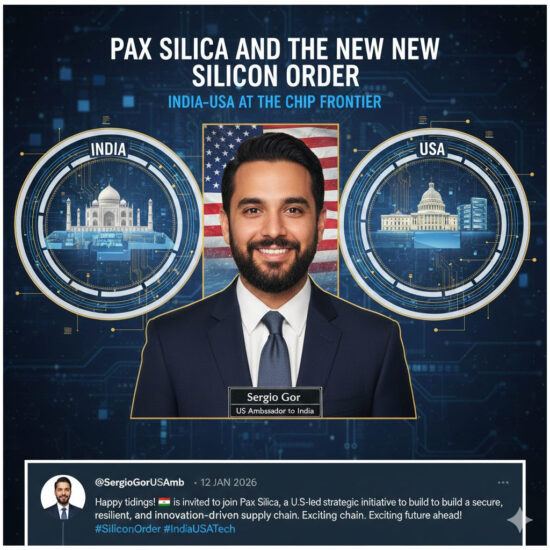

New Delhi: a brief tweet from the US Ambassador Sergio Gor announcing that India will be invited to join “Pax Silica, a U.S.-led strategic initiative to build a secure, resilient, and innovation-driven silicon supply chain” instantly turned an abstract technology coalition into a concrete Indian story. The message may be short, but it opens up a very long agenda. Coming even as the much-touted trade deal remains stuck in shallow waters after the US Commerce Secretary’s unguarded comments on a podcast, this move offers both a glimmer of hope and a possible point of inflection in India–US economic relations.

New Delhi: a brief tweet from the US Ambassador Sergio Gor announcing that India will be invited to join “Pax Silica, a U.S.-led strategic initiative to build a secure, resilient, and innovation-driven silicon supply chain” instantly turned an abstract technology coalition into a concrete Indian story. The message may be short, but it opens up a very long agenda. Coming even as the much-touted trade deal remains stuck in shallow waters after the US Commerce Secretary’s unguarded comments on a podcast, this move offers both a glimmer of hope and a possible point of inflection in India–US economic relations.

From trade static to tech signal

The context matters. For months, the bilateral conversation has been dominated by the “missing” trade deal, tariff niggles, digital taxes and the narrative that domestic politics on both sides have made meaningful economic bargains too costly. The Commerce Secretary’s suggestion that the deal stalled because Prime Minister Narendra Modi did not pick up the phone for President Donald Trump fed a perception of trivialisation—as if structural issues had been reduced to personality theatrics.

Against that backdrop, the Pax Silica tweet changes the subject. It pivots the frame from transactional market access—pulses, steel, GSP-like benefits—towards a deeper technology and supply-chain partnership. It tells Indian policymakers and markets that, despite the noise, Washington still sees India as integral to its long-term strategy on semiconductors, AI and critical minerals. It also implicitly acknowledges a shifting centre of gravity in the relationship: away from haggling over tariffs and towards co-designing the architecture of a new “silicon order”.

The technical angle: India in the silicon stack

Technically, Pax Silica is an attempt to build an integrated, “trusted” silicon and AI ecosystem spanning the entire stack—from critical mineral extraction and refining through wafer fabrication and chip design to cloud, data centres and AI compute. For India, whose semiconductor ambitions are still nascent and heavily dependent on state incentives, this is a chance to plug into the global value chain at multiple points, rather than merely as an assembly hub.

Three aspects stand out from an Indian technical perspective:

Ecosystem access: Pax Silica brings together players that control core bottlenecks: US design IP and EDA tools, Dutch lithography, Japanese and Korean speciality materials, and Israeli and Singaporean niche process capabilities. India will not acquire these overnight, but structured membership gives it a formal seat at the table where process nodes, standards and collaborative investments are discussed.

AI and compute infrastructure: The initiative is not limited to chips; it is explicitly about AI-ready infrastructure—high-performance computing, trusted cloud, secure under-sea cables, and data-centre standards. This aligns with India’s push for sovereign cloud and a national AI mission, both of which currently suffer from a lack of indigenous high-end compute and advanced silicon.

Standards and interoperability: Technical participation will inevitably involve adopting common standards on security, testing, and interoperability for hardware, firmware and networks. Over time, this can lift Indian industry practices up the value chain, but it will also force a more disciplined, audit-heavy culture across fabs, EMS firms and telecoms.

India’s own Semiconductor Mission

Delhi is also putting serious money on the table. India already operates an incentive architecture that, in effect, functions as a matching grant for domestic high-performance chip manufacturing—an open-ended, one-for-one logic in which the state stands ready to co-fund eligible capital expenditure alongside private investors. In addition, policy signalling around indigenous AI compute has begun to move beyond mere procurement towards manufacturing ambition: an outlay stated to be in excess of ₹50,000 crore has been floated to catalyse domestic GPU and GPU-class, high-performance chip manufacturing, with subsidy or subvention designed to match private commitments rupee-for-rupee. Read in this light, Pax Silica is not just an external invitation; it intersects with an Indian intent to move from renting high-end compute to making it—and to do so within a “trusted” ecosystem rather than at its margins.

The obligations are non-trivial. Indian manufacturers will have to manage higher compliance costs, traceability demands and security audits. A sharper line between “trusted” and “non-trusted” suppliers will, in practice, translate into progressive decoupling from Chinese equipment and components in sectors such as telecom, data centres and possibly even consumer electronics. That will require both capital and political will.

Geostrategic angle: technology as alignment

Geostrategically, Pax Silica is a response to two vulnerabilities: the geographic concentration of chip manufacturing in East Asia and China’s dominance in critical minerals and processing. The original group of countries involved are close US security partners in the Indo-Pacific and Europe, forming a loose “techno-bloc” designed to reduce Beijing’s leverage over the hardware foundations of the digital economy.

India’s inclusion carries several implications:

From swing state to system node: India moves from being treated as a “swing state” to being embedded—at least in the technology domain—in a US-led ecosystem. It becomes a necessary node in an alternative supply chain that needs both its domestic market and its manufacturing potential to be credible.

China signalling: Joining a US-led silicon architecture will be read in Beijing as a strategic choice, even if Delhi continues to insist on multi-alignment. It will likely invite some form of retaliation—subtle or otherwise—in sectors where India remains dependent on Chinese inputs, such as APIs in pharma, solar modules and certain electronics components.

Security entanglements: The more India’s critical infrastructure is built using Pax Silica-aligned hardware and standards, the more it will become integrated into broader US-led security and intelligence frameworks. Cyber incidents and supply-chain disruptions affecting Indian nodes will no longer be “national” events alone, but alliance-scale issues.

This does not mean India loses all strategic autonomy. It does, however, mean that in technology and supply-chain security, “alignment enough” with the West will become hard-wired through code, standards and capital flows. Multi-alignment will remain viable primarily in domains that are not deeply digitised or silicon-dependent.

Advantages for India: capital, capability, and clout

If managed well, the upside for India can be substantial.

Investment and jobs: Pax Silica membership can unlock and de-risk large semiconductor and advanced manufacturing investments in India by providing investors with a coherent framework of rules, protections and political backing. This complements New Delhi’s own incentive schemes and derisks projects against geopolitical shocks and export-control uncertainty.

Capability building: Structured cooperation in R&D, design, packaging and AI infrastructure can accelerate India’s climb up the value chain. Instead of trying to replicate every piece of the ecosystem indigenously, India can specialise where it has comparative advantages—design talent, software, system integration—while leveraging partners for capital-intensive or IP-heavy segments.

Negotiating leverage: Inside the club, India’s massive market and talent pool convert into bargaining power over standards, governance and deployment of new technologies. Outside, membership gives Delhi a stronger hand in discussions with the EU, ASEAN and the Global South, where it can present itself as a bridge between Western technology ecosystems and developing-country needs.

In political terms, Pax Silica also helps rebalance the narrative of the India–US economic relationship. Instead of being framed as a story of missed trade deals and tariff disputes, it can be presented domestically as a partnership in “future-proofing” India’s growth by securing access to the hardware and infrastructure of the 21st century. That is more saleable to an Indian public wary of asymmetric concessions in traditional trade.

Obligations and risks: the fine print

The benefits, however, come with obligations that Delhi cannot afford to gloss over.

Export-control alignment: Pax Silica is anchored in stringent export-control regimes designed to keep “countries of concern” away from advanced technologies. India will be expected to tighten its own export-control laws and practices in line with US and allied expectations, which will complicate its relations with Russia and further narrow the room for technology transactions with China.

Policy convergence in the digital realm: Technology alliances bleed into data and platform governance. Pressure will mount on India to harmonise elements of its data protection, cross-border data flows, encryption and platform regulation with the preferences of the US and other members. While not eliminating digital sovereignty, this will reduce the space for purely unilateral swings in regulatory posture.

Distributional impact at home: Compliance with security-driven supply-chain standards raises entry barriers. Large conglomerates and foreign majors will find it easier to absorb these costs than MSMEs, potentially entrenching concentration in high-tech segments. If not mitigated, this could exacerbate domestic inequalities within the electronics and digital economy.

IP and genuine transfer: Past experience with Western high-tech regimes shows that membership of a regime does not automatically translate into real technology transfer. Without hard-nosed negotiation, India may find itself hosting capital-intensive facilities that operate as enclaves, with limited diffusion of know-how into the broader ecosystem.

In short, the invitation is neither a free lunch nor a fait accompli. It is an opening offer in a negotiation that must be approached with clear red lines and concrete asks—on co-development, joint IP, localisation of high-end skills, and flexibility in dealing with other partners.

A silicon inflection in India–US ties

Seen in totality, the Ambassador’s tweet is less about social media and more about structure. It marks a shift from a narrow, tariff-centric view of trade to a broader understanding of economic security in which semiconductors, AI and critical minerals sit at the core. For India, accepting the invitation to Pax Silica on well-negotiated terms could accelerate its transition from a large digital consumer to a meaningful producer—and shaper—of the global technology order.

But it will also hard-wire new dependencies and constraints into India’s strategic and regulatory choices. The task for policymakers in Delhi is to convert this opening into a balanced compact: one that brings in capital, capability and clout without hollowing out strategic autonomy or domestic policy space. If that balance can be struck, this modest tweet—timestamped on a January evening—may, in retrospect, be remembered as a hinge moment in both India’s economic trajectory and its place in the emerging silicon geopolitics.