There is intense anxiety today in India’s agricultural sector. The recent India–United States trade deal has revived an old fear: that Indian farmers will be exposed to subsidised foreign produce, domestic prices will crash, and livelihoods will suffer. The concern is understandable. But the real question is this: is the trade deal the real threat to Indian farmers, or is it merely exposing long-standing weaknesses created by India’s own domestic policies?

There is intense anxiety today in India’s agricultural sector. The recent India–United States trade deal has revived an old fear: that Indian farmers will be exposed to subsidised foreign produce, domestic prices will crash, and livelihoods will suffer. The concern is understandable. But the real question is this: is the trade deal the real threat to Indian farmers, or is it merely exposing long-standing weaknesses created by India’s own domestic policies?

A closer examination of global farm support, trade data, and India’s internal policy framework suggests a clear answer. The greater danger to Indian agriculture lies not in trade agreements, but in the way Indian farm policy itself is designed and implemented. That is where reforms are required and farm sector needs to be liberalised. Probably the three farm laws could have been a small start in that direction.

U.S. Farmers Are Protected; Indian Farmers Are Not

In the United States, agriculture is treated as a strategic sector deserving protection from market shocks. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), U.S. farmers received positive producer support averaging about 7% of gross farm receipts during 2022–24.

This support is institutional and predictable. It includes direct income payments, heavily subsidised crop insurance, disaster relief, and counter-cyclical support that activates automatically when prices fall or markets are disrupted. These measures ensure that American farmers are not left to absorb global volatility on their own.

The OECD notes:

“Four economies — China, Japan, the European Union, and the United States — accounted for roughly 69% of all positive producer support in 2022–24.”

(OECD, Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2025

https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/agricultural-policy-monitoring-and-evaluation-2025_a80ac398-en/full-report.html)

Simply put, the U.S. state stands behind its farmers.

India’s Policies Implicitly Tax Farmers

India’s policy framework operates in the opposite direction. The OECD’s assessment is unusually blunt. For 2022–24, India’s Producer Support Estimate (PSE) averaged –14.5% of gross farm receipts, the lowest among major economies.

The OECD states:

“India has the most negative Producer Support Estimate (PSE) of all the countries covered in this report… domestic producers have been implicitly taxed, as budgetary payments to farmers do not offset the price-depressing effect of complex domestic marketing regulations and trade policy measures.”

(OECD, India Country Chapter

https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2025/10/agricultural-policy-monitoring-and-evaluation-2025_354e7040/full-report/india_a08610a6.html)

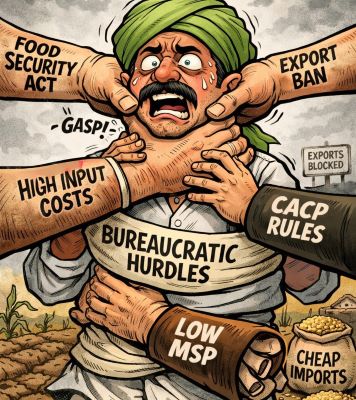

This negative support is not accidental. It is the outcome of a policy architecture where:

Food inflation control overrides farmer income

Export bans are imposed abruptly

Domestic prices are kept below global levels

The OECD further observes:

“Policies reducing domestic prices gave rise to USD 179 billion in implicit taxation in 2022–24, while benefiting consumers, these also have a distorting effect on producers.”

(OECD Overview

https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/agricultural-policy-monitoring-and-evaluation-2025_a80ac398-en/full-report/overview-of-agricultural-policies-and-support_68470b91.html)

Translated into Indian terms, this amounts to nearly ₹2 lakh crore of income foregone annually by farmers.

Sharad Joshi led “Task force on agriculture” said the same thing much earlier in 2004. Bhupinder Singh Mann, in Rajya Sabha, in 1993 was able to make the then Finance Minister admit on the floor of the house that the Indian farmers are subjected to an negative aggregate measure of support to the tune of 72% of the gross production.

Food Security and Procurement Policies Work Against Farmers

This distortion is reinforced by India’s own statutory and institutional arrangements.

The National Food Security Act, while vital for consumer welfare, has effectively converted farmers into instruments of cheap food policy. Procurement priorities focus on stocking grain at the lowest possible price rather than ensuring remunerative returns to producers.

Similarly, the Terms of Reference of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) are heavily weighted towards:

Consumer price stability

Fiscal considerations

Availability of foodgrains

Farmer profitability is treated as a secondary concern. MSP calculations may reference costs, but procurement is neither universal nor assured, leaving most farmers exposed to open-market price suppression.

Export Bans and Import Openings: A Repeated Policy Pattern

Perhaps the most damaging feature of Indian farm policy is its knee-jerk nature.

Whenever domestic prices rise:

Exports are banned overnight (wheat, rice, onions, sugar)

Imports are suddenly liberalised

Duties are cut to cool prices

These measures may provide short-term consumer relief, but they destroy price signals, discourage investment, and penalise farmers who respond to market demand. No other major agricultural economy treats its farmers with such policy unpredictability.

India Is a Net Agricultural Exporter to the U.S.

Against this backdrop, fears of being overwhelmed by U.S. agriculture appear overstated.

India is a net exporter of agricultural and food products to the United States. In 2025 (January–November):

U.S. agricultural exports to India: ~$2.85 billion

U.S. agricultural imports from India: ~$5.9 billion

India exports high-value, labour-intensive products where it is globally competitive: basmati rice, spices, tea, coffee, processed foods, and marine products. There is no significant import of U.S. wheat, rice, or dairy, and safeguards on sensitive sectors remain intact even under the new trade arrangement.

What Indian Farmers Should Really Worry About

The evidence leads to a clear conclusion.

Indian farmers are not facing their greatest risk from trade deals. They are facing it from:

Price-suppressing domestic policies

Export restrictions used as inflation tools

Procurement systems skewed against producers

Institutional frameworks that prioritise consumers over cultivators

Trade agreements merely expose these vulnerabilities; they do not create them.

Conclusion

There is no denying the anxiety in the farm sector. But fear must be directed at the right target.

U.S. farmers are protected by policy.

Indian farmers are penalised by policy.

India exports more farm produce to the U.S. than it imports.

Until India reforms its food security framework, procurement policy, CACP mandate, and its reflexive use of export bans and import liberalisation, no trade deal will ever feel safe to farmers.