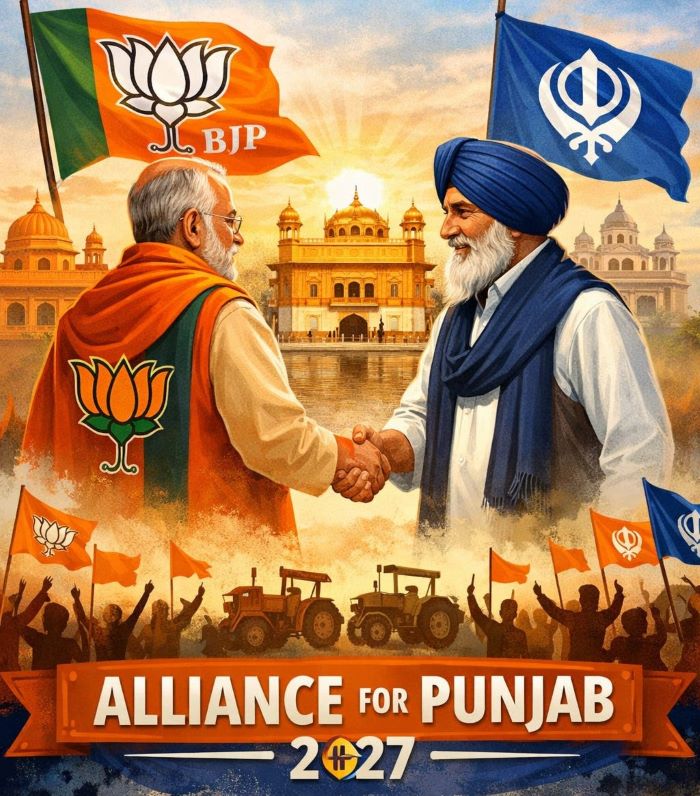

Punjab’s politics cannot be decoded through numbers alone. It is shaped by memory, identity, dignity, and acceptance. This is where the Bharatiya Janata Party continues to falter in Punjab—and why an alliance with a Panthic regional force like the Shiromani Akali Dal Punar Surjeet Akali Dal is not merely electorally prudent but socially unavoidable.

Punjab’s politics cannot be decoded through numbers alone. It is shaped by memory, identity, dignity, and acceptance. This is where the Bharatiya Janata Party continues to falter in Punjab—and why an alliance with a Panthic regional force like the Shiromani Akali Dal Punar Surjeet Akali Dal is not merely electorally prudent but socially unavoidable.

The BJP remains, by its support base and organisational DNA, an urban party in Punjab. Its strength lies in cities and towns, largely among Hindu voters. Rural Punjab—where Sikhs form an overwhelming majority and where political mood is set in villages rather than studios—continues to view the BJP with deep suspicion. This alienation may not always be rooted in facts, but politics runs on perception, not balance sheets.

The party has also shown a tendency to reopen old wounds through repeated irritants. The 2020–21 farmer agitation, which many—including myself—believe was built on a false and exaggerated narrative, nonetheless left deep scars. For rural Sikhs, the episode reinforced the idea that the BJP does not understand Punjab, even if it governs India.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has made visible and sustained efforts to bridge this gap—most notably through the Kartarpur Sahib Corridor and by giving national and international recognition to the martyrdom of Guru Tegh Bahadur and the supreme sacrifices of the Sahibzadas. Most recently, Amit Shah’s speech yesterday on the sacrifice of Guru Tegh Bahadur and the Sahibzadas was deeply emotional, marked by sincerity and genuine gratitude. It acknowledged, in unambiguous terms, the foundational role played by the Sikh Gurus in shaping India’s civilisational ethos and moral strength.

These were important gestures. But gestures alone do not translate into acceptance. Punjab demands something deeper: psychological legitimacy.

This is the missing link in the BJP’s Punjab strategy.

Electoral legitimacy is about numbers—winning seats, forming governments. Psychological legitimacy is about acceptance—whether people feel the government is theirs, whether they see it as organic or imposed. In Punjab, where Sikhs are in a clear majority and political consciousness is historically sharp, psychological legitimacy is not optional. It is decisive.

Nationally, the BJP has demonstrated that governments can be formed without majority vote shares. In 2024, it returned to power with about 36.5% of the national vote. But Punjab is not a laboratory for electoral engineering. In the 2024 Lok Sabha elections in Punjab, the BJP polled around 18.5%—its best ever solo performance—yet won zero seats, despite leading in over 30 Assembly segments. The Shiromani Akali Dal polled around 13.4%. Together, they crossed 31%, comfortably ahead of Congress and AAP individually. Still, division ensured defeat.

The lesson is clear: in Punjab, vote share without legitimacy produces power without acceptance—and that is politically unsustainable.

If the BJP were to form a government through fragmented mandates in a four-cornered contest, large sections of Sikhs would see it as an imposed arrangement. Punjab’s history shows that when political power lacks social acceptance, resistance follows—not always immediately, but inevitably. This is not alarmism; it is lived experience.

This is precisely why a Panthic alliance partner acts as a pressure-release valve. Like the safety valve in a pressure cooker, it allows dissent, emotion, and identity anxieties to dissipate safely. Without such a valve, pressure builds silently, and explodes unpredictably.

The political context ahead of 2027 makes this even more critical. The sacrilege issue, once electorally potent, is visibly fading. Repetition has diluted its force. The emerging agenda is law and order—gang violence, extortion, drugs, policing failures, and everyday insecurity. This is an area where the BJP believes it has narrative strength. But strength without acceptance will not translate into stability.

The BJP is also attempting to expand through deras, recognising their influence in rural Punjab. This is a tactical move—but spiritual influence cannot replace political legitimacy. Deras may mobilise votes, but they cannot absorb the social pressure that comes with governance.

Urban voters, too, are pragmatic. If the BJP appears isolated and non-viable, many will drift toward Congress or AAP. Punjab’s voters back winners, but they also reject governments that feel disconnected from their identity.

An alliance with SAD or other Akali Dal therefore serves two purposes: it consolidates votes and confers legitimacy. It reassures Sikhs that power is shared, not imposed. It allows governance to focus on real issues—jobs, drugs, security—instead of identity anxiety.

The BJP must, of course, negotiate firmly for seats. But more importantly, it must recognise this truth: in Punjab, electoral legitimacy without psychological legitimacy is fragile, temporary, and dangerous.