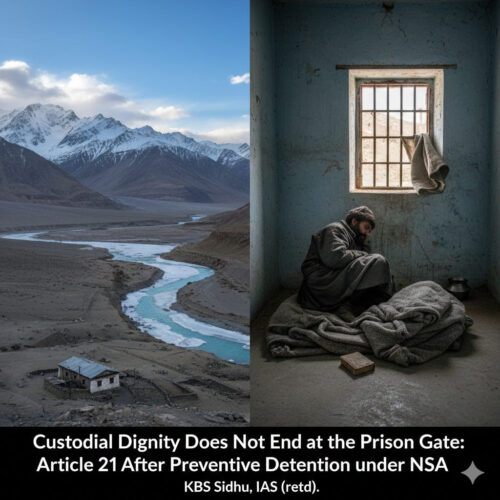

On Saturday evening, 7 February, a post on X by Dr Gitanjali J. Angmo—written shortly after she met Sonam Wangchuk in custody—cut through the day’s noise because it was not slogan but detail. She relayed his description of a bone-chilling winter spent in a stone-and-cement cell with several window openings covered only by iron bars, no shutters to stop wind, and no bed—only blankets on a cold concrete floor. He claimed the indoor temperature matched the outdoors, and that wind chill made sleep punishing. Whatever one’s view of the legality or necessity of his detention, this account raises a question that precedes politics: what does Article 21 demand of the State once it has taken custody of a human being?

On Saturday evening, 7 February, a post on X by Dr Gitanjali J. Angmo—written shortly after she met Sonam Wangchuk in custody—cut through the day’s noise because it was not slogan but detail. She relayed his description of a bone-chilling winter spent in a stone-and-cement cell with several window openings covered only by iron bars, no shutters to stop wind, and no bed—only blankets on a cold concrete floor. He claimed the indoor temperature matched the outdoors, and that wind chill made sleep punishing. Whatever one’s view of the legality or necessity of his detention, this account raises a question that precedes politics: what does Article 21 demand of the State once it has taken custody of a human being?

The Place Matters: Jodhpur’s High-Security Jail and Its Long Shadow

The particulars are not incidental. Wangchuk is lodged in a high-security jail in Jodhpur, Rajasthan, a facility designed for strict custody arrangements where ordinary assumptions of comfort often give way to institutional routine. The setting also carries a historical echo. After Operation Blue Star, Jodhpur became associated in public memory with prolonged preventive detentions: among those held there were persons arrested from around the Darbar Sahib complex, and accounts from that period describe detainees being kept for years, including under the National Security Act, without trial. One need not litigate history to absorb the constitutional lesson it leaves behind: when sub-human conditions of detention are normalised, the line between “lawful custody” and “quiet cruelty” becomes dangerously easy to blur.

Preventive Detention: Constitutional Permission, Not Constitutional Amnesia

Preventive detention occupies a deeply uncomfortable place in India’s constitutional architecture. It is one of the few instances where the Constitution, while guaranteeing fundamental rights, simultaneously enables their curtailment in the name of public order, security, or the interests of the State. The irony is plain: Article 22 explicitly contemplates preventive detention even as Articles 19 and 21 stand as the grammar of liberty in a constitutional democracy.

Unlike many fundamental rights that are confined to Indian citizens, the protective umbrella of Article 21 extends to all persons—citizens and foreigners alike. Yet the constitutional validity of preventive detention, repeatedly upheld by the Supreme Court, does not exhaust the inquiry. The legality of the detention order is only the starting point. What follows—the conditions of custody, the treatment of the detainee, and the preservation of human dignity—remains firmly governed by Article 21. The Constitution does not create a rights vacuum once a person crosses the prison threshold. If anything, the assumption of custody enlarges the State’s responsibility: when the State restrains liberty, it also assumes an inescapable duty of care.

Article 21 Continues in Custody

Indian constitutional jurisprudence has been unambiguous for decades: prisoners and detainees do not shed fundamental rights at the prison gate. Article 21, understood as a guarantee of life with dignity, applies to an undertrial, a convict, and a preventive detainee alike, subject only to restrictions that are just, fair, and reasonable. A lawful confinement is not a licence for indignity; it is a legal status that triggers enforceable constitutional obligations.

This is why the consequential part of any detention is not merely the order, but the process thereafter. Courts may scrutinise the legality of detention at the entry point, but Article 21 polices what the State does after entry—how it houses, feeds, protects, and treats the person it has rendered wholly dependent.

When Neglect Becomes a Rights Violation

The account from custody, as relayed in the tweet, speaks of a cell where strong winds pass through multiple openings, and the detainee is left to sleep without a mattress or bed, blankets spread on a cold concrete floor. These are not allegations of custodial violence. That, paradoxically, is precisely what makes them constitutionally instructive. They suggest neglect, indifference, and institutional inertia—conditions that quietly erode dignity without leaving visible scars.

The State’s obligation under Article 21 is not limited to preventing physical abuse. It extends to ensuring basic human needs: warmth, shelter, rest, sanitation, and reasonable comfort consistent with human dignity. The idea that a detainee must simply “bear” whatever the institution happens to provide is incompatible with the Supreme Court’s reading of “procedure established by law” as a substantive guarantee, not a formal ritual. The process must be humane in substance, not merely lawful in form. Preventive detention may authorise custody; it does not authorise humiliation by default.

Custody Transfers Power—and With It, Responsibility

Many constitutional debates on preventive detention focus on legality: whether grounds were communicated in time, whether representation was considered, whether advisory board procedures were complied with. These safeguards matter; they restrain executive power at the entry point. But they do not address the lived reality thereafter. Article 21 operates continuously. It governs the quality of life in custody, not merely the legality of entry into it.

This continuity matters because the detainee’s vulnerability is total. A free citizen can add blankets, seal windows, purchase a heater, or shift rooms. A detainee cannot. In constitutional terms, custody transfers the practical ability to secure basic needs from the individual to the State. The duty of care therefore becomes not merely moral but structural: the State must do what it has disabled the detainee from doing for himself. That is why custodial conditions are not administrative footnotes; they are constitutional compliance.

The Civic Meaning of Innovation Behind Bars

The tweet contains another striking element: rather than only protesting discomfort, Wangchuk is said to have proposed a no-cost, zero-carbon floor-heating solution using relatively warm borewell water, with the added possibility of cooling in summer—an idea he wishes to test across prison barracks. He seeks only basic instruments such as thermometers and permission from the authorities or the court to work on the idea.

This detail transforms the narrative from a personal grievance into a public-interest proposition. It underscores a missed opportunity for the prison administration: to treat the detainee not as a problem to be managed but as a citizen, even in custody, capable of contributing to the improvement of custodial life for others. It also points to an ethical truth: the easiest way to preserve order is to reduce a detainee to passivity; the harder, more constitutional path is to preserve order without crushing personhood.

Constitutional Minimums and Civilisational Standards

International human rights standards, frequently used by Indian courts as interpretive aids, reinforce the constitutional logic that dignity is not a reward for good behaviour or correct opinions; it is an attribute of personhood. The baseline requirements of adequate accommodation, protection against climatic extremes, and respect for inherent dignity are not luxuries. They are the minimum that separates custody under law from custody under impulse.

None of this requires adjudicating the merits of the detention. One may believe a detention to be lawful, justified, even necessary—and still insist that custodial conditions meet constitutional standards. This is not a contradiction. It is the essence of a rights-based constitutional order. The rule of law is not merely the State’s ability to restrain; it is the State’s willingness to restrain itself while restraining others.