Union Budget 2026–27 presents itself as a step along the path of fiscal consolidation—lower deficits, a clearer medium-term anchor, and continued emphasis on capital expenditure. Yet beneath the headline numbers lies a structural constraint that deserves more attention than it typically receives in post-budget commentary: the debt servicing burden, especially interest payments, is consuming a scale of resources that materially compresses fiscal choice.

Union Budget 2026–27 presents itself as a step along the path of fiscal consolidation—lower deficits, a clearer medium-term anchor, and continued emphasis on capital expenditure. Yet beneath the headline numbers lies a structural constraint that deserves more attention than it typically receives in post-budget commentary: the debt servicing burden, especially interest payments, is consuming a scale of resources that materially compresses fiscal choice.

The One Number That Explains the Squeeze

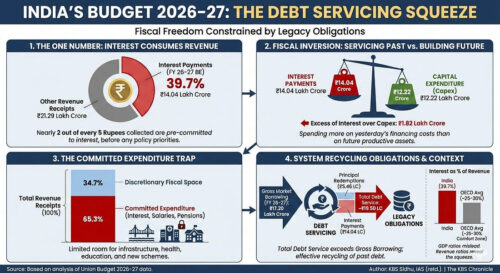

The single most telling number in the Budget arithmetic is this: interest payments are budgeted at Rs 14.04 lakh crore in FY 2026–27 (BE), absorbing 39.7% of total revenue receipts of Rs 35.33 lakh crore. Put plainly, nearly two out of every five rupees that the Government of India expects to collect in revenue are pre-committed to interest before the first rupee can be deployed for policy priorities—whether infrastructure, health, education, defence modernisation, climate adaptation, or social protection.

This is not an abstract bookkeeping ratio. It is a measure of fiscal freedom. When interest consumes such a large share of revenue, the Budget becomes less an instrument of democratic choice and more a framework for meeting legacy obligations. The state can still spend, of course—but the space for discretionary spending increasingly depends on either (a) compressing other expenditures, (b) raising revenues faster than commitments, or (c) borrowing more, which then enlarges future interest burdens. The Budget thus reveals an uncomfortable but unavoidable truth: fiscal capacity is increasingly constrained by the arithmetic of past borrowing.

The Fiscal Inversion: Servicing the Past More Than Building the Future

A second number reinforces the gravity of the moment. Interest payments (Rs 14.04 lakh crore) now exceed capital expenditure (Rs 12.22 lakh crore) by Rs 1.82 lakh crore. This inversion is more than symbolic. Capital expenditure—roads, railways, ports, irrigation, energy infrastructure, and public assets—represents the state’s investment in future productive capacity. Interest payments represent the cost of yesterday’s financing. When interest outgo is larger than public capital formation, the Budget signals that the system is devoting more fiscal energy to servicing the past than to building the future.

The Budget does continue to prioritise capital expenditure, and capex rises in nominal terms. But the deeper issue is relative pressure: even after a rise, capex remains constrained while interest grows as a committed, non-negotiable item. This is the classic crowding-out dynamic—not necessarily in the narrow “government borrowing crowds out private investment” sense alone, but in a broader fiscal sense: committed debt service crowds out developmental and investment expenditure.

Borrowing and Redemptions: A System Recycling Obligations

This stress becomes sharper when viewed through the lens of financing flows. The government’s gross market borrowing programme for FY 2026–27 is budgeted at Rs 17.20 lakh crore, with redemptions (principal repayment) at Rs 5.46 lakh crore. If one adds interest payments to principal redemptions, total debt servicing comes to roughly Rs 19.50 lakh crore—a figure that is larger than gross market borrowing itself. The implication is straightforward: a very substantial portion of annual financing is effectively recycling through the system to meet legacy obligations. Borrowing is not merely funding fresh development outlays; it is also financing the costs of existing debt.

This is where the concept of “fiscal consolidation” can become misleading if interpreted narrowly. A deficit may reduce at the margin, and debt-to-GDP ratios may glide down in projections, but the lived fiscal reality is shaped by rigidities. The Budget’s stress is not only the headline fiscal deficit; it is the structural rigidity of expenditure.

The Committed Expenditure Trap: Why Fiscal Space Feels Smaller Every Year

The clearest expression of that rigidity is the “committed expenditure trap”—where interest, salaries, and pensions absorb roughly 65.3% of revenue receipts, leaving only 34.7% as discretionary fiscal space for everything else the state is expected to do. When two-thirds of revenue is spoken for before policy choices begin, the Budget’s scope for reallocation, innovation, and expansion of priority spending becomes limited.

This matters because India’s ambitions are large and legitimate: infrastructure scale-up, manufacturing competitiveness, jobs, human capital investment, and climate resilience. These ambitions require sustained spending—especially growth-enhancing public investment and high-quality social expenditure. Yet the Budget arithmetic indicates that fiscal room is narrowing.

The Next Pressure Point: The Pay Commission Cycle

And it may narrow further. One identifiable pressure point is the 8th Pay Commission cycle, which could materially raise salary and pension burdens from FY 2027–28 / FY 2028 onwards, intensifying the same compression of discretionary space that already exists. Whether or not one agrees with the merits of such revisions, the fiscal reality is that pay and pension hikes arrive as structural increments to committed expenditure—exactly the category that is hardest to compress later.

Debt Sustainability Depends on Growth Staying Ahead of Interest

The government’s stated strategy increasingly emphasises a debt-to-GDP anchor—55.6% in FY 2026–27 on a medium-term glide path. In principle, shifting toward a debt anchor can be sensible. But the success of such a trajectory depends heavily on a single macroeconomic condition: nominal GDP growth must remain strong enough to outpace the effective interest cost on government debt.

When the interest rate–growth differential is favourable, debt ratios can stabilise or decline even with moderate deficits. But the buffer is not guaranteed. If growth slows or yields harden, the arithmetic changes quickly—and interest burdens rise further, creating a feedback loop that compresses fiscal space.

Market Absorption and the Interest Feedback Loop

This is also why record borrowing levels raise a market absorption question. Even if the debt-to-GDP ratio eases marginally, gross borrowing at large scale can strain domestic bond-market absorption, especially when combined with state borrowings. If yields remain elevated, the interest bill compounds. Over time, this can produce exactly the kind of self-reinforcing stress that policymakers seek to avoid: more interest requires more borrowing or more compression elsewhere, which can reduce growth-supportive spending, which can in turn weaken growth.

International Comparison: GDP Ratios Mislead, Revenue Ratios Reveal

International comparisons can be misleading if they focus only on interest as a share of GDP. India’s interest burden—about 3.6% of GDP—sits within an emerging-market range and is only modestly above the OECD average cited for 2024 (around 3.3%). The sharper and more revealing indicator is interest as a share of revenue: at 39.7%, India appears well beyond the comfort zones commonly referenced in fiscal sustainability discussions, where 25–30% is often associated with meaningful crowding out.

Where This Leaves Fiscal Policy

The point is not to declare inevitability or crisis for dramatic effect. It is to recognise the constraint. A Budget can promise many things, but the state’s ability to deliver depends on fiscal space—and fiscal space depends on the structure of committed expenditure. The numbers in Budget 2026–27 show that debt servicing is not a peripheral issue; it is central to the country’s policy capacity.

Note on Sources: Full PDF Report Linked Separately

For readers who want the underlying calculations, the charts, and the full set of sources and references, I am providing a link to my detailed PDF research report. That report is intended for academic policy researchers, serious financial journalists, and students of finance and economics who want to verify the arithmetic and trace the primary materials in depth.

This summary, by design, presents the core story: interest now pre-empts the exchequer at scale, and fiscal sustainability is increasingly about reclaiming discretionary space rather than merely managing headline deficit targets.