Infosys wants India to see it as a modern technology enterprise—an institution that rode the software-services wave and is now “moving up” into digital, platforms and artificial intelligence. Yet the public record increasingly tells a second story: a company that has quietly treated land as a parallel balance-sheet strategy—accumulating large parcels facilitated by the state’s industrial land machinery, sitting on them for years, and then cashing out when Bengaluru’s urban sprawl turns yesterday’s “industrial” acreage into tomorrow’s residential gold.

Infosys wants India to see it as a modern technology enterprise—an institution that rode the software-services wave and is now “moving up” into digital, platforms and artificial intelligence. Yet the public record increasingly tells a second story: a company that has quietly treated land as a parallel balance-sheet strategy—accumulating large parcels facilitated by the state’s industrial land machinery, sitting on them for years, and then cashing out when Bengaluru’s urban sprawl turns yesterday’s “industrial” acreage into tomorrow’s residential gold.

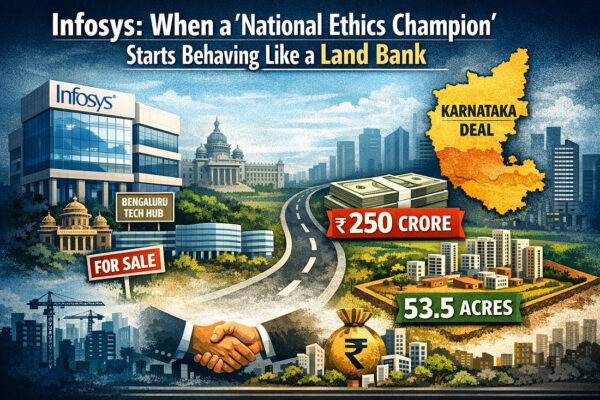

That contradiction has become impossible to ignore after the December 23 land deal in which Infosys sold 53.5 acres in the Attibele belt to real-estate developer Puravankara for ₹250 crore. Puravankara has signalled a residential ambition for the parcel—an expansive, high-density development with multi-million square feet of saleable area and a valuation logic that runs into several thousand crores. If you are truly a product-and-AI company, why does the arithmetic of your “non-core asset” sale look so much like a real-estate pipeline feeding a developer’s township machine?

The moral problem is not a land sale. It is the origin story of that land.

Karnataka’s industrial land ecosystem exists because the state claims a public purpose: land is aggregated and made available to industry to catalyse jobs, skills, exports and technology spillovers. That is the social bargain behind concessional rates, facilitated acquisition, and the entire logic of “industrial area” development. The bargain collapses the moment industrial land begins to resemble a long-dated option for private capital gains.

Infosys has historically been among the biggest beneficiaries of this ecosystem. Its own past disclosures and widely reported land acquisitions in and around Bengaluru show a scale of holdings that goes well beyond the needs of a single campus. For years, public commentary has asked why a software services company—especially one that claims to be graduating into higher-value products—needs to behave like a long-horizon land aggregator. The Attibele sale brings that question roaring back, because nothing about a residential developer’s business model is consistent with the public-purpose justification that underpins industrial land policy.

If the land was obtained through a public agency ecosystem built to promote IT, then a transaction that ends with a residential township is not merely a commercial decision—it is a breach of the social contract. And if the land was not obtained through such mechanisms, the company should remove doubt by making its full acquisition history and covenants public. Silence, in a matter like this, does not look like compliance; it looks like concealment.

Karnataka itself has acknowledged the abuse risk—yet enforcement remains an empty threat

Karnataka has repeatedly spoken about keeping industrial land for industrial use, and about curbing diversion and speculation. That rhetoric exists precisely because the state has seen how easily “industrial” parcels can be warehoused and later monetised once the surrounding city grows, roads expand, and metro corridors and ring roads turn the area into a residential hotspot.

But policy statements do not matter if enforcement is weak, timelines are ignored, and resumptions are rare. When institutions cannot or will not police utilisation, the state becomes an accessory to land-banking: it helps create the conditions for “industrial allotment today, residential conversion tomorrow.” Over time, this hollows out the credibility of the entire industrial development narrative.

The hypocrisy problem: preaching 70 hours, profiting from unearned urban appreciation

This story lands squarely on Narayana Murthy because he has chosen to act not merely as a founder but as a national moraliser. His sermon that young Indians should work 70 hours a week was framed as patriotism, productivity, and nation-building. It implicitly demanded sacrifice from labour.

Yet the Attibele episode symbolises something else: in India’s political economy, fortunes can be compounded not only by innovation but by sitting on land while the city does the work. This is not productivity; it is rent extraction—sometimes entirely legal, but still ethically indefensible when the original justification was employment-led technology development.

That is why the juxtaposition is so corrosive. A young engineer is lectured about longer hours and national duty, while the company’s capital gains story can be written without mentioning a single line of code: acquire, hold, appreciate, exit. If that is the model, then “70 hours” is not a development strategy; it is a convenient moral shield for an unequal system in which labour is asked to bleed while capital quietly harvests.

The family optics: tax-minimisation controversy and the right to lecture

The ethical discomfort deepens when one remembers that a significant shareholder in the Infosys story—Akshata Murty, daughter of N. R. Narayana Murthy and wife of former UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak—has been at the centre of international controversy over tax status and tax-minimisation narratives. For a period, she was reported to have claimed UK “non-domiciled”/non-resident-style tax treatment, relying on her foreign domicile and Indian citizenship, a status that attracted fierce political and public scrutiny in Britain because it could lawfully limit UK tax on overseas income unless remitted. This is not to allege illegality. It is to underline a plain truth: those who benefit from sophisticated, legally engineered advantage—whether through tax status, global residency rules, or the compounding of asset appreciation—carry reduced moral authority when they lecture ordinary young Indians about sacrifice, self-denial, and 70-hour devotion to the nation.

A simple transparency test Infosys should pass—if it truly has nothing to hide

If Infosys wants to be seen as an ethical technology major rather than a sophisticated land trader, it should voluntarily put the following on record for the Attibele parcel:

Exactly how the land was acquired (public allotment, consent acquisition, open market, or any hybrid route), with the chain of title.

The covenants attached to the land—use restrictions, alienation conditions, timelines, and penalties.

A utilisation history: what was proposed, what was approved, what was built (if anything), what was abandoned, and why.

All conversion, zoning, and development approvals tied to the buyer’s intended use.

Any premium, clawback, or value-capture paid back to the public exchequer in recognition of policy-driven appreciation.

If the company refuses to do this, then it has effectively chosen opacity—and opacity is a confession of how it expects the public to be treated: as spectators, not stakeholders.

What other states are doing about idle industrial land—and why Karnataka must stop looking away

Across India, governments are increasingly acknowledging that idle industrial land is a public-policy failure, not a private asset-management choice. Some have experimented with reclamation drives, structured surrender schemes, and rules designed to bring unutilised plots back into productive circulation. The point is not that every model is perfect. The point is that at least some governments have accepted the principle that industrial land is a scarce public resource, not a speculative chip.

Karnataka, which pioneered India’s IT ascent, should be the last state to tolerate the slow conversion of “industrial vision” into “residential monetisation.”

Conclusion: Infosys’s land story is a test of India’s governance spine

Infosys still has a choice. It can be the company that discloses, explains, and submits itself to the same accountability it prescribes to young employees. Or it can continue down the quieter path—where the most reliable product is not software, not AI, but real estate upside.

And now the unavoidable final indictment: the Government of Karnataka and its instrumentalities—particularly the agencies and planning authorities entrusted with industrial land—have behaved like Kumbhkaran, asleep while daylight robbery unfolds. Prime land that should have been ring-fenced for employment-generating technology capacity is instead allowed to be bartered into private colonisation—handed to township builders as if “industrial development” was merely a pretext and not a promise. If public-purpose land can lie idle for years and then quietly exit into residential profiteering at rates that appear grossly undervalued relative to downstream development potential, then Karnataka is not governing; it is enabling.

The state cannot keep preaching “investment, innovation, jobs” while its own land institutions look away when those very lands are converted into speculative estates. Either Karnataka wakes up, audits every such parcel, and enforces clawbacks and resumptions with real consequences—or it should stop pretending that its industrial land policy is anything more than a subsidy pipeline for the well-connected.