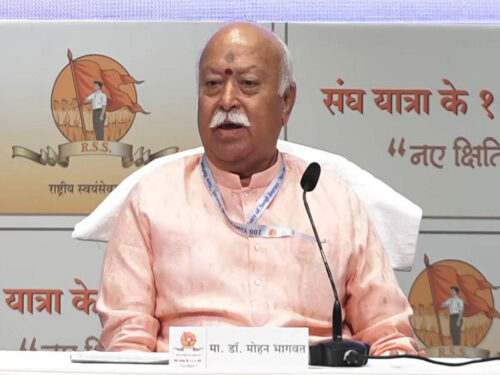

The forthcoming visit of Shri Mohan Bhagwat Ji, Sarsanghchalak of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, to Punjab on February 25–26, 2026, is very significant for the state. It carries hope. It carries opportunity. It also carries expectations.

The forthcoming visit of Shri Mohan Bhagwat Ji, Sarsanghchalak of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, to Punjab on February 25–26, 2026, is very significant for the state. It carries hope. It carries opportunity. It also carries expectations.

His decision to engage with ex-servicemen in Pathankot, interact with youth, and meet civic groups comes at a crucial juncture. He is not an ordinary public figure; his words carry weight and are closely watched across the political spectrum. In many ways, he is among the most influential leaders in India today. With the 2027 Punjab Vidhan Sabha elections gradually approaching, this visit assumes significance beyond routine organizational outreach. In Punjab, perception often shapes political reality, and therefore both tone and substance will matter.

For nearly 55 percent of Punjab’s electorate, who are Sikhs, the RSS and the BJP are not viewed as separate entities. They are perceived as part of one ideological framework. Whether that perception is entirely fair is open to debate. But it exists. And it shapes belief and voting behavior.

Punjab’s political psychology is layered. It carries unique historical wounds across centuries. Post-1947, a belief took root among sections of Sikh society that the RSS views Sikhism as part of a broader Hindu civilizational stream. Some interpret this as shared heritage. Others perceive it as gradual assimilation. The slogan “Panth khatre vich hai,” frequently raised during politically sensitive periods by panthic parties, has over time concretized this anxiety. What may have begun as electoral rhetoric hardened into collective suspicion. In villages, in diaspora circles, and in religious forums, this narrative continues.

It is important to underline that the unease is not social. Sikh and Hindu families in Punjab share language, culture, and kinship ties. Inter-community marriages are common. Social coexistence is natural. The discomfort is ideological, to a few.

The rupture deepened in 2020 with the introduction of the three farm laws by the government led by Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi Ji. Although the reforms were projected as long overdue structural changes in agriculture, Punjab perceived the move as unilateral. Farmers felt unheard. The narrative spread rapidly and uncontrollably. The year-long protests left emotional scars. Even after repeal, a sense of distance remained. There was also concern that moderate leadership during the agitation gradually gave way to harder voices, increasing polarization in an unprecedented manner, which was controlled by the Government with extreme sanity.

At the same time, it would be incomplete not to acknowledge the visible efforts made by the Government of India under Shri Narendra Modi Ji to reach out to Sikh sentiment. The opening of the Kartarpur Corridor fulfilled a long-pending aspiration of the Sikh community. National commemorations of Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji and the recognition of the Sahibzadas placed Sikh history prominently in India’s official narrative. These gestures were appreciated by many, including this writer. They conveyed respect, they conveyed acknowledgment. Yet gestures alone were insufficient to dissolve structural mistrust built over decades of propaganda. Trust requires clarity and sustained engagement.

In today’s climate, narratives travel faster than facts. Recently, I heard a podcast where a self-described “Sikh intellectual” suggested that ideologically Sikhism is closer to Islam. Such assertions, when amplified on social media, create confusion and deepen divides. Whether driven by ignorance, intentionally or mischievously, such narratives influence impressionable minds. Responsible leadership becomes even more essential in such times.

At the heart of Punjab’s anxiety lies a constitutional ambiguity. Article 25 of the Indian Constitution, through Explanation II, includes Sikhs—along with Jains and Buddhists—within a broader Hindu legal framework for limited purposes. Legal scholars have argued that this was administrative in intent. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar clarified during constitutional debates that it was not meant to erase identity. The Supreme Court of India has repeatedly recognized Sikhism as a distinct religion. Yet the wording remains unchanged. For many Sikhs, the clause symbolizes something larger. It feeds the perception of subsuming identity.

Former Chief Minister Parkash Singh Badal once burnt copies of the Article 25 provision in protest. Yet the issue is complex. Any constitutional change could carry implications for reservation safeguards extended to Scheduled Caste Sikhs. Theologically, Sikhism rejects caste hierarchy. Socially, caste realities persist. Therefore, the matter carries deep legal and social implications beyond symbolism. It requires thoughtful engagement. Even openness to dialogue on this subject would reassure many that their concerns are being heard.

In this context, Shri Mohan Bhagwat Ji’s recent remarks in Mumbai were significant. He clearly stated that Sikhism has its own religious traditions, maryadas, and panth, and that it is distinct as a religion. At the same time, he spoke of societal bonds and shared heritage. This reflected the lived reality of Punjabi society. Shared culture does not negate distinct faiths. However, many in Punjab would welcome even greater clarity in the same spirit during his visit here, so that interpretative ambiguity, psychological suspicion and paranoid may gradually fade.

No discussion in Punjab can bypass “1984” and the dark decade that followed. Operation Blue Star widely regarded by many as avoidable, poorly handled, and politically driven along with the anti-Sikh violence after the assassination of Smt. Indira Gandhi, left wounds that remain deeply personal. Justice has moved slowly, and for many, it feels incomplete.

In recent years, a new narrative has surfaced suggesting that the BJP compelled the then Congress government to carry out Operation Blue Star, based selectively on references from autobiography of its senior leader. Such interpretations risk overturning constitutional responsibility and distorting historical truth. Can decisions of that magnitude be forced on the government in power by any one, is any bodies guess work. The full truth deserves careful and balanced space. Punjab does not seek competitive political narratives. It seeks acknowledgment, honesty, and closure. An empathetic and historically grounded reference to this chapter during the visit could help soften hardened perceptions and encourage a healing discourse.

Recently, a friend returning from Canada after nearly a decade made a passing remark at Indira Gandhi International Airport. He wondered why the Delhi airport should not be named after Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji for his sacrifice for humanity. Won’t that be more appropriate? His comment surprised me. It had a deep meaning. It reflected how diaspora sentiment remains sensitive to symbolism connected with Sikh sacrifice and the 1984. Such impressions shape long-term attitudes.

There is also a delicate truth. Among a small section of Sikhs, though vocal, there exists quiet hostility toward what is perceived as a Hindutva political agenda. This hostility is neither universal nor dominant, but it is real. Social media amplifies anger. Hardline rhetoric from different sides fuels mistrust. These sentiments stem from accumulated impressions, fears of cultural homogenization, demographic rhetoric elsewhere, and political messaging that echoes in Punjab. Such concerns cannot simply be dismissed. They must be addressed through reassurance.

Punjab’s concerns today are practical as well as emotional. Youth migration continues at an alarming pace. Drug abuse remains a serious challenge. Law and order concerns persist. Agriculture faces economic stress. Water disputes remain unresolved. Chandigarh’s status continues to evoke sentiment. These issues shape voter behavior as much as identity does. With the Aam Aadmi Party facing governance criticism, Congress navigating internal turbulence, and the Shiromani Akali Dal carrying historical baggage, the BJP seeks space to expand. Yet expansion in Punjab requires humility, federal sensitivity, and visible partnership with rural Sikh constituencies.

The 2027 elections will not be decided by arithmetic alone. They will be shaped by emotion. The BJP’s vote share may have risen in certain urban pockets, but rural Sikh support remains limited. To grow meaningfully, the emotional barrier must be addressed first.

Shri Mohan Bhagwat Ji’s visit offers an opportunity. Clear and simple communication can make a difference. Reaffirming Sikhism’s full distinctness. Expressing openness to dialogue on constitutional ambiguities and their implications. Acknowledging Punjab’s sacrifices in nation-building and the Gurus’ sacrifices for religious freedom and human dignity.

Punjab does not reject unity. It resists dilution. Sikh identity and Indian identity have coexisted without contradiction. Recognition is not concession. It is respect.

This visit can be more than outreach. It can be reassurance. It can be a beginning.