered around AI assistance: the repetitive “interpret–apply–draft” loop is increasingly machine-mediated. The Brahmin’s historical claim to authority—custodianship of knowledge—weakens in a world where knowledge is abundant, searchable, and personalised on demand.

A villager with a phone will be able to consult an AI that has digested vast religious and philosophical corpora and can respond instantly in the user’s mother tongue. When guidance becomes a utility, the priestly gatekeeper begins to look less like a guardian and more like an unnecessary intermediary.

The Kshatriya crisis: warriors in an age of drones

The Kshatriya’s function was martial: warfare, protection, political dominion—today mirrored in the military, police, and security apparatus.

But modern coercive power is being reorganised around machines. AI-enabled surveillance, predictive systems, autonomous or semi-autonomous drones, and remote operations reduce the demand for human presence in direct conflict. The decisive advantages shift from physical prowess and battlefield intuition to software, sensors, networks, procurement, and command-and-control systems.

This is a subtle form of displacement. It is not that every soldier is replaced tomorrow; it is that institutional investment tilts steadily away from manpower and towards machines. Defence budgets drift from salaries to platforms; from foot patrols to sensor grids; from bodies to capability. In that world, the classic warrior ethos is no longer the centre of gravity. The new “martial” elite is technical, distributed, and remote.

The Vaishya squeeze: when merchants meet algorithms

The Vaishya’s power historically flowed from commerce: judging demand, sourcing goods, negotiating, moving products, and matching buyers to sellers. The fuel for that power was information asymmetry—knowing what others did not.

AI is built to crush asymmetry. Platforms already use algorithms to forecast demand, optimise inventory, set prices dynamically, target customers, assess credit, and manage relationships. Procurement and distribution are increasingly digitised end-to-end. The modern merchant’s core tasks—matching, persuasion, and routine judgement—are exactly the tasks machine learning automates.

The deeper threat is not merely job loss; it is the erosion of advantage. When market intelligence becomes widely available and continuously optimised, competition shifts towards scale and capital—favouring large platforms and organised supply chains over the small, relationship-based trader. The merchant class does not disappear overnight, but its traditional basis of leverage is steadily hollowed out.

The farmer’s reprieve: mechanisation without elimination

Agriculture sits awkwardly in this picture because it can be technologically enhanced without being fully replaced.

AI is already changing farming through precision advisory, weather and pest prediction, crop planning, irrigation optimisation, and market intelligence. These tools can raise yields and reduce waste. Yet farming remains “mechanisation-resistant” in practice: planting, harvesting, sorting, and the thousand improvisations that real fields demand still rely on human labour and judgement—especially on small and medium holdings where full robotics is not economically viable.

So the farmer is more likely to be augmented than eliminated in the medium term. AI may lift productivity and incomes in pockets; it is less likely to render farmers obsolete quickly. The work survives not because it is high-status, but because the physical world is expensive to automate at scale.

The Shudra paradox: when scarcity becomes virtue

The Shudras—labourers, artisans, tradespeople, service providers—were historically assigned the lowest social value. Yet their work maps poorly onto near-term automation.

Skilled trades such as electrical work, plumbing, welding, HVAC, construction, and maintenance are defined by variability: different sites, unexpected constraints, old infrastructure, human error, weather, and improvisation. Robots can assist, but replacing a competent technician in real-world conditions remains hard and costly.

Meanwhile, these trades are facing shortages. Infrastructure build-outs, housing demand, electrification, renewable energy, manufacturing, and data-centre expansion all depend on human hands. Even the gleaming future of AI requires concrete, steel, wiring, cooling, and maintenance—work done by the very occupations that sit lowest in the inherited hierarchy.

The result is a quiet reversal. Where knowledge work becomes cheaper through automation, hands-on competence becomes scarcer—and scarcity raises value. The Shudra’s labour, long treated as socially inferior, begins to acquire bargaining power because it is difficult to substitute.

Wage convergence: when hierarchies invert

Across many economies, labour markets are polarising. Routine middle-layer roles get squeezed, while high-end and hard-to-automate roles grow. But AI scrambles what “high-end” means. Many white-collar roles are high-status and credential-heavy, yet increasingly automatable. Many hands-on roles are treated as low-status, yet resilient and increasingly well-paid.

India adds another twist. Services contribute a large share of output but a much smaller share of employment, and the most globally competitive segments—IT, finance, professional services—employ relatively fewer people. These are precisely the segments most exposed to AI-led productivity shocks. At the same time, the economy is projected to need a vast expansion in blue-collar and skilled work to meet construction, manufacturing, and infrastructure goals.

This is how caste’s economic logic unravels. The system assumed that learning, ritual status, and “clean” work translated into income and authority. AI decouples status from earnings by commodifying information and standardising judgement. In parallel, it raises the premium on embodied skill—building, repairing, maintaining, adapting—work historically pushed down the hierarchy.

Why the physical world changes more slowly

A fair objection is that robotics will eventually automate trades too. In principle, yes. In practice, the timeline matters more than the destination.

Cognitive automation scales quickly because software is cheap to replicate. Physical automation is capital-intensive, fragile in chaotic environments, and expensive to maintain. A robot capable of reliably handling the endless variety of construction sites is far more complex than a model that drafts a memo. In the long transition between today’s AI and any hypothetical future of universal robotics, the physical economy will remain hungry for skilled human labour.

That interregnum may last decades—long enough to reshape careers, wages, and social status within a single generation.

What survives when the occupational logic collapses?

Caste is more than occupation. It is identity, marriage practice, social boundary, prejudice. Those may persist. But caste as an organising principle of economic life weakens when the jobs it historically mapped to are transformed.

If knowledge and interpretation become cheap and ubiquitous, priestly authority loses its economic base. If coercive power becomes technical and remote, martial status loses its grounding. If commerce is run by platforms and algorithms, traditional merchant leverage shrinks. If hands-on skill becomes scarce, the labouring classes gain economic weight.

None of this guarantees fairness. Wealth and networks will still matter. Inequality will still exist. The transition will be painful: displacement, retraining, resentment, and political churn. But the caste-based allocation of economic function—the idea that birth fixes livelihood and rank—becomes increasingly incoherent when machines reorder the labour market.

The paradox completed

AI will not dissolve caste through moral persuasion or social reform. It will erode caste through economic redundancy.

The supreme paradox of the coming decades is that the historically privileged—educated knowledge workers, professional intermediaries, ritual and advisory classes—face earlier and sharper automation shocks. Those long placed at the bottom—technicians, artisans, and hands-on workers—may be among the last to be displaced, and may even see rising wages and bargaining power in the meantime.

That does not end caste as culture. But it does threaten caste as economics. When occupations no longer map neatly onto inherited categories, and when income and leverage flow from scarcity rather than status, the old hierarchy loses its most practical justification.

An occupational hierarchy cannot survive when occupations themselves are being rewritten.